![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

The Torch Is Passed: Longtime CET staffer and new director Hermelinda Sapien took over the reins of the nation's premiere welfare-to-work program on August 6 from co-founder and former director Russ Tershy. CET observers say if anyone can revitalize the troubled organization, Sapien can.

The Torch Is Passed: Longtime CET staffer and new director Hermelinda Sapien took over the reins of the nation's premiere welfare-to-work program on August 6 from co-founder and former director Russ Tershy. CET observers say if anyone can revitalize the troubled organization, Sapien can.

Photograph by Christopher Gardner

Too Big Too Fast Washington wanted a model welfare-to-work program to take on the road. San Jose's Center for Employment Training was happy to oblige. It was a recipe for disaster. By John Yewell FOR A MAN whose life has been turned inside out over the last three and a half years, Jose Gomez maintains a pretty cheerful disposition. Maybe it's because for our first interview he's surrounded by his four children in the living room of the family's tidy Watsonville home. Or maybe it's because, lately, things are looking up. Jose's 22-year-old son, Joel, a security company supervisor, helps interpret, while Jose's wife, Maria, busies herself in the kitchen, walking occasionally through the room and smiling shyly. Daughters Adriana, 13, and Stephanie, 12, sit quietly on the couch near their father, listening politely. About 6pm, with the conversation nearly two hours old, 24-year-old son Heriberto, a student at the San Francisco Culinary Institute who is visiting for the weekend, excuses himself. It's Saturday night and he has to go to church. The translation process is slow, so Jose occasionally tries gamely to turn the right English phrase--he very much wants to tell his story. It begins in March of 1996 when, at the age of 54, after 23 years with the same company, he suddenly found himself out of work. Norcal Crosetti Foods laid off 700 workers, joining a long list of food processing firms going under or leaving Watsonville. Over the next year, Gomez would struggle through difficult economic times, the death of his mother and a disabling heart attack. The one bright spot, he thought, would be getting into a training program that promised a job as well as financial support during the training. The program was at a school called the Center for Employment Training, commonly known as CET. Things would not turn out the way Gomez hoped.

Working Assets: More information on CET.

Soto Voce FOR 29 YEARS, Russell Tershy and Anthony Soto had been an unstoppable team. Soto had come to San Jose in the 1960s to be the pastor of Our Lady of Guadalupe church in East San Jose. He became active in the Catholic social reform known as Cursillo; among his students were farmworkers union leader Cesar Chavez and Bob Gonzales, father of San Jose Mayor Ron Gonzales. In 1967, Tershy, after working as a young Christian social worker in Chicago and then for the Peace Corps in Bolivia, hooked up with Soto to start the Center for Employment Training in a schoolroom at Our Lady of Guadalupe--a kind of social services parallel to the garage birth of Apple Computer. The first class was a machine-shop course. In a country hungry for success stories about moving people off welfare and into good jobs, CET became legendary.

Photograph by Christopher Gardner

With Soto as chairman of the board and Tershy as CEO, CET grew steadily, especially in California. The organization's philosophy was simple: train people--regardless of their backgrounds--for real jobs and take care of remedial problems such as language along the way. Most important, build ties to industry. At CET, there is no such thing as graduation--only getting a job when you're ready. At its San Jose headquarters, the majority of the clients are Latino, and many are unemployed farm workers. The center's motto: Si Se Puede--It can be done. Eventually, the kudos began to roll in. In 1990 a Rockefeller Foundation Report hailed the program as being in a class by itself, which resulted in articles in the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and Los Angeles Times. In 1992, the Department of Labor gave the center a million-dollar grant to "replicate" its success around the country. In 1993, a study by Manpower Demonstration Research showed that CET's graduates were moving into much better-paying jobs than graduates of a dozen other training programs around the country. After the 1992 election, Tershy was briefly considered for a cabinet post in the Clinton administration. In February 1994, Secretary of Labor Robert Reich visited CET's San Jose headquarters and praised the center. With the economy struggling toward recovery, there were plenty of people who needed help and CET was busy. In 1993, using the Department of Labor funds, CET embarked on an ambitious "replication" program, opening new centers around the country--and setting in motion forces that would eventually undermine the center's success and threaten its existence. Early in 1996, the wheels began to come off. In late January, Russ Tershy said goodbye to his longtime friend. At age 74, Soto died of cancer. Just weeks later, about the time Jose Gomez was hitting the bricks in Watsonville, Department of Education auditors were knocking on CET's door with questions about unaccounted-for federal dollars. And the replication program was bleeding cash. Gomez and Tershy were about to become players in the organization's dramatic downward spiral. By April 1998, the Department of Education investigation would result in a demand that CET repay the feds $2.85 million dollars. Gomez, meanwhile, would be looking for his small portion of the same pot of gold--a $2,470 grant from the Department of Education that CET officials had promised him but never paid. Finally, last July 19, after 32 years at the helm, Tershy resigned--his two-page letter of resignation was accepted by his board of directors on Aug. 6. The board named deputy director Hermelinda Sapien, who had also been with the organization since the beginning, to replace him. It was the end of an era. Pell Mell JOSE GOMEZ supervised the loading of the trucks and trains carrying the company's produce. If the manifest said a container held 100 crates of cauliflower, he says, you could be sure it did.

Gomez came to the U.S. in 1972 at the age of 30 from his home village of San Sebastián, in the Mexican state of Jalisco. His first year he worked in a restaurant in Long Beach and got his residency papers. In 1973, at the urging of his brother, he came to Watsonville. Gomez arrived on a Friday night and was hired the following Monday morning, staying with the same company to the end. He started at $3.15 an hour. Later he arranged for Maria to come from Mexico to join him, and they started a family. In the early days he sometimes had to work more than one job to make ends meet, but by 1996 he was taking home $450 to $500 a week after taxes. Life was good. When he was laid off, Gomez says at first he received only $141 a week in unemployment. After 23 years in the same job, and without a high school education, Gomez turned to a Santa Cruz County program called CareerWorks, which put him in touch with CET. He decided to go into commercial food preparation, but there was no training program at the CET facility in Watsonville. So in July 1996, Gomez and a dozen other unemployed workers went with CareerWorks caseworker Salvador Luquin to San Jose to check out CET headquarters, which had a large kitchen facility and training program. Gomez liked what he saw, and found the center's employees to be helpful. So on Aug. 27, Gomez was back in San Jose to sign up. An enrollment agreement spelled out his financial aid package, including $6,300 for tuition from Joint Training Partnership Act (JTPA) funds through the Department of Labor. There was also a Pell grant (direct post-secondary student aide administered by the Department of Education) of $2,470. The center also arranged for Gomez and other displaced Watsonville workers to commute daily to San Jose in a CET van. Gomez signed everything that was put in front of him. It was all in English. CET Knows Best ON MARCH 11, 1996, a few weeks after Soto's funeral, auditors from the Department of Education's San Francisco field office arrived at CET's San Jose headquarters for a scheduled audit. Sources close to the investigation agreed to speak with Metro Santa Cruz on condition that their names be withheld. During their five-day stay, the auditors found the company's records in a shambles. The available data revealed a pattern of unaccounted-for funds, double billings, unpaid Pell grants and voided checks. On Sept. 13, shortly after Gomez had begun his training, the Department of Education issued a damning "program review" report. "The continuing occurrence of severe programmatic and fiscal deficiencies ... is evidence of the Institution's reluctance to implement and monitor effective procedures to ensure regulatory compliance," the report read. "Such a deficiency casts considerable doubt about the administrative capability and financial responsibility of the institution." The review made 21 separate findings against CET, including improper student account balances, inadequate financial aid counseling and improper accounting for Title IV federal student financial aid funds.

Among the charges was the claim that CET kept Pell money owed to students, based in some cases on students' signature on a form called Statement Regarding Credit Balances. The form allowed CET to withhold a student's grant and disburse it on behalf of the student to cover educational "costs"--at the center's discretion. For all its legendary commitment to the poor, CET's response to the program review, issued two months later on Nov. 15, revealed how, after 29 years, a certain father-knows-best attitude had crept into the organization. There was scant acknowledgment of internal problems. Rather, CET justified retaining control of Pell grant funds by saying that "sociological, economic, and cultural factors inherent to the disadvantaged population we serve are pulling the student in contrary directions." The center seemed to feel it could manage students' money better than the students themselves. Signing the Statement Regarding Credit Balances was supposedly voluntary, but Department of Education auditors found no examples where it wasn't signed, and none of the students interviewed who had signed the form realized they had given up control of their money. Meanwhile, the Department of Education was unable to account for how the money was actually being spent. In his response letter, Tershy threatened to go over the inspectors' heads to a D.C. friend, Undersecretary of Education David Longanecker. In an interview, Tershy admitted speaking with Longanecker but claims nothing came of it and that no pressure was brought to bear on department auditors. Still, when the final program report was issued in April 1998, there was no request for a punitive assessment--something the department had a right to request. By far the biggest impact of the review was the placing of CET on "reimbursement" status--revoking the organization's ability to automatically draw Education Department funds directly from a government account. From then on, CET would be required to apply for each dollar based on proof of student enrollment. This stricture resulted in a financial bottleneck that was exacerbated by increasing losses in the replication program. It contributed to a cash crunch and crisis fiscal management that was felt throughout the organization, most acutely by people like Jose Gomez, the people CET was created to help--and who could least afford it. The Replicator ON SEPT. 30, 1996, barely a month after signing on with CET--and just weeks after the organization was placed on reimbursement status with the Department of Education--Gomez traveled to Mexico for his mother's funeral. After he returned on Oct. 8, he began to wonder when he would get the rest of his financial aid money. As fall moved into winter, CET's financial fortunes worsened. According to company financial reports, the center's Pell receipts in 1995-96 totaled $5.2 million dollars, but thanks to the fiscal diet it was now on, those receipts would plummet to $1.5 million by the end of the 1996-97 fiscal year. For a $35-million-dollar-a-year company, it was a big bite. Meanwhile, new CET centers in Los Angeles, San Francisco, New York, Baltimore, Arlington, Newport News and elsewhere were hemorrhaging. According to financial records confirmed by director Sapien, the new centers would accumulate operating deficits of more than $3 million during the period July 1, 1993, to March 31, 1998. In a memo to Tershy dated June 18, 1998, company financial advisor Rudy Vargas detailed some of the mistakes the center had made with its replication program. "We underestimated the intricate and enormous bureaucratic hoops and long delays resulting in state and local approvals before starting training operations," Vargas wrote. "As a result, CET had staff on board, trained and ready to enroll students but had to wait until state and local approvals were completed. Without students bringing in tuition revenues while paying staff and other expenses, start-up costs were higher than projected."

Other CET documents describe difficulties such as insufficient local political support, weak links to local industry and employers and a lack of grassroots organizing. None of this should have come as a surprise. The Labor Department replication contract requires that all start-up, site development, staffing and operation costs be borne by CET. "They opened more facilities than they could handle without evaluating the impact and revenue sources," said one former CET official who requested anonymity. "It was a seat-of-the-pants operation." There was a feeling that anything CET touched would turn to gold, added the official. "When we did things right, we did them very right. The attitude at the top was 'We can walk on water.'" Eventually, by the end of 1999, of 24 replication sites in 13 states and the District of Columbia, nine would be closed and nine more would be turned over to local community-based organizations. Only six remain operated by CET. Meanwhile, Jose Gomez simply wanted to know where his Pell grant was. Then on Jan. 21, 1997, Gomez was felled by a heart attack. He was not able to return to his training until March 17, but in the meantime one of his teachers, Ricardo Cortes, gave him homework to keep up with the classroom portion of his training. His doctor, Mark Byrne of Watsonville, forbade heavy lifting. By the time Gomez had effectively finished the food course in September 1997, he was on disability and virtually unemployable. At the end of his training, Gomez was told by a CET official that he would receive a letter explaining how much Pell money he was eligible for--although he thought that had been settled when he first signed up. He waited. No letter ever came. Soon it was 1998, and still he had not received a dime of Pell money. Clearing the Decks AS 1997 DAWNED, the twin impacts of the replication losses and the Education Department tourniquet grew worse, sparking an internal battle over how to rescue the organization. Eventually, Tershy would side with those who recommended that the group sell its seed corn, a carefully amassed portfolio of properties including prime downtown San Jose real estate, that had been bought cheap and managed by CET Development, a spinoff nonprofit holding company. Peter Carter, a San Jose ad exec and former CET Development board chair, was among those who argued against liquidating assets to pay bills--especially in the absence of the kind of changes that would staunch the flow of red ink.

"The objective of the board [of CET Development]) was to help CET put together a long-term annuity in the form of real estate," Carter explains. "When operational problems were not being corrected and were draining the organization horribly, we had an understandable reluctance to liquidate the portfolio wholesale with no indication it would do anything other than provide a temporary fix. When we made that clear, we were summarily fired." No one suggests that Tershy ever enriched himself personally, but some observers believe that the heady attention from the Rockefeller Foundation and the Clinton administration made Tershy unwilling to throttle back on the organization's ambitious expansion plans. By the summer of 1997, something had to give. Tershy eliminated the accounting department headed by Frank Zamora, a divestiture opponent, and brought in Vargas, who had previously audited the company's books, as a consultant. Tershy and the CET board then dismissed Carter, along with the board of CET Development and its executive director, Jose Jimenez. According to press accounts, petitions started circulating at headquarters demanding Tershy's removal. But with Zamora, Jimenez and Carter out of the way, Tershy was free to sell off the properties to pay his bills--which he began to do. Balance Due BEHIND THE SCENES, the Department of Education investigation continued. Due to what it called the "unresponsive nature" of CET's reply to the 1996 program review, the department followed up with two more visits to CET headquarters, on Jan. 13 and April 7, 1997. A year later, on April 29, 1998, the hammer fell. The "Final Program Review" detailed the most serious allegations yet of mismanagement by CET and recommended administrative action in the form of a $2.85 million "liability assessment." From a sample pool of 691 students, Department of Education auditors found that 195 did not get money they were supposed to receive or that their accounts were in some way improperly maintained. They arrived at the liability figure by extrapolating from the sample. Along the way they found that:

"Withholding student credit balances," the report went on, "results in the institution receiving funding to which it is not entitled and causes needy students to be deprived of Title IV [educational aid] funds." CET claims that about half the disputed funds are merely the result of a tiff between the Departments of Labor and Education over a financial aid program for farm workers. The Department of Education says CET got rebates from the Department of Labor for Pell money paid to the department to help cover tuition, but CET never passed the extra money along to students or used it to retrain additional students. If the auditors are right, it would suggest that the center, caught in hard times, was using money intended for needy students to bolster its sagging bottom line. An official close to the investigation says it is likely some students dropped out of the training program altogether as a result of these actions. In its response to the allegations, CET's lawyers zeroed in on the Department of Labor's federal farm-workers assistance program, claiming that if CET owes money to anyone, it is the Department of Labor, not Education. The response largely ignores the other allegations in the Final Program Report, such as the voiding of checks, retention of Pell grants and overcharging of tuition. Final briefs were delivered to an administrative law judge in Washington, D.C., Aug. 20, 1999. A decision could be weeks or months away.

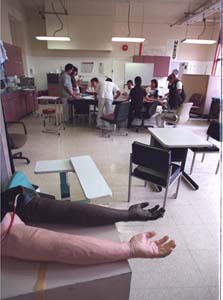

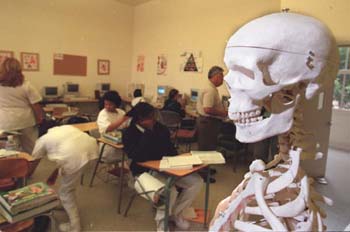

Case Files AS THE SUMMER of 1998 approached, Jose Gomez was as determined as ever to find out why he still had not received his Pell grant. He spoke with his teacher, Rocio Buitron (who no longer works for CET), she told him he didn't qualify for the Pell but offered no explanation. He spoke with his teacher, Ricardo Cortes, and asked him to check on it for him. "There was something of a discrepancy in the paperwork on CET's part," Cortes says. "He was an excellent student, kept in touch, did a lot of homework, got his certificate." Soon, Gomez happened upon the offices of Senior Legal Services in Watsonville. Inside, legal assistant Sara Paz listened to his story and agreed to help. There followed a series of letters to Tershy (dated July 8, Aug. 24 and Sept. 25, 1998) requesting information on Gomez's grant. CET did not respond. Finally, early in 1999, Paz approached Assemblymember Fred Keeley. Reed Addis, a Keeley aid, sent letters on Gomez's behalf to CET, and Gomez finally received a check on April 7, 1999--for $1,457.30. It came with a statement in English and Spanish, which CET asked him to sign, promising to accept the amount as full payment. On Paz's advice, Gomez cashed the check but did not sign the statement. After another flurry of letters, he finally received the remainder of the $2,470 in the mail about two months ago. Mercury Rising GONE ARE CET's major parcels at 425 S. Market St. and 500 S. First St. in San Jose, and some housing units on Locust Street, with more property on the block. According to financial advisor Vargas, as much as $2.5 million of the $3 million netted from those sales went to pay operational expenses--precisely the scenario Carter and others at CET Development had sought to avoid. As a part of the effort to get control of the cash drain, four more parcels were recently sold or placed in escrow. Two more unprofitable training centers are scheduled to close by the end of this year. The biggest part of the refinancing is an $11-million private bond issue, financed by Finova Capital Corp. of Phoenix, Ariz. The deal is essentially a swap of high-interest mortgages for lower-interest bonds. Some cash was realized from this deal, but its main purpose was to lower operating expenses, including equipment leasing costs. Finova basically became CET's banker, with refinanced property and equipment as collateral. Despite a potential liability of nearly $3 million to the feds, Finova seemed unconcerned. Stephen Crawford, vice president and regional manager for Finova, who negotiated the deal, said in an interview: "They won't likely have to pay it." No? How so? "It's more of a dispute over how money was spent," Crawford says, "not to whom it is owed." Crawford adds that correspondence between Finova, CET and Department of Education officials convinced Finova that the possibility of a major assessment of liability against CET was remote. At CET headquarters, Tershy confirms that CET's lawyers are trying to cut a deal with the Department of Education, and figure their risk at perhaps $300,000. That's not the view of those close to the investigation. "Any negotiated settlement over $100,000 would have to be approved by the Justice Department," says an official close to the Department of Education investigation. "We wouldn't be going to all this trouble if we were going to settle cheap." Resigned to Fate THE OLD WOODROW WILSON Junior High School in San Jose that houses CET headquarters has that faded charm common to old public buildings, where no amount of spit and polish can disguise ancient concrete and worn linoleum. On the main floor wall near the entrance is a huge photo of Russ Tershy with Hermelinda Sapien, Cesar Chavez and Anthony Soto. On a pedestal below sits a bronze bust of Soto. Max Martinez, CET staff training director and a key player in the replication program, gives us the VIP tour, showing off the kitchen, the child care areas and the various trade skill classrooms. He seems particularly proud of the machine shop's new computer numerically controlled milling machine.

In the electrical classroom, we meet Azucena Lopez, a 21-year-old single mom from King City recently idled by the strike there against Basic Vegetable Products. It's only her second day, and it's a long commute by CET van, but Azucena seems happy to be here--and determined to acquire a useful skill. Having a child at 17 has taught her one thing, she says: she doesn't want to have to depend on a man. When we get upstairs, new director Sapien ushers us into her office, where we sit at a round conference table. She seems momentarily taken aback when asked about the circumstances surrounding Mr. Tershy's recent resignation--there had been no formal announcement--but after 32 years with CET, she reacts like someone who has had to deal with her fair share of crises. A few minutes later, Russ Tershy enters the room. He is a small, animated man with a striking head of bushy silver hair. He loves to answer questions--no matter to whom they're directed. At age 78, his eyes still twinkle, but it's a worried twinkle. His resignation as CEO of the organization he made his life's work had been accepted by CET's board of directors just five days before, and he acts like a man still coming to terms with the fact that he has to move on. He is a man obsessed with his legacy, one that includes helping tens of thousands of people out of poverty, so the more nettlesome questions trouble him--they get in the way of the positive story he wants to make sure gets told. He even denies, at least initially, that the CET programs in other cities had lost money--despite ample documentation to the contrary. As for his resignation, Tershy says, there was nothing precipitous about it. In fact, he says, he'd been contemplating retirement for several years. But by some accounts, the events of the last two months accelerated matters. According to sources inside and outside CET, the beginning of the end of the Tershy era got a kick-start on June 27, with a San Jose Mercury News article that many felt painted an overly optimistic picture of the center's financial health. There are rumors of a staff revolt similar to the 1997 skirmish, but Sapien denies it. However, in a phone interview the next day, Sapien admits that the Mercury article "may have had a catalytic effect." "Some people externally and internally may have interpreted that as an overly positive outlook and felt that it wasn't the full story," she says. Because of CET's financial troubles, some staff members thought that things were not going as well as they were portrayed in the article. "But we feel that we are now on the right track," she says. "The financial situation is crystallizing itself. We're doing much better." Brave New World EVEN TERSHY'S DETRACTORS describe him as well motivated, if occasionally misguided. They want to believe that CET is now on the road to recovery--and if anyone can make that happen, they say, it is Hermelinda Sapien.

Photograph by Christopher Gardner

One former official suggested that the funding problems of United Way of Santa Clara County earlier this year may have helped shock the CET board into getting its house in order. "Hermelinda is a caring, committed person," says the official. "She has sacrificed a lot to be there. She loves the work and the entity. "The reserves are gone, but people are more hopeful. In late June things were very gloomy." Tershy says he plans to stay on as a consultant, perhaps until Dec. 1. In his resignation letter, he thanks a long list of supporters. Tops on the list: "The late Anthony Soto, founding Board Chairperson, who remained with CET until his life ended." With his deep belief in the center's mission, Tershy refers to the organization he founded variously as a "movement," "a mission," a "community," a "family" and a "model." To work there is to toil in the CET "vineyard." Workers are "missionaries." Was his passion betrayed by incompetence, a missionary zeal that never got a handle on the vagaries of government paperwork? Or did the needs of the institution's bottom line undermine the work, overshadowing the needs of the people whose mission it was to help? How will all that be stacked against the obvious accomplishments of the organization? And what of Jose Gomez? In the end, he was one of the lucky ones--others interviewed for this article never did receive funds they said were promised to them. He's getting by OK on a combination of his union pension, Social Security and Medicare. Dr. Byrne says his treadmill tests look good, and he may be able to go back to work soon. And after everything, the reason he didn't get his Pell grant until nearly three years after he started at CET was simple: CET forgot to submit his application. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the August 26-September 1, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

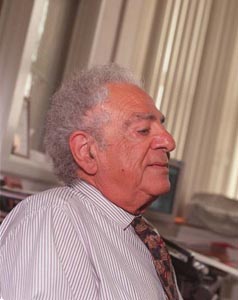

The Vision Thing: Despite CET's management problems, most laud outgoing CEO Russell Tershy for his commitment to helping the poor and unemployed.

The Vision Thing: Despite CET's management problems, most laud outgoing CEO Russell Tershy for his commitment to helping the poor and unemployed.

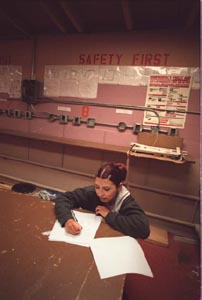

Hope Invested: Hermelinda Sapien was present at the birth of CET 32 years ago. As the new CEO, it's now her job to see that it doesn't die.

Hope Invested: Hermelinda Sapien was present at the birth of CET 32 years ago. As the new CEO, it's now her job to see that it doesn't die.