![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Flash in the Deadpan

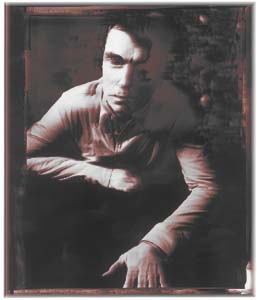

Still Byrne-ing: Years after the demise of the Talking Heads, David Byrne remains in the limelight. Photo by Danny Clinch

David Byrne's finely honed sense of irony survives undimmed on 'Feelings' album By Gina Arnold IN THE SLEW of recent books and television specials about the history of punk rock, none has failed to mention the crucial place of David Byrne's first band, the Talking Heads. Although the MC5, the New York Dolls, the Ramones, Iggy and the Pistols are more beloved, the Talking Heads were, in a way, far more seminal to the genre's development. For one thing, the band's initial makeup--upper-class students at RISD (The Rhode Island School of Design)--mimics the makeup of every subsequent American indie-rock band, whose members are usually drawn from overeducated Caucasian circles. But more importantly, the Talking Heads' 1977 song "Psycho Killer" was pretty much the first "punk-rock" thing most Americans ever heard, while 1978's "Take Me to the River" (the band's first real hit) and 1980's remarkable Remain in Light showed off the heretofore unsuspected range and mission of the genre. On the tour for Remain in Light, the band added high-caliber musicians like Nona Hendryx, Adrian Belew and Bernie Worrell to prove once and for all that punk rock was a truly musical and artistic endeavor--and would be ever after. Technically, the Talking Heads only broke up in 1991, but its members had all been working solo for years, their contributions ranging from the Tom Tom Club's influential rap track "Genius of Love" (covered now by Mariah Carey) to David Byrne's seminal electronica found-music work with Brian Eno, My Life in the Bush of Ghosts, and his world-music-oriented record label, Luaka Bop. And yet, despite the vast number of Talking Heads contributions, the popular reputation of leader David Byrne has suffered a severe decline since 1986, the year he graced the cover of Time magazine and put out a movie titled True Stories, which focused only half seriously on American eccentrics. To be sure, in one sense Byrne's career has flourished, on albums, at art exhibits (he's a photographer) and on various collaborations, including music for dance and opera: The Catherine Wheel and Music for the Knee Plays, a classically based orchestral piece titled The Forest and a soundtrack to the film The Last Emperor, for which, along with collaborator Ryuichi Sakamoto, he won an Oscar. But in another, broader way, the popular esteem Byrne once enjoyed has dissolved, and not merely because as a solo artist, Byrne does not write hits. The same is true of artists like Sinead O'Connor, Elvis Costello, even Paul McCartney, but they are still revered for their talent. Certainly, Byrne is not less talented than these prestigious artists. Unlike them, however, Byrne has always had a deliberately annoying persona, one which somehow suited the mood of the early '80s, but which, by 1995, had worn rather thin. BYRNE'S POSE--the one upon which the movie True Stories is essentially based--is that of a very detached sort of alien observing American culture, and this is an attitude which even in this day and age of irony-overload can be quite taxing to the observed. In fact, Byrne himself could be considered the Typhoid Mary of the Irony Epidemic, and that's not necessarily a good thing. Moreover, Byrne has always represented himself as a bit of a nervous case, and the result is that he makes those around him nervous. In 1988, a friend and I went to the New Orleans Jazz Festival, and wherever we went--junk stores in the French Quarter, obscure restaurants outside of the Quarter and, inevitably, a Neville Brothers show at Tipitina's--Byrne would show up too. Finally, we caught a glimpse of him behind a rack of voodoo dolls at a souvenir shop, and my friend actually stomped up, tapped him on the shoulder and said, "Mr. Byrne, could you please stop following us around?" That was, admittedly, an extreme (and rather rude) reaction to what was quite a coincidental situation. But even when not physically present, Byrne has often managed to create a prevailing sense that We Are Being Watched--by him, that is--and that our antics may be used at a latter date. It's not a pleasant feeling, which may be why he has been accused in the past of a kind of patronizing colonialization of musical styles. Like Andy Warhol, whose art often seemed subsumed in other people's ideas, Byrne is an artist whose main attribute is his point of view. To begin with, that point of view--the one elucidated in songs like "Psycho Killer" and particularly "Life During Wartime"--was refreshing and relevant. A recent special on punk rock, for example, made the observation that many of punk's earliest American progenitors--Richard Hell, the Ramones, Patti Smith and the Talking Heads--all took as their primary subject the idea of urban decay, specifically the declining urban and moral landscape of New York City. This is undoubtedly true of Talking Heads work like More Songs About Buildings and Food and Fear of Music, but it occurs to me now that Byrne's own artistic decline has, in a way, paralleled that of New York City itself. Back in the '80s, after literally decades during which the artistically inclined young people of every state of the union were drawn magnetically to Manhattan, music fans began to look outward--to music made by kids in Georgia, Minneapolis and Austin. Simultaneously, the cultural center of the world moved west, to Seattle, Tokyo and Hong Kong. And just as the Big Apple ceased to dominate America's imagination, so too did the insular New York-is-the-center-of-the-universe viewpoint of New York artists like Byrne and others (Laurie Anderson, Woody Allen and Julian Schnabel all come to mind) cease to beguile those of us "in the provinces" so to speak. Of course, in a way, Byrne himself was the first to notice this trend: as far back as 1981, he too began drawing on diverse musical sources--particularly the indigenous rhythms of Brazil, Japan and Africa. But for all Byrne's eclectic international perspective, his lyrics have remained firmly exclusionary, and those on his most recent album, Feelings (Warner Bros.), are no exception. As he has been ever since Remain in Light, Byrne is admirably fixated with rhythms. He sets off all his songs with beautifully crafted textures. Like 1992's Uh-Oh and 1994's David Byrne--both of which saw the artist working in a much more straight-forward pop setting than previously--Feelings combines his light touch with melody with faint colorings of other styles--Cajun, Brazilian, salsa and swing--and the result is musically very pleasant. Guests include Brazilian singer Vinicius Cantuaria, pop star Paula Cole, soul singer Betty Wright and members of Devo; and the majority of the record is produced by English trip-hop group Morcheeba. Lyrically, however, is one place where you either stay or go with Byrne. "I kissed America / when she was fleecing me," he sings on "America," a song that is a horrid cross between "America" from West Side Story and the sentiments of Nine Inch Nails' "Head Like a Hole." In other words, very ironic. "Finite + Alright" is the album's catchiest number: "Another Elvis will not come along / It's scary but alright / Everything is finite." When Byrne is less deliberately ironic, however, he is far more tolerable. Highlights of the record include "Daddy Go Down," a Cajun country lament played by English people on sitar and violin; "Dance on Vaseline" (which is reminiscent of such Talking Heads hits as "Wild Life" and "Burning Down the House"); and "The Civil Wars." "They Are in Love" is a junkie song, recorded in Seattle, which concludes, "It's the pain that keeps us alive / but beauty is all we need to survive." That's a pretty trite conclusion coming from someone as detached as Byrne usually is. And yet, there's something reassuring about its very banality. Maybe he's not an alien after all.

David Byrne plays the Warfield, 982 Market St., San Francisco, at 8pm on Aug. 2829. Tickets are $22.50/$20. (BASS) [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.