![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Avant-Godard

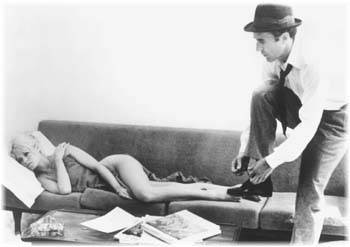

Nude Descended to a Sofa: A troubled couple (Michel Piccoli and Brigitte Bardot) share furniture but little else in 'Contempt.' Jean-Luc Godard's 'Contempt' brought the French New Wave's brains face to face with Brigitte Bardot's beauty and the temptations of wide-screen success IN THE BEGINNING of Contempt, Jean-Luc Godard's 1963 touchstone of French New Wave cinema, Brigitte Bardot is exposed to the camera in a variety of cheesecake poses, her magnificent golden rump framed by a kitschy plush white rug. Bardot lies on her bare stomach, asking her husband (and the viewers), in that maddeningly flat voice of hers, which part of her body is the best. The ankles "Do you love them? You do? How about the knees?"--and so forth up her body--"Do you like the breasts or the tips better?"--while Georges Delerue's music rumbles threateningly like a thunderstorm. Bardot parcels herself out like those posters of a steer that used to hang on the wall at the butcher's shop, with the dotted lines explaining which portion is rump and which part is brisket. The sequence was director Godard's reply to a producer who demanded to see more of Bardot's ass, since the rights to photograph said butt had cost, it is rumored, half of the film's 5-million-franc budget. Godard shot the scene through red and blue filters that obscure exactly what he was being urged to sell. That guerrilla tactic sums up this rarely screened classic: an act of sabotage occasioned by a story about selling out. The restored Contempt, which hasn't been visible in a good print for at least 10 years, is more than just one of the key works in the extensive oeuvre of Jean-Luc Godard, the Swiss mastermind of the French New Wave. Contempt is an experiment that turns the whole idea of movies inside out. Contempt reverses the idea of love at first sight--that ideal that's sold so many movie tickets and blighted so many lives. Godard demonstrates that one insignificant gesture, one momentary lapse of attention, can cause the woman you love to become completely indifferent to you. Contempt upends the familiar notions of showmanship by turning the wide-screen camera around and pointing it straight at the audience. Godard doesn't want to seduce us with the magic of movies; he intends to portray a degrading commercial enterprise that befouls what it touches. Without making women into poor little martyrs, Contempt deconstructs the use of sex as a lure to hook audiences. One of the characters, an elderly director (played by the great German director Fritz Lang), sums up the movie vision of women: "Show them a camera, and they'll show you their ass." Before feminist critiques of the movies became common, Godard made an early and memorable attack on the sexism of the movies. And later, the absolute mulishness of Bardot's character earns Godard's grudging respect. It's not Bardot whom Godard hates, but Bardotism: the packaging and sexual exploitation of a woman. Bardotism is a metaphor for the packaging and exploitation of any talent, especially his own. Godard once said, "I am a whore fighting the pimps of cinema," and none of his films expresses that dilemma more starkly than Contempt.

THE RICH NEW 35MM print of Contempt is being presented by Martin Scorsese, returning the favor after having borrowed some of Delerue's music for his Casino soundtrack. The film is a reminder of the almost-forgotten French New Wave, a short-lived but exciting period when a handful of young directors using every intellectual tool they possessed tearing apart the accepted notions of what cinema could and should be. The movement took off in 1959 with Godard's fast, cheap homage to American noir, Breathless; François Truffaut's The 400 Blows; and Alain Resnais' Hiroshima Mon Amour. When it was understood that these French New Wave filmmakers--Godard, Truffaut, Resnais, Eric Rohmer, Louis Malle, Claude Chabrol and a few others--were the vanguard, were "hot," the money and the stars inexorably followed. Contempt, shot in expensive locations and made in color and wide-screen "Franscope" (French Cinemascope), shows us Godard caught in the machinery of movie financing, on the cusp of co-optation. The tensions behind the scenes are deliberately reflected in the scenes. Contempt is a natural introduction to Godard's sometimes formidable work. The film boasts a linear plot, outstanding color photography by Raoul Coutard and, of course, the golden pelt and feline face of Bardot. Michel Piccoli plays Paul Javel, a French playwright in Rome, paying the bills with some hack screenwriting. A crass producer, Jeremiah Prokosch (Jack Palance), solicits him for a scripting job. The writer and the producer meet at Cinecittà, the vast Italian film studio that was then just another Roman ruin--there's every sign of neglect but tumbleweeds in the streets. Because of the seating arrangement in the car on the way to Prokosch's villa for a conference, Paul's wife, Camille (Bardot), mistakenly believes that her body is part of the contract between Prokosch and Javal. Camille's anger toward her husband for leaving her alone with Prokosch deepens--not so much because she is concerned about his artistic integrity, but because she senses that Javal is being taken over by Prokosch without even putting up a fight. Prokosch wants to make a film version of The Odyssey. The almost inevitable cheapness of Contempt's film within a film is signaled to us by the way Prokosch bares his yellow, apparently filed teeth, practically ejaculating over the rushes of a few half-clad nymphs bobbing in the ocean.

The best of Godard can be found on video. A Godard fan page. Lots of Godard links. A recent brief interview with Godard about film and politics. Godard filmography.

In the Prokosch version, the epic poem is the story of a wanderer who left home because he wasn't getting along with his wife. A weary, monocled German director named Fritz Lang (Lang himself) is in the hire of Prokosch. He's the moral center of the film, since he sees Prokosch for the vulgarian he is. Lang works for Prokosch, but he won't drink with him. Lang tries to pass on to the younger man the point that making one more bad movie isn't going to end Western civilization. Camille and Paul begin to drift apart, stalemated by one of the screen's most ghastly marital tiffs. He looks like a man haplessly trying to cheer up a sulking pet tiger. Finally, Paul invites/pressures/wheedles her into coming along with him to Prokosch's isolated villa on the Mediterranean island of Capri. There, Prokosch moves in to seduce the estranged Camille. Contempt's settings are simple and bare: a little apartment, a small movie theater and, finally, a modernistic bunker with picture windows, wedged into a stony cliff on Capri. The place is topped with a distressingly oversized sun deck. (When Bardot sunbathes on this uninviting deck--nude, of course--she looks like a shrimp lost on an acre of asphalt.) The formula is simple: A affects B, which affects C. And yet there is an enormous amount left for the viewer to guess at and suppose. It is necessary to judge people, motives and silences in order to understand why it is that nothing can clear the air between the hopelessly estranged couple. Camille might be not just a wife but a symbol--she might represent the muselike impact American film had on Godard when he was a young, rabid fan of Hollywood movies. Godard once said (and I wish Steven Spielberg had read this), "As soon as you can make films, you can no longer make films like the ones that made you want to make them." Despite its cool, gleaming surface, Contempt isn't slick; in fact it's fairly raw at times. Indeed, the long Big Snit sequence between Paul and Camille is almost unwatchable--too close to those late-night fights with a lover everyone must have suffered through. The spat is like one of those fights in which it seems like language itself is breaking down. Every tentative complaint, every conciliatory phrase, has to be withdrawn, examined, re-examined and apologized for. Critic David Thomson suggests that Contempt is a divorce movie, about the upcoming separation between Godard and his wife and frequently used leading actress, Anna Karina. (The two eventually divorced in 1967.) Still, the essence of the story can be found in the novel it was based on. Although Godard has derided the source book as corny, he followed the basic narrative of Alberto Moravia's Il Disprezzo (A Ghost at Noon) more than he veered away from it.

The same incident triggers both book and movie. In seating his wife in the producer's car for the trip to the villa, the screenwriter closes the car door "with the decided gesture of one who closes the door on the safe." Molteni [Paul in the movie] is, like Godard, an exfilm critic and screenwriter, and in a particularly telling passage, he explains the position of the writer on a movie (in a word, "prone"):

Deep-Dish Movies GODARD WAS A collector of different film forms and ideas, and in his prime, in the '60s, he had incomparable energy, spilling all of his influences out in a cascade. He flooded the screen not just with primary colors; flat, pure landscapes; and the harsh lights of cities but also with images of paintings (Klee, Velázquez, Rembrandt); title cards; narrators who address the audience; shards of sound at war with images; and quotations from other films and from novels, histories and satires. (If you came to Godard via Monty Python, you're already well prepared for the French director.) While Godard is as brainy a director as ever got involved in a dumb proposition like the movies, he's not a brain-in-a-jar type. Even as a world-famous ironist, Godard was willing to make a fool out of himself with his passions and his jokes. His movies are fun to watch; some are hilarious, and almost all are enlightening. It's a loss not seeing Godard's wide-screen works in a theater, and Contempt demands to be seen on the big screen. Still, there's an advantage to viewing his films on tape. Watching Godard on VCR--as you basically have to, if you want to see him at all--also means being able to replay the more elusive passages in his work. Manny Farber, ordinarily Mr. Knuckle Sandwich in his taste in films and in the cruelty of his reviews, put it best: "No other filmmaker has made me feel so consistently like a stupid ass." The phrase "deep-dish" is used to describe anything beyond the superficial in the movies. It turns up in the vocabulary of both critics and filmmakers. "Deep-dish" was even coined by a recognized Hollywood genius, Preston Sturges. In Sullivan's Travels, the hero is busy filming an inept piece of social commentary that is derided by a wiser producer: "There's nothing like a deep-dish movie to drive an audience out into the open." That's the truth--moreover, that's funny. But deep-dish cinema is only a failure when it's inept. Fritz Lang, in addition to being a sharp, facile entertainer, was also a brilliant political film director. By using him as a character in Contempt, Godard acknowledges that Lang's impressionist visions of the evils of the workplace (Metropolis) and of revenge fantasies (Fury and M) have poetry and terror. Fury is a statement about lynching, but people who see that mob heading out to burn Spencer Tracy alive in his jail cell never think "deep-dish."

True, Godard's films include hours of deliberate dullness, self-indulgence and obscurantism. More than once, the cardboard characters in Weekend lecture the audience at numbing length on the rise of the proletariat and the withering away of the capitalist state. John Waters answered this complaint in a essay on Godard's 1986 antiCatholic Church scandal, Hail Mary!: "As in most Godard films, half the time I had no idea what was going on; something I wish I could say about many Hollywood films." Meanwhile, fans looking for depth peer at big-budget films for traces of some sort of social or political comment, as once upon a time they might have looked for a flash of nudity (of course, Godard delivers both). Moviegoers are led to believe that 187 is a serious analysis of gang violence; they see feminist empowerment in G.I. Jane--a '90s version of the type of soft-core porn film once known as a "roughie," in which the heroine was not only undressed but beaten up a lot. Except for the as-always-struggling makers of documentaries, today's independent films are nearly mute on the subject of greed and economic inequality and are made by people with little hope of social change. All too often, films are crafted by artists unwilling to argue with material success and terrified of biting the hand that feeds them. It's as if filmmakers were afraid to take a political stance at the risk of alienating audiences. Such reluctance renders Contempt's study of moral osteoporosis all the more current. Cycles of Cinema NINETEEN ninety-seven was the year that Godard (with his newest project, Histoire(s) du Cinema (parts 3A and 4A), couldn't draw a crowd at Cannes. Luc Besson by contrast was mobbed, thanks to this year's model Bardot, Milla Jovovich, whose body was unwrapped to keep people watching The Fifth Element. As hackneyed as The Fifth Element is, Besson did learn from Godard, whose classic Alphaville has the same motif as this summer's French hit. Both films feature sleazy ex-Marine types--Alphaville's Eddie Constantine and The Fifth Element's Bruce Willis--as men who outwit technocracy with their faith in the concept of love. Young filmmakers build on old filmmakers' ideas, and the old filmmakers thus look less relevant, as if the child actually had fathered the man. Godard is becoming a more vague and peripheral figure as the years go by, since his main concern, the conscience of man under capitalism, seems immaterial to many modern film students.

All that's left are echoes of Godard's era. That major actor of the French New Wave Jean-Pierre Léaud (Truffaut's constant star, and the lead in Godard's Masculin Feminine) turns up this summer as the sequestered, broken-down director in Irma Vep, a whore who doesn't have the heart to turn that one final trick. Léaud's character is the victim of a French cinema dominated by the model of the American action films, dumped on the international market just like cartons of cigarettes. There must be more than a few movie fans overseas like the ignorant journalist in Irma Vep who reveres Jean-Claude Van Damme and believes that too many intellectuals drove away the French audience--and who also believes that what's needed to bring them back is more violence, more sensation. The word "decay" is inevitable when writing about films over the course of decades. One history is titled The 50-Year Decline and Fall of Hollywood. Still, even half a century ago (Sunset Boulevard was made in 1950), the movies were considered to be ancient, corrupt and played out. Farther back, even as early as the beginning of sound, there was talk of the movies being washed up. So it's important not to consider any current decline in the quality of current films as the sign of an irrevocable slump. Good Hollywood movies will most likely come again someday, and French film will survive The Fifth Element, just as it survived Cousin, Cousine 20 years ago. Still, it's depressing to see the French film industry serving as a test market for America--a vat where the source movies for Three Men and a Baby, The Associate and Jungle 2 Jungle are concocted--and a dumping ground for our own screen swill. Artistic epochs seem to be either great periods of discovery or great periods of retrieval, and after viewing the screen products of the past summer (the worst box office in five years), I'd suggest this is one of the latter. So it's exciting to rediscover the freshness of Godard, Contempt and an era when cinema that acted not as a narcotic, but as a stimulant. The sordidness and dumbness of the sort of movies that Godard was griping about when he made Contempt are just as sordid and dumb as ever. And it is a testament to his character that Godard never succumbed to the lure of easy money. The kind of movies he made are still worth making, worth talking about, worth fighting over--and worth seeing.

Contempt (1963; 105 min.), directed by Jean-Luc Godard, adapted by Godard from Alberto Moravia's novel, photographed by Raoul Coutard and starring Brigitte Bardot, Jack Palance, Fritz Lang and Michel Piccoli. [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.