![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

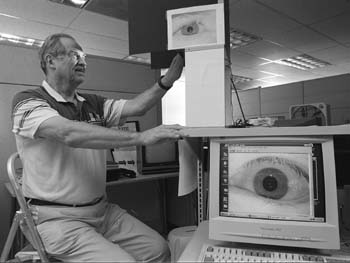

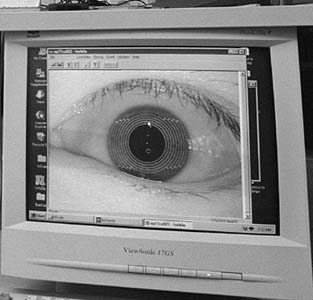

Larry Brazil Myths of Fingerprints: Researchers say biometrics is really less revealing about data that matters than using a grocery store discount card. Digital Persona The Department of Defense is funding biometric research at San Jose State University. Soon, fingerprint, face and iris scans will replace passwords at the ATM and credit cards at the local grocery store By Holly Hanke 'NOW, THAT'S A PRETTY GOOD-looking fingerprint," says Tan Tran, pointing to the image he has just called up on the computer screen in front of him. I look at the seemingly infinite loops that ring the pad of my right index finger, loops which distinguish me from billions of others on this planet in a way that physical characteristics like my brown hair or green eyes can never do. The whole process of capturing my print had taken mere seconds: just a tap on a glass sensor encased in a mouse-sized beige metal box, and I, or at least a few distinctive points of my fingerprint, was filed away in the computer. Once the stuff of science fiction and fodder for recent movies like Gattaca and Enemy of the State, fingerprint and voice recognition, facial imaging, hand geometry, iris-scanning and signature verification systems may someday become as ubiquitous and indispensable as the neighborhood ATM. But while these so-called biometric systems do have the potential to streamline security and ease our password-burdened lives, important questions about who owns and has access to biometric data are going unanswered. The bank of five computers that Tran oversees on the fourth floor of the engineering building at San Jose State University is not an ordinary computer science classroom. It is the headquarters of the National Biometric Test Center, a Department of Defense-funded project where government agencies like the Immigration and Naturalization Service and state welfare departments can come for guidance on selecting the biometric system most suited to their needs, whether it's for border control or cutting down on social services fraud. The fingerprint is just one type of biometric data being used at the center. Trueface, an $8,000 system that recognizes defining facial characteristics, protects Room 494 at the center. When I walk up to the room and type the correct access code, two spider-eye-like cameras embedded in the keypad take my picture and compare it to file photos of authorized users. Iriscan, a $5,000 system, scans the iris with an electronic green eye inside a darkened window. No match; no access. The toaster-sized unit could be mounted on a wall outside, say, a prison door. Blanket Security IT USED TO BE that federal law enforcement agencies like the FBI and a select few classified government installations (like Lawrence Livermore Labs) were the only institutions using biometrics. The cost for even a single system was, for most agencies, prohibitively expensive. But in recent years, with lower manufacturing costs and a growing concern about computer network security breaches and credit and social services fraud, more federal agencies and state governments have turned to biometrics for help in combating security problems. Already, eight states (Arizona, California, Connecticut, Illinois, Massachusetts, New York, New Jersey and Texas) are using automated fingerprint identification systems to track welfare recipients, and three others (Florida, North Carolina and Pennsylvania) have systems pending. The Department of Motor Vehicles in California, Colorado, Georgia, Hawaii and Texas requires fingerprinting for driver's licenses; the INS uses a combination of voice, face, hand and fingerprint recognition technologies for border control; and the Federal Highway Administration is considering implementing a fingerprint-based system to track driving violations of interstate truckers. In the private sector, biometrics are finding homes in some unusual places. Season pass-holders at Walt Disney World now use a two-finger geometry reader to enter the park. Employees of United and Hawaiian Airlines use a similar system to check time and attendance. High-powered rifles used by biathletes at the Nagano Winter Olympics were linked to their user with an iris scan. Even the Kroger grocery chain is experimenting with a "touch and go" fingerprint-based check authorization system. And as electronic commerce takes center stage, vendors are banking on biometrics to improve the security of online transactions. No Secrets ONE OF THE MOST outspoken proponents of biometrics is Jim Wayman, the 47-year-old director of the National Biometric Test Center. An odd cross between an aging surfer ("I took second place in my heat in the Carmel surfing contest last summer," he writes in a gleeful email) and a blue-blazered government employee, Wayman is possessed by an almost missionary zeal when addressing the topic of biometrics. "I want to be the guy who makes up all the rules. Does that make me--what's the word--a megalomaniac?" he says as he leans back in his chair and clasps his hands behind his head. The Department of Defense, his boss, has just told him that it wants the center to play a bigger role in helping define technical standards for biometrics technologies as the industry matures. It is a role Wayman welcomes. "I love being the center of attention," he says. To illustrate why he believes biometrics are the key to a more secure future, he jumps up and walks over to a white board leaning against one wall in his tiny windowless office. "OK," he says. "Give me your credit card number." I demur. "You see? You wouldn't dream of giving it to me." But you already give it away every time you swipe it to pay for groceries or gas or type the numbers into a computer to buy something online. And your Social Security and credit card numbers are far more likely to be used in a damaging way than a fingerprint template, he argues. "Your privacy may be threatened, but it's threatened now," he says. "The addition of biometric information is not going to be a further threat to your privacy." Wayman's impatience with what he considers misconceptions about biometrics is a recurring theme in his presentations to audiences around the country. "I've even posted my fingerprint biometric on my website," he says. "I don't care who sees it."

Blind Data IT'S EASY ENOUGH to conjure up visions of a biometrics-based Orwellian dystopia and ignore the privacy-enhancing capabilities of the technology. But conspiracy theories aside, the fact remains that there are currently no controls over how biometric data are used, a problem that raises a number of troubling privacy issues. Beth Givens, director of the Privacy Rights Clearinghouse, is worried about the potential for the establishment of a centralized database of everyone's biometric information. "I'm going to sound like a raging paranoid," she says from her office in San Diego, "but let's imagine we are living in a time of political conflict. It is not unforeseeable that biometrics could be used as a form of social control. For example, law enforcement could make a videotape of a demonstration and, using faceprint technology, identify who was protesting." While Givens' apocalyptic scenario is extreme, sharing of biometric data is already happening. Fingerprint-based biometric information stored in INS databases can be accessed by Customs and the FBI, and the social welfare agencies of Connecticut, New York and New Jersey are linked to prevent welfare recipients from receiving benefits in more than one state. Other privacy experts sound a less ominous warning, but nevertheless point out a basic problem with the way this technology is being pitched. Phil Agre, an associate professor of communications at the University of California-San Diego, says that while biometrics may be part of a response to 21st-century security problems, companies that market the systems as "privacy-enhancing" are telling a story that is too simple, and they don't appear to be interested in the larger issues at stake. "The problem is that the conceptual terrain is unmapped," he says. Roger Clarke is an Australian professor who studies the public policy implications of the use of technology in government, and he is credited by some as the first to use the term "digital persona" to describe the personal information about an individual that resides in cyberspace. In an email exchange Clarke is cautious, but not dismissive of biometrics. "Frankly, I'm not terrified of such technologies," he writes, "just of the really dumb ways that most organizations will try to use them. The degree of threat depends entirely on how it gets applied." Privacy organizations are "a problem" for the industry, says analyst Erik Bowman, who notes that biometrics vendors recently formed the International Biometric Industry Association to educate the public about the technology and to lobby against what they perceive as harmful legislation. In California, Kevin Murray (D-Los Angeles) is sponsoring a bill that is one of the first attempts in the country to regulate the use of biometric data. Objections to two of the bill's provisions were raised. A civil penalty of $5,000 for the unlawful use of biometrics information was deemed too high by the Assembly ("Can you believe that?" says Givens, who thought the penalty too low). And confusion over the technicalities of a clause calling for the destruction of original biometric images stalled the bill in the judiciary committee this year. However, Stacy Dwelly, a legislative consultant to Murray, says the bill will be reconsidered in January. Card-Carrying Believers JIM WAYMAN took his biometrics road show to a group of executives he believed would be receptive--the National Credit Union Conference on Technology in San Francisco. In a chandeliered conference room, in front of about a hundred credit union directors from around the country, Wayman launched into his spiel: "I've got in my pocket here my INSPASS card," he says, pulling out a laminated card from his wallet with a flourish and holding it up for everyone to see. The INSPASS system, which stands for Immigration and Naturalization Service Passenger Accelerated Service System, is installed at six airports around the country, including San Francisco International. "What this card allows me to do is to go to a special line at the airport where I don't have to show my passport to a passport inspector. I go to a passport machine and present my hand geometry. "The INS loves this system because it cuts down on the number of inspectors they need. I love it because it's free, and I can walk right in. I love that!" he says. "Where can I get one of those?" a man in the back of the room calls out, as if on cue. The whole talk is suddenly beginning to feel like a giant infomercial, as Wayman keeps the group enthralled with his rapid-fire dialogue, expansive hand gestures and "I'm giving it to you straight" routine. As his time draws to a close, Wayman makes a distinction between privacy--"the right to be left alone"--and anonymity. "I don't think there has ever been an established right to anonymity in our society. Biometrics may take away anonymity, but it doesn't take away privacy." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the September 9-15, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.