![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

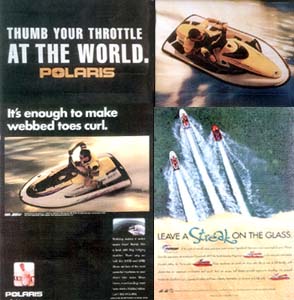

Eat My Mist: Personal watercraft manufacturer advertisements in some cases have capitalized upon open contempt for the environment.

Water Whirled

Must we leave the wilderness in search of peace and quiet?

By Paul Rockwell

THE QUIETUDE OF NATURE is replete with sound. Last month, rod and reel in hand, I hiked many miles to a small lake tucked in the rolling hills of Coe State Park, a vast public wilderness southeast of San Jose.

In late afternoons, hours before twilight, lakes get downright noisy. Frogs begin to converse in the tules. Birds in nearby trees, like families home from a hard day's work, fall into domestic squabbles. Suddenly I heard a cluster of wild turkeys (which sound just like kids imitating turkeys). No doubt they were insulted by my intrusion, waddling into the hills, making a terrible racket.

Then another sound--a joy to fishermen's ears--came from the surface of the lake: tiny splashes and top-water pops as crappie, chasing flies, broke the surface. I was tying a plastic worm and hook (for catch-and-release fishing) to four-pound test line when two deer came into focus. These gentle, stately creatures were standing in bushes not 30 yards away. They didn't move, just watched me cautiously as they chewed the leaves.

The lake on this summer evening was brimming with wildlife, and I was moved.

The Coe Park experience, however, is far superior to many other refulgent California waterways like Lake Sonoma, Lake Berryessa and Lake San Antonio, where I now fish with a certain sadness. The reason is simple: there are no jet skis in Coe, no high-pitched motors, no oil slicks licking wooden stumps, no party-goers doing 60-mile-an-hour stunts, literally in your face.

Coe is one of the few public parks that has managed to resist a growing trend: the motorization of our lakes and the commercialization of our wilderness. Coe is a public lake unmolested by corporate greed and human abuse of technology.

But this is not the case elsewhere in the county.

Let Them Eat Wake: Confessions of an aqua-hedonist.

TO THE WEST OF COE PARK, Santa Clara County is blessed with a necklace of lakes and reservoirs--Uvas, Anderson, Calero, Coyote--a string of nature's jewels just beyond the San Jose metropolis. For many years, the Santa Clara Parks and Recreation Department upheld its mandate "to preserve and protect the natural beauty of our parklands." But things are changing fast.

Coyote Reservoir is a scenic 688-acre canyon lake nestled in the hills south of Lake Anderson, near Gilroy. In the absence of jet skis, Coyote presents an exquisite panorama. From the west shoreline there is a view of rolling hills patterned with sage and scrub oak, where great horned owls and golden eagles sometimes fly. In the small riparian forest there are warblers, flycatchers, ducks and raccoons; and in the south mud flats, waterfowl, even osprey and bald eagles.

Inside the park entrance, the visitor center shows off displays of possum, red fox, skunks, the snowy egret and white heron. One display pays tribute to the Ohlone Indians who inhabited Coyote 200 years ago. A slogan proclaims: "The forest belongs to every living thing."

But leaving the visitor center, heading toward the lake, the first sound of the wilderness most visitors will hear is not the wind in the trees, not the birds and not the frogs. No, it is likely to be the high-pitched sound of zooming, revved-up motors, of jet skis darting in and out and around the lake. The deer are likely to be gone from the shoreline. Waterfowl and long-legged birds that would normally stand at the water's edge will be in hiding.

On weekends at Coyote, even against the backdrop of God's architecture, this once-serene lake looks more like a Coney Island, or some video arcade on water. The jet-ski scene has entirely transformed Coyote's azure water and wildlife.

LIKE SO MANY environmental nightmares, the destruction at Coyote is part of a chain reaction. More than a year ago, the Santa Clara County Water Resources Agency adopted a plan to protect local drinking water from MTBE, the gasoline additive methyl tertiary butyl ether. Long-term health effects are still being studied, but even at low concentrations MTBE can foul the taste and odor of drinking water. MTBE pollution is caused by personal watercraft (jet skis) and other two-stroke motors.

Frank Metzke, who helps oversee the quality of Santa Clara County drinking water, described the early testing process. "We had one reservoir that had nothing but personal watercraft, another that had nothing but boats on it. Where there's personal watercraft, MTBE jumped up to 15 parts per billion. That's high," he says. "We pulled the jet skis off of the reservoir, and the MTBE declined to 2 or 3 parts per billion, an acceptable level."

On June 28, Parks and Recreation imposed a temporary ban on jet skis at Calero Reservoir, due to high levels of MTBE in the water. So the jet skiers rushed over to Coyote, merely transferring the pollution to another Santa Clara drinking-water lake. According to Tamara Clark-Shear, the county Parks and Recreation information officer, the MTBE problem worsened dramatically. In seven weeks, MTBE concentrations nearly doubled, from 6 parts per billion to 11.8.

Currently, jet skis are not allowed on Anderson or Calero, where two-stroke motors have left a persistent residue of MTBE, which is highly soluble and does not appear to readily biodegrade in the environment. Up to a week ago, 40 jet skis were allowed on Coyote on weekends. The number has since been reduced to 20. But MTBE is only a small part of the jet-ski fallout. Jet skis are causing other, equally severe environmental impacts at Coyote.

SUMMERTIME WATER at Coyote is usually clear, with vegetation and tiny fish visible along the shore. On weekends, however, jet-ski turbulence is causing huge "brown-outs" along the west-side shoreline. From the edge of the water out to 50 yards into the lake, there is zero visibility in jet-ski season. On a recent Sunday, Aug. 8, jet skiers caused an unsightly mud slick all along the shore.

Unlike other boats, jets travel at high speeds in very shallow water, churning up sediment and vegetation in areas normally full of algae, larvae and zooplankton. The Blue Water Network (a division of the Earth Island Institute) is a San Francisco-based coalition of scientists and environmentalists who have studied the long- and short-range effects of jet skis. According to Blue Water president Russell Long, who holds a doctorate in developmental ecology, the jets release petrochemicals that float on the surface microlayer and settle within the shallow ecosystem. The long-legged birds, standing in 6 inches of water, cannot see their food or prey below the surface. Turbidity blocks light penetration, depletes oxygen and harms both fish and birds. In June, two-stroke motors were banned at Lake Tahoe because they contributed to the decline of water clarity in one of the deepest lakes in the world.

Years ago, California's great outdoor writer Tom Stienstra wrote: "Coyote can be the best bass lake in the Bay Area."

How times change. Jet skis have wrecked the joys of fishing at Coyote on weekend days. I saw only two fishing parties take out boats on a recent sunny Sunday. In a lake stocked with trout, no one in either party caught a single fish.

I was also surprised to see lots of jet skiers swimming at Coyote, in the very lanes where other personal watercraft spin, leap, rip and plough. Although swimming--even wading--is prohibited in all drinking-water reservoirs, park rangers told me that the county of Santa Clara now exempts jet skiers from the no-body-contact prohibition.

Water contact is not incidental to jet-ski activity. Diving, falling off their craft, standing in shallow waters, driving jets from down under the water and treading water are all part of the fun. But when jet skiers separate themselves from their craft, their bobbing heads are barely visible as other jet skiers speed by.

It's worth noting that three serious jet-ski accidents have already occurred at Coyote Lake since June, according to Patrick Silva, a calm-voiced park ranger who's worked at Coyote since 1994. Silva processed all three accident reports for the Department of Boating and Waterways. He recalls that one girl was flown out of Coyote on a passenger jet, knocked out and incoherent, with bruising to her brain. He attributes the accidents to "the amount of power, inexperience of riders and lack of control."

THE INTRUSION OF LOUD, high-pitched noise, the destruction and disturbance of wildlife, the pollution of air and water, the high numbers of serious accidents and the seething resentment of nature-seeking visitors are the hallmarks of lakes dominated by personal watercraft. And they are not confined to Coyote or to just a few scattered waterways around the state. The carnival atmosphere has become typical of weekends on most California lakes and estuaries.

The reason is simple: jet skis are tremendously fun to ride. Steering a tiny vehicle at huge speeds over a surface just 6 inches below one's feet is a thrilling experience. Wave-Blasters boast that they can travel from 0 to 50 miles per hour in five seconds.

But recreational use of high-powered machinery is not the problem. Jet skis would be fine in specially created man-made areas or water theme parks, along with roller coasters and bumper cars. It's the degradation of endangered sanctuaries that is causing public dismay. As naturalist Edward Hoagland puts it: "The gluttonies devouring nature are remorseless."

The conflict between high-speed thrill vehicles and the serenity of nature is irreconcilable. The very features that make jet skis popular--their bursts of speed, their zigzags and erratic cuts, their rooster-tail spray, their wave-jumps and ability to zoom over shallow water (where fish spawn and birds nest)--automatically put jet skis in conflict with the low-impact recreation for which our lakes are preserved.

JET SKIS ALSO PRESENT the worst traffic-safety statistics on record for watercraft. In l997 jet skis accounted for 17 percent of all registered boats in the United States but were responsible for 52 percent of all boating injuries. In California, according to the Department of Boating and Waterways, jet skis comprised 16 percent of registered vessels but caused 55 percent of boating injuries. Fifty-seven people died from jet-ski accidents in the U.S. in l997. Seven were Californians. Two teenagers were killed by jets on Lake Sonoma. On Fourth of July weekend last month, in completely separate incidents, two youths were killed on jet skis in the Delta near Stockton.

It's no wonder. The new Kawasaki models, like the Ultra-150, hit 65.5 miles per hour on the radar gun. They ride faster than automobiles on expressways, yet jet skis have no brakes, and when the rider "throttles down," steering capacity dies. The U.S. Coast Guard exempts personal watercraft from basic standards that other boats are required to meet.

And water isn't the only medium in which jet-ski motors produce dangers. According to the California Air Resources Board, a single jet ski emits more pollution in two hours than a passenger car puts out in a year. The current two-stroke engines spew 25 percent of their fuel unburned into the water and air. That's about three gallons per hour. Dr. Long of the Earth Island Institute notes that "in lakes that retain water for a long time, it is virtually impossible to ever get these toxic chemicals fully removed."

In apparent defiance of all these facts, manufacturer advertisements reflect open contempt for the environment. Celebrating a water-churning jet, one Polaris poster reads: "It's enough to make webbed toes curl." As if to defy the tread-lightly-and-leave-no-trace wilderness ethic, a Tigershark poster reads: "Leave a streak on the glass."

MANY CALIFORNIANS appreciate the beauty of nature and respect the right of others to enjoy lagoons, estuaries and waterways in peace. Whether they are backpackers, bird watchers, swimmers, fishermen or campers, they use our lakes in unobtrusive ways. They visit these spots to escape the noise and stress of everyday lives.

In l998 the National Park Service, mandated to leave our great parks "unimpaired for the enjoyment of future generations," debated regulations that would prohibit jet-ski use in 75 percent of the national park system.

According to a l998 Colorado State University poll, 92 percent of Americans support prohibiting or severely restricting personal watercraft in national parks. In response to public outcries against personal watercraft, Olympic National Park, Glacier National Park, Golden Gate National Recreation Area and Grand Canyon National Park, among others, banned jet-ski use. Conflicts over jet skis have been resolved in world-renowned sanctuaries: the magnificent San Juan Islands in Washington, the mysterious Florida Everglades, the life-sustaining waters around the Farallon Islands.

But only a few California counties and cities have passed ordinances that ban jet-ski use in local waters. To prevent accidents, the city of Pacifica banned jet-ski use in its five-mile-long surf zone. To protect sea otters, jet skis are banned in the Monterey Bay Sanctuary. Two-stroke engines, notorious for water pollution, are now banned on Lake Tahoe.

Notwithstanding these disparate environmental victories, the jet-ski industry is winning the ongoing war for domination and commercialization of California's 373 recreation lakes and waterways. No accessible lagoon, river, seashore or lake seems sovereign anymore.

In California Fishing, writer/outdoorsman Tom Stienstra comments on the rising cacophony on California recreation lakes: "skiers taking over" Lake San Antonio in the summer in Monterey County; "self-obsessed water-skiers ripping up and down the lake during the summer with little regard for anything but themselves" on Lake Berryessa.

The pattern is typical all over California. Jet skiers don't share the water; they conquer it. As the Kawasaki slogan puts it: "Own the water!" The pollution, the noise, the hazards all drive kayakers, fishermen and hikers--"those who turn to the wilderness to find solace and serenity"--away from the water by 9am on weekends.

What an ironic comment on federal, state and county environmental policies when Californians are forced to leave the wilderness in search of peace and quiet.

It was not until the early '80s, when the Reagan administration made wilderness areas available for commercial exploitation, that jet skis first appeared on public waters. Today personal watercraft account for one-third of all boat sales.

Kawasaki's Ultra-150 costs $8,000, and its advertisements feature the allure of speed and power. New jet-ski models are bigger and faster than the old models. The Polaris Genesis carries three passengers and holds 600 pounds. The new X-145 from Polaris Industries is a three-seater with 135 horsepower. Polaris produces jet skis with attitude. One Polaris poster reads: "Thumb your throttle at the world!"

IN ANY LANDSCAPE, it is the water that captures our attention--roiled waves crashing on the cathedrals of the Pacific, rushing water in woodland creeks and streams. Water is almost hypnotic. Our lakes are drinking fountains for deer and raccoon, forage areas for frogs and amphibians, habitat for water bugs and minnows that hunt for insect larvae. Even for humble human visitors, water is a world that calms our spirits.

It's true that most of our accessible lakes, lagoons, reservoirs and rivers--even our offshore islands--are not pure wilderness. There is drive-up access to marinas, and hundreds of lakes are located near major highways. Nevertheless, under careful and enlightened administration, California's backyard wilderness could still provide a genuine--and needed--respite from the din of modern life.

Many of our lakes and reservoirs are set in virgin forests, along mighty rivers like the Eel and the Smith. In the early dawn, when mists sit on silent haunches--long before the motors are fueled--our lakes are still wonders to behold. In their naturalness they inspire reverence and humility. And wild animals do share the wilderness with Homo sapiens if only we respect the zoning laws of nature.

The jet-ski conflict, then, is not a matter of fixing up technology. A better, more "fuel-efficient" jet ski in the wilderness is not the answer. And no quick fix by Arctic Cat, Bombardier, Polaris, Kawasaki and Yamaha will overcome the mess.

Nor is the conflict a playland issue. In its essence it is a wilderness issue. You either respect our wilderness heritage, and respect the right of citizens who pay for it to enjoy its solace, or you don't. Conservation is the precondition of legitimate nature recreation.

Lao Tze writes that "some men go fishing when it is not fish that they are after." Next week I'm hiking back to the Coe wilderness, heading out to Mississippi Lake, where you can hook bass on every cast.

Every time I get out my compass, pack a few quarts of water, my friends warn me about rattlesnakes and mountain lions in this off-the-beaten-path wilderness.

This is no big deal. If I get killed by a mountain lion, at least I'll die with dignity. It's those industrial accidents in the wilderness (like six jet-ski deaths on Tahoe in l995) that are degrading. For me, hiking in Coe Park is a way of playing it safe. At least I won't get killed by a floating chain saw at sunset.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Photographs by Christopher Gardner

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Photograph by Christopher Gardner

Paul Rockwell is a librarian and writer in the Bay Area.

From the September 2-8, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.