Lifting up Robyn's Crusty Carapace

Bleddyn Butcher

Robyn Hitchcock reveals a soft, heartfelt side on 'Moss Elixir'

By Gina Arnold

AT THE SXSW music and media conference in Texas last March, English singer/songwriter Robyn Hitchcock kindly took part in a panel discussion titled "Why Rock Criticism Sucks." There, it immediately became his unlovely task to be the sole defender of a much-maligned profession, a job that he fulfilled with both humility and grace.

"Without rock critics," said Hitchcock, "I wouldn't have a career," and he is probably right. Rock critics--on the whole a shy, awkward and introverted breed--are highly attracted to fellow eccentrics, particularly when said eccentrics are (like Hitchcock) both better-looking than they are and more socially apt.

Thus, they have embraced Hitchcock in his every incarnation, first as a member of the obscure and culty Monty Pythonesque band called the Soft Boys, which he began in 1978, later with an outfit called Robyn Hitchcock and the Egyptians, and finally as a solo artist. In that time, Hitchcock has churned out a series of albums that were uniformly witty and charming, if a bit on the nonsensical side, full of songs with titles like "Leppo and the Jooves," "Brenda's Iron Sledge" and "Queen Elvis."

Hitchcock's oeuvre has been hilarious and poignant, a kind of absurdist running commentary on pop. Unfortunately, the world at large seemed to have little use for a debonair Englishmen who writes poignant songs about reptiles, Hoovers (vacuum cleaners, to you), prawns and death, and the innate oddness of his texts hasn't been helped by a tendency to jump labels (in 18 years, he's been on a minimum of 10 labels--surely a record of some kind--and maybe the reason he hasn't found a wider audience).

This year, however, Hitchcock has finally alighted at Warner Bros., a haven for highly regarded eccentrics. His Warner debut, Moss Elixir (there's an alternate version on vinyl called Mossy Liquor as well, which contains outtakes and versions of songs sung in Swedish--very Hitchcock), is 'round about his 19th solo effort.

Musically, it covers much the same territory as the last five or six albums--it's full of chiming, Byrdsian Rickenbackers, droning rhythms and faintly baroque allusions to '60s psychedelica (live, he's been covering Hendrix lately--unplugged). But lyrically, Hitchcock seems to be struggling, finally, to find a more direct voice.

Sure, the record has its inane moments--the occasional Monty Pythonesque line like, "I say Caroline, no need to spell it backwards/that's 'Enilorac!' (from "I Am Not Me") or "De Chirico Street," on which Hitchcock pictures himself being followed home one night by a weighing machine. Most of Moss Elixir, however, is in tune with ordinary human passions like life, death, love, and lust.

THE MOOD here is close to that of 1984's quiet and elegiac I Often Dream of Trains, complete with a clearer emotional current than his previous LPs. "Filthy Bird," for example, is a strange but moving number that has faint political overtones in Hitchcock's chant "a happy bird is a filthy bird," which evokes pathetic images of oil-drowned seagulls on the coast of Alaska.

"Devil's Radio" is an almost explicit condemnation of right-wing talk radio: "Kate said, 'the flowers of intolerance and hatred/are blooming kind of early this year ... someone's been watering them/we were listening to the devil's radio.'"

"Beautiful Queen" is one of Hitchcock's most direct love songs ever. And the opening track "Sinister But She Was Happy," though admittedly full of strange and evocative wild imagery, is positively intelligible: "She was sinister, but she was happy/basically she was the Jean Moreau type/with a cheery smile and a poison blowpipe/like a kind of spider half inclined to free you."

Another great example of this newfound clarity of purpose is on the death-obsessed "Oblivion and You" (the title cut from last year's Rhino rarities LP), which takes the black humor of "My Wife and My Dead Wife" and elevates it, at long last, to something poignant and humane. "Gliding past hedges and clocks," he sings to a dead girlfriend, "off to infinity/I can remember your locks/and your virginity."

Moss Elixir is by no means an easy listen. It takes a few spins to get to the bottom of the album's charms, and Hitchcock indulges in his fair share of tangled verbosity. But as songs like "Oblivion" prove, the real Robyn is at last emerging from his crusty shell, and the soft pink tissue--in the form of heartfelt songs--that lies beneath the carapace is beautiful to see.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

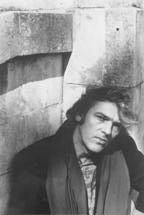

Rock-Critic's Rocker: Robyn Hitchcock's awkward, introverted style appeals to awkward, introverted rock writers.

Rock-Critic's Rocker: Robyn Hitchcock's awkward, introverted style appeals to awkward, introverted rock writers.

From the August 29-September 4, 1996 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/ma-music.gif)