![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Life After Death

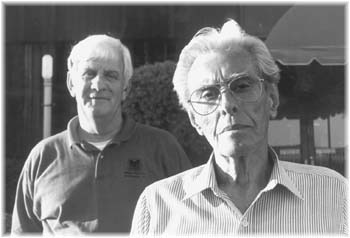

Robert Scheer Organ-izers: Robert Cardenas (front), a liver transplant recipient, offers support to those like Jerry Kelly, who is on the waiting list for a liver. Many people who need organ transplants will die waiting for donors, some of whom are scared off by myths about body-part-harvesting By Kelly Luker FOR A POPULACE that has made a religion of recycling, the citizens of the Santa Clara Valley are not thinking locally enough. While being careful to separate the green glass from the brown glass, they are ignoring wasteful behavior closer to home--taking perfectly good body organs with them to the grave when they die. This is a serious problem for some local residents. They are children with congenital diseases that slowly destroy their tiny kidneys. They are junkies and drunks who belatedly discover that the 12 Steps may save their souls, but recovery is too late for their cirrhosis-laced livers. They are homemakers with failing lungs, business-owners with diseased hearts, teachers and students whose lives intertwine around one shared need--a healthy, used organ. The wait is often long--for about 2,500 people around the country this year, the wait will be too long. They will die waiting while the heart, lung or liver that could have saved them is buried or cremated with its original owner. In an area that preaches conservation of everything from the mud-wallowing gobi to the long-toed salamander, how can such wanton waste of valuable resources be explained? Chalk it up to a lack of education, and people's innate ability to turn a blind eye (actually, a perfectly good eye) to the Grim Reaper. It's the third Wednesday of the month, and Jerry Kelly is setting up chairs in the community meeting room at Santa Cruz's Dominican Hospital. A tall guy in Bermuda shorts, Kelly looks like he'd be more at home on a golf course than waiting to greet new and returning members of the support group that he organized back in September. Kelly's ruddy good looks and healthy glow give no clue that his liver is heading south, the loser in a 30-year battle with a slow-moving disease called hepatitis C. He is now on the waiting list at the medical center of the University of California, San Francisco, for a new liver. Although some of those who show up tonight contracted the virus through intravenous drug use (and for that reason do not want their names used), Kelly says he does not know how he got hepatitis C. As someone who never stuck a needle in his arm and hasn't had a drink in almost 30 years, Kelly did not even know he had a problem until gallstone surgery revealed a liver riddled with cirrhosis. He was then given the news that he needed a transplant. "I was certainly frightened when I first found out," Kelly says. "I was frightened more than anything of getting debilitated and dependent. That scares me more than anything."

Myths, questions and one urban legend about organ donation.

Achy-Breaky Hearts KELLY ISN'T ALONE in his fear of the idea of an organ transplant. As a potential recipient, he has specific, but they reflect the general population's queasiness and ignorance about trading out body parts, probably bred from a steady diet of Chicago Hope, Geraldo, urban legends and 30-second sound bites. Tabloid shows have convinced many Americans that their eyeballs and lungs will be ripped from them before they're officially dead and that they will wake up, blind and extremely short of breath. Others express a slightly more reasonable fear: that by giving that last gift of life, they will blow the opportunity for an open-casket sendoff. Many are convinced that a chronic disease--diabetes, cancer or AIDS--would rule them out as potential donors. According to the Richmond, Virginiabased United Network of Organ Sharing (UNOS)--which coordinates donors and recipients through the nation's 62 organ donor centers--there are many myths which keep people from putting a mark in the little organ-donor circle on the front of their driver's license. (See sidebar.) But beyond the fear or ignorance that prevents most people from donating their organs, experts say the biggest impediment is a conversation that doesn't happen. "People believe if they have a donor dot on their license, that's sufficient," says Phyllis Weber, executive director of the California Transplant Donor Network. "But the family must give consent." Although a potential donor may have the best of intentions, that healthy heart and pink liver may well accompany him or her into the ground unless the next of kin knows their final wishes. Since death (at least to owners of young, healthy organs) has a way of coming suddenly and unpredictably, the subject of "harvesting" can be understandably awkward with grief-stricken relatives. Although the world of organ donation is rife with fallacies, the process of who gets what--and when--was recently revealed to have its own problems in an exhaustive study in the pages of the Cleveland Plain Dealer. The Plain Dealer's months-long investigation revealed that healthy and usable hearts were turned down by transplant hospitals because they did not have the personnel available at the time. Patients waiting for a heart at those hospitals were never informed of their near-miss. One hospital even ceased doing heart transplants altogether, then failed to inform critically ill patients waiting for a heart. In that case, two died as a result. The Plain Dealer also discovered that waiting times for organ transplants can vary widely by region and hospitals, yet doctors rarely told their patients this crucial information. For example, Kelly would probably have a waiting time of eight days for a new liver if he chose Tulane Hospital in New Orleans. California-Pacific in San Francisco, one of the three major liver transplant centers used locally, has a median waiting time of 473 days. Although he has become an expert on both hepatitis C and liver transplantation, Kelly says he was not aware of this.

Good Medicine: Kidney recipient Amanda Olivo (center) shows some of her medication--which she says smells like skunk--to best friend Franchesco Schaaf, while mom Lisa Olivo looks on. A Whole Life UNOS has stymied further investigation by refusing to release 1995 and 1996 records to reporters--and even the federal government--that would reveal just how many healthy organs are being turned away. The fighting between bureaucrats and reporters is a world away from Amanda Olivo, a stunningly well-spoken local 13-year-old. An avid tap, jazz and ballet dancer, Amanda lives with the hopes, dreams and disappointments common to all young girls on the cusp of womanhood. The fact that she lives at all is thanks to the generosity of the parents of an 8-year-old boy who died in a car accident. Born with nephrotic syndrome, Amanda began having kidney complications when she was 4 years old. By 8, she was on dialysis. "It was a lonely time, because I couldn't spend the night with my friends," says Amanda. "I didn't have the typical kid life. It was hard, but my parents got me through it." As did her best friends Franchesca Schaaf and Amy Hamblin. When other kids--particularly boys--would give Amanda a hard time, she says, Franchesca always found the right thing to say. "She'd remind me of the positive things, or she'd just laugh and say, 'Men are pigs,' " grins Amanda. Since her kidney transplant about five years ago, Amanda says, "I find myself having a lot more energy. Without it, I wouldn't be able to do my four hours of dance a week." This past winter, Amanda debuted onstage as a snowflake in The Nutcracker. Like Amanda, Bill Rainford cherishes the life that has been given back to him. The Episcopal priest received a heart transplant 11 years ago after a sudden and near-fatal virus attacked his heart muscle. His heart stopped several times as doctors feverishly worked to stabilize him long enough to proceed with the transplant. Today, the Rev. Rainford works--in lectures and from the pulpit--to educate people on the importance of organ donation. Rainford reports that after one seminar, a doctor told him that he never recommended organ transplants because, in the doctor's words, "I've never seen any good quality of life following a transplant." Indeed, Rainford's regimen of immuno-suppressants has created other health problems. He reports that he is preleukemic, his kidneys are failing, his lungs are scarred and he has developed osteoporosis--all the result of medications following the transplant. But those problems don't outweigh what he says he has been given in the last decade. "I now know that I'm totally loved by God and that death is not to be feared," says the priest. And then there is life. "I've had time with my wife and children. I've been able to watch 10 new grandchildren come into the world," he says. "And I've been able to help others find what's meaningful for them. I learned that it's all a gift." [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.