![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Down on the Valley

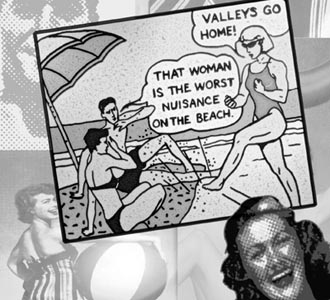

Mott Jordan A born-again Santa Cruzan who's logged time on both sides of the hill declares a truce in the war against the Vals By Eric Johnson SANTA CRUZANS are as mellow and gentle a population as exists anywhere. But a lot of those folks, even nice people, will stiffen, smirk or sputter when asked to talk about their visiting neighbors from the Santa Clara Valley. Santa Cruz has long had a love-hate relationship with the people from Over the Hill. We love their tourist dollars but hate the traffic. We love that they like our town, but we hate the mobs at the beaches, hate the crowds in the surf zone, hate the lines at the breakfast restaurants. Nobody will say it out loud on the record, but put down the pen and they'll talk. Or offer them anonymity--the gripes will begin to flow. "I like real tourists, people who come stay in hotels and eat in restaurants," says a guy I'll call Bob. "But these day-trippers from the valley, they just come over here and crowd up the beaches and streets and make a lot of noise and big mess." This perfectly affable professional, who lives in the Seabright neighborhood, goes on for a while, working himself into a near-frenzy, then cracks up. "I'm sorry," he says, laughing self-consciously at his own rudeness, "but I wish they'd just stay away!" This attitude comes with the territory. It's a beach-town thing. Coastal people around these parts have quarreled with their neighbors for more than 5,000 years. The people whom anthropologists lump together as Coastanoans or Ohlones--as though they were one tribe or nation--had almost nothing to do with each other. The band that lived up on Whitehouse Creek, just north of Año Nuevo, for instance, didn't even speak the same language as the tribe that lived on Aptos Creek 30 miles south. Nor did they fraternize with the people who lived up on Gazos Creek a few miles north. Occasionally, folks from these bands would interact--when someone wandered into another territory in search of blackberries. These invaders were generally given a taste of some homeboy's chert-tipped spear. Even then nobody liked day-trippers. Back on the Jersey Shore, we called them Bennies. They came for the "beneficial rays," according to legend, and, in order to get on the private beaches, they had to wear silly little paper "Bennie badges" on their swimsuits. The cool, stamped-metal resident-badges that my buddies and I wore on our Levi's cutoffs were shields that marked us as locals. We put up with the pale throngs who arrived blinking and stumbling on the boardwalk every day. But we looked down our noses at them. Before they'd even had a chance to get their sand-legs, the Bennies had to go back upstate, or to the city, or to Pennsylvania or wherever. We were the Chosen, the beach kids. We lived there (which for most of us meant we had friends with nice parents who let us roll our sleeping bags out on their screened-in porches). It was our beach. So I know how the folks in the anti-valley contingent feel, even if I don't agree with them. 'My' Tourist Mecca THIS TERRITORIAL ASPECT of American beach-town culture lives on today, from Point Pleasant, N.J., to Pleasure Point, Calif. It can be seen in the spray-paint graffiti on an asphalt trail just south of Año Nuevo, which says LOCALS ONLY BEACH. (Twenty feet up the road, as an odd afterthought, it says NO PICTURES.) On the tiled wall in the men's room of a Soquel Avenue bar, the same feeling is expressed simply--under a funky graffiti tag signed by a guy from San Jose, someone has written GO HOME. For a decade or more, a similarly inhospitable message was scrawled on the overpass where Highway 17 intersects Highway 1: VALLEY BUG OFF. If it was there for 10 years, as many as 230 million cars passed under that sign, a big chunk of them from San Jose and its suburbs. Valley Go Home--it's the battle cry of coastal provinciality. Turf-conscious high schoolers shout it from cars. Annoyed surfers carve it into cliff walls. Tense businessmen stuck in the summer-long traffic jam surrounding the corner of Seventh Avenue and Murray Street mutter it under their collective breath. Bob has given some thought to the subject, and he has worked it into something like a political position or a conspiracy theory. "The city is doing everything it can to make Santa Cruz more like San Jose," he insists. "They [the City Council, et al.] want the people from the valley to feel comfortable, so they build places like Gateway Plaza. Then the Vals can say, 'Oh, how nice, it's like home, but with a beach.' Meanwhile, our cool little funky, artistic town gets turned into a mini-Silicon Valley." Outside the percentage of our population who are hard-core unapologetic grumps, this animosity is nowhere near universal--nor does it run very deep. Santa Cruzans do not, like snooty Parisians, have a reputation for hating everyone in Europe and the rest of the world outside their city. The citizens of Surf City are famously friendly, even to their cousins from over the hill. They will admit that the throngs that descend on our beach town every weekend all summer are a necessary evil, but if a lot of the locals had their druthers, the Vals would keep out. For a long time, it has been an accepted commonplace that Bob's theory is correct--and not merely among the curmudgeonly anti-business types. Back in 1985, Joe Flood, who was at the time the head of the Convention and Visitors Bureau, told the Santa Cruz Express that folks who came here on an excursion from the valley did little to help the local economy. He went on to bemoan the fact that we here in Paradise-by-the-Sea are stuck with day-trippers. "There's absolutely nothing you can do about them, unless you get rid of the Pacific Ocean," he said. "It's a problem that will never, ever go away. They're going to come no matter if we build barricades over Highway 17. They will climb them." Love Thy Neighbor TWO YEARS LATER, tourists from San Jose were again slammed in print, this time by higher-ranking local civic leaders, in a Metro article by a pseudonymous scribe calling himself "Bubba Golden" (a.k.a. Sam Mitchell). Former Santa Cruz Mayor Jane Weed told the reporter that anti-valley sentiment was "not overblown at all. They buy everything they need over there [in San Jose]," Weed said, "and consume it over here," leaving a mess, and contributing not a nickel to support local services. ThenSanta Cruz County Supervisor Gary Patton agreed, saying the low opinion of visitors from the valley was "a reasonable reaction" to a bad situation. Santa Cruz Police Chief Jack Basset chimed in that "day-trippers create the majority of our service demands in the summer," and railed against those who "come over here with their own cooler and six-pack and get drunk on the beach, raise hell and go home." But official opinion of regional tourism has changed considerably in the ensuing 10 years. Joe Haebe, an SCPD watch commander, now says that while it's true that the city's crime rate goes up in the summer--especially around popular tourist beaches and the Boardwalk--there is no evidence that the increase is attributable to out-of-towners in general or Vals in particular. The Seaside Company takes care of its own trash at the Boardwalk and is certainly not going to complain about that. Nor will anyone from the city or county parks departments point fingers at tourists for the trash that these agencies are charged to clean up (although, following the defeat of a bond measure in April, the county has decided to curtail garbage pickup, whether the litter was created by home-towners or guests). Similarly, the local state parks chief refuses to place blame on valley residents for the mess his staff rakes off its coastline every morning. Santa Cruz Mayor Cynthia Matthews, when asked to comment on visitors from neighboring municipalities, sings a far sweeter tune than her predecessor. "A number of things have happened in the past 10 years," Matthews says. "There has been a fundamental shift in our understanding of the impacts of tourism." The change of heart is partly due to a series of studies that have shown that day-tripping Vals do in fact contribute to the local economy. That was helped along a few years back when a 5 percent "admissions tax" was tacked onto the price of every theater and event ticket in town. "There is no doubt about it," Matthews says. "They eat in the restaurants and shop in the galleries. You can't have the jobs, the work for actors, the audience for artists and all of these things we love without these people. I'm sorry, but we are not a major metropolitan area." Her Honor sounds sincere, and she has no reason to dissemble--these people can't vote for her. But they do take advantage of services that are financed by taxpaying Santa Cruz County voters. Nobody has tracked the real dollar costs of the tourism industry. City and county expenditures on recreation and cultural services total $7 million, and for other services tourists use--such as roads and parks (including beaches)--local taxpayers pitch in another $25 million. Nobody has calculated what percentage of that cash outlay is made necessary by tourists. But everyone from the director of the CVC (or Conference and Visitors Council, the renamed local tourism agency) to the Tuesday-night bartender in any local pub recognizes the value of tourism--and loves the money these visitors bring in. Tourism is the No. 2 industry in Santa Cruz County, behind agriculture--No. 1 if you break down the ag numbers into distinct categories. Tourists spend more than $400 million a year here. They contribute $8 million to the local tax base--more than $5 million of that comes from the temporary occupancy tax (or bed tax). The 5 percent admissions tax adds another $1.5 million. Visitors to Santa Cruz add another $15 million to the state's tax coffers from the bed tax--much of which is returned to the area. According to the CVC, eight million people visit this county each year. CVC estimates that 60 percent are day-trippers who come in groups of three or four and spend $125 per group. The rest are small groups of overnighters (Bob's "real tourists"), who spend more than $600 on average. A survey by the CVC finds that 74 percent of our visitors come from parts of Northern California. Wildly assuming that half of those are our nearest neighbors, roughly figuring for the fact that these are (probably, mostly) day-trippers--let's see, subtract a few million to be safe--that puts the valley's contribution at more than $100 million in business and maybe $10 million in taxes.

Not-So-Hidden Costs IF IT'S IMPOSSIBLE to quantify the dollar benefits of "local" tourism, it's even harder to detail the exact costs. Nevertheless, it appears that if all the economic benefits of tourism were placed on one side of a scale and the costs on the other, the thing would tip over. But there are the other costs associated with our hospitality business. Tourism is widely touted as a clean industry. True, tourists don't do as much harm as smokestacks, clear-cuts or careless microchip factories. But while the environmental costs of tourism are even harder to pin down than the economic costs, they are undeniable. Traffic is clearly the biggest problem. Driving anywhere near the beach, or on Highway 1 for that matter, can be aggravatingly slow between June and August. Traffic reports confirm that on tourist routes like Ocean Street, Mission Street and Riverside Avenue, there are more than twice as many motorists in July as in March. Between 10 and 11 on any summer Saturday morning, almost 6,000 cars pour over Highway 17--a fact that is disconcerting to anyone stuck at a cross street. And all these cars, of course, bring added air pollution, something less obviously annoying but perhaps as dangerous. Beyond that, tracking the hidden costs of tourism gets squirrely. But everybody who lives here has anecdotal evidence that our quality of life is negatively impacted by the throngs. Like everyone else, I can tell tales of tourist-inflicted woes. Soon after returning to Santa Cruz this April after a 15-year hiatus in uncrowded Montana, I settled into a couple of nice little after-work routines. I'd bike from the place I was renting on 30th Avenue, out along East Cliff, and cruise through Capitola, then head out Park Avenue to New Brighton Beach, where I'd jog out to the cement boat. On other days, I'd drive to La Selva (where I'd lived 20 years ago) and wander the empty beach at Manresa. I don't have to describe how these experiences were altered when the tourist season arrived. But I will. East Cliff is a mob scene. Bike through Capitola? Forget about it. The crowds at New Brighton are fun to look at, but they completely distract me from the sunset, surf and pelicans, which is what I go there to see. Manresa is still gorgeous, but I feel a little dumb joining the long line of joggers dodging dogs, cute little kids and sand castles. In July, I moved to a dead-end road outside Soquel. This time of year, I stay home a lot. I hike around the neighborhood. Hidden Benefits IN OREGON, THE LOCALS don't differentiate between the Golden State's Vals and coastal dwellers. The bumper sticker says "Don't Californicate Oregon." In Montana, they don't care where you're from--mudflaps on pickup trucks from the cow-town of Billings to the university town of Missoula read "Gut Shoot 'em at the Border." They don't mean Canada. It's genetically impossible for me to subscribe to this provincial attitude. My grandfather grew up an Irishman in Liverpool. He left England to live in Barbados before moving to Harlem, where my mother was born. My other grandfather brought his family to New York from Sweden. My parents moved to New Jersey from the Bronx. My people have always been from somewhere else, like many Americans, including a lot of Santa Cruzans. Besides, I'll admit it: I love San Jose. I still remember the first time I saw it in 1968, flying in from Newark. As we came in over the South Bay, I gazed down at what looked like a big suburb, at the golden hills that poured down from the east, and at the redwood-covered mountains and the sea beyond, and I thought "California!" I was in love already. We stayed with my Uncle Jack, who lived on the west side of the valley, a mile from where my mother now lives. It was newer, cleaner and sunnier than New Jersey, and to my 13-year-old eyes, that was all good. On the second or third day of our visit, my cousin John mercifully dragged me away from the grownups for a drive. We climbed into his buddy's '61 Impala and drove out Saratoga Avenue, then continued up Highway 9 to Skyline Drive, where we parked near Castle Rock. I looked out over the San Lorenzo Valley, and out over the Monterey Bay, and knew I'd found my home. I moved to California five years later, fresh out of high school. I rented a room in cousin John's house in Campbell--which in those days was a short drive through a hundred orchards from downtown. But even though I enjoyed life in the valley, the thing I liked best about it was its proximity to the redwoods and the beaches. And so, for 11 months, I was one of Them--going over the hill every chance I got. I didn't last long. Less than a year after ditching New Jersey, I moved to Lompico, enrolled in Cabrillo and became one of the Chosen again. But even back then, I didn't quite get the Valley Go Home thing. I had friends and family over there, and I became defensive when people mocked Vals. With the righteously reasoned conceit characteristic of haughty 18-year-olds, I viewed the anti-valley contingent as, well, immature. What is this, I'd sniff, some kind of high school rivalry? Then something happened that deepened my good feelings about San Jose: My girlfriend got pregnant. I needed a job. Not a Santa Cruz job--a real job, in the real world. (Metro cartoonist Steven DeCinzo has noted the phenomenon: In one cartoon, under the sign for the Mystery Spot, a guy wearing a "tour-guide" T-shirt straddles a line separating "Santa Cruz" from "San Jose." He's talking to a tour group, and he says to them: "See! My wages get big on this side, and then get real small in Santa Cruz! We can't explain it!") Real-world wages are not readily available in Santa Cruz. That's because Santa Cruz is not in the real world. People come here to get away from the real world, and it works. Everyone who lives here delights in that. We brag, every one of us, about the fact that the San Andreas fault separates us from the rest of America. (C'mon, is that cool, or what?) Of course, when the San Andreas fault did in fact separate this utopia from the rest of the world, everybody panicked. The earthquake's economic and psychic shake-up was the main force that softened official anti-valley sentiment, and it seems to have reverberated out on the streets. Nobody replaced that "Bug Off" bridge graffiti when Caltrans erased it. Even Bob, in unguarded moments, will relent from his anti-valley stance. Last week, after seeing Cirque du Soleil in the shadow of the San Jose Arena with a bunch of my co-workers (almost all Vals), he and I had some great Vietnamese noodles at Lan's Garden on Fourth and San Fernando. He didn't complain at all. Highway 17, going back over the hill, was practically empty southbound. People from Santa Cruz don't go to San Jose much. I don't get it. I suppose being from New Jersey has made me a tad sympathetic to people being put down because of where they live. But my affection for the valley has more to do with the way the place is now. I like the newly minted big-city stuff--from the San Jose Museum of Art to the clubs on South First, but more than that I like the place's utter lack of pretension. OK, maybe people from San Jose do wear socks with their sandals and mousse in their hair at the beach. But they're good people. Come on down, that's what I say. Yes, I wish the restaurants over here were less crowded, but I thank the Vals for making it economically possible for there to be so many wonderful restaurants here. I thank the Vals for the fact that a world-class Shakespeare troupe puts on plays here each summer. I credit the Vals for helping many of our town's artists, musicians and craftspeople prosper, and for spending the money that allows so many great bars and bar bands to flourish. Maybe my personal history affects my ability to see all of this objectively. But I thank the Vals for helping make Santa Cruz the town everybody over here loves so much. Bob still thinks I'm deluded.

Traci Hukill contributed to this article. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.