![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

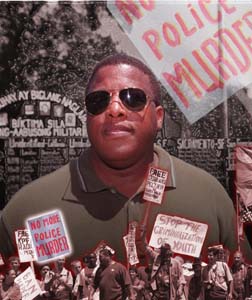

Christopher Gardner Watching the Detectives Can a community and its police force work together to weed out bad cops and improve public safety? Activist Darryl Williams, head of the Citizens Tribunal, is working to bring civilian oversight to San Jose. By Jim Rendon SWEAT DRIPS DOWN DARRYL WILLIAMS' FACE and around his aviator-style sunglasses as he hustles alongside a line of protesters carrying banners and jabbing at the sky with hand-painted signs. A smiling young man is pictured on one sign captioned with the words: "Richard Rosenberg, 1963-1999." "Shot dead by police in his own yard," his father says. A short young man with a shaved head holds up another placard with a directive: "Chief Lansdowne, Terminate Officer Reichert." Williams moves past the signs with his arms out as if trying to corral the entire group. "Please move over, stay on the sidewalk. You need to move over," he chides again and again, to little effect. The block-long group lurches forward and slows down, flows off the sidewalk and back on, trying to find its stride, like a newly hatched caterpillar learning to pick its way along a prickly forest floor. A line of police officers, on motorcycles or well-equipped mountain bikes, rolls along with the protesters. "Bad Cop, No Donut! Bad Cop, No Donut!" one marcher shouts through the screech of the megaphone. One officer smiles. Williams, a husky African American, fills the gap between the two groups, focused intently on keeping the protesters away from cops, enforcing the rules so the police don't have to. "The police cover up brutality. We're tired of officers doing dirty stuff and the district attorney working with them to cover it up. They turn the victim into the perpetrator," Williams says, stacking his allegations one atop the other in a surprisingly matter-of-fact tone. As he talks, he mentions case after case that he has investigated that he says shows patterns of police brutality, harassment, district attorney misconduct, judicial bias and sometimes hard-to-believe abuses throughout the county's criminal justice system. Two years ago, no one but friends and family had heard of Darryl Williams. Today, the longtime San Jose resident is routinely contacted as a source in police misconduct stories. TV news stations are showing up at the events sponsored by the Citizens Tribunal, the group he directs. Williams regularly stops by San Jose Police Chief Bill Lansdowne's office on Mission Street. District Attorney George Kennedy has met with Williams in the tiny nook that houses the local NAACP. City attorney Joan Gallo, county counsel Ann Ravel and San Jose City Council members have also met privately with Williams. He met with the FBI and is scheduled to sit down with Attorney General Bill Lockyer this month. Williams is well aware that in the past two decades, similar attempts in San Jose have failed or gone largely ignored. An organized drive for civilian review of police misconduct cases was quashed in 1993, when the city hired an independent police auditor to coordinate and monitor cases. Activists were so enraged by this compromise that a protest after the council's decision led to 24 arrests. Just last year, the county-appointed Human Rights Commission also recommended that the city create a civilian board to work in tandem with the police department's own Professional Standards and Conduct Unit. Nothing came of it. As leader of the Citizens Tribunal, Williams works with some of these longtime cop-watchers as well as with members of the disbanded civil grand jury. Moving forward on the work that was laid down before him, Williams says he is not going away until things change. And for the first time, it actually looks as if they might. The group has what, on paper, looks like a simple request: that the department fire rogue cops and that the district attorney's office prosecute them when they have broken the law. Williams and others believe the problems have endured because police are allowed to investigate themselves without public or media scrutiny and because of too-cozy relationships among the police, prosecutors and judges. Williams pulls out numbers to back up his allegations. In the last nine years, the district attorney's office has only brought three brutality cases against San Jose police officers. All were charged as misdemeanors, and only one resulted in a conviction. But in half that time, the city has paid hundreds of thousands of dollars in cash settlements in 41 cases of alleged police brutality that the city attorney felt might be lost in court. This year alone, seven people have been shot and six killed by San Jose police officers, already more than the national annual average for a city this size. In the four cases in which the investigations have been completed, all of the officers have been exonerated. "Darryl is almost like a godsend," says Ronald Roland, a member of the Tribunal. "Before, no one wanted to do anything. Everyone was afraid to do anything. I am not religious, but the Lord had something to do with all this. Darryl is tenacious; he does not just give up." As the march rounds the corner on Second Street, turning toward its destination, St. James Park, Williams begins to relax a little. He is confident that his group has the right message. The key, he says, is presenting it in the best way. "We need to be professional enough to get our message across to corporate America," Williams says. The problem is, Williams' message is one that most Silicon Valley residents and upper-middle-class workers may have a hard time believing: that the well-trained and cordial police who maintain the city's relatively low-crime status and chat happily with customers at Starbucks also work alongside rogue officers who are racist, violent and out of control. If the Citizens Tribunal assessments are correct, the mostly good cops of San Jose routinely turn a blind eye to the inappropriate conduct of bad cops, allowing abuses to continue. For many people, it is an incongruous picture at best. But Williams is undeterred, not only because he says the facts line up on his side, but also because it is a message he had a hard time relating to just a few years ago himself. "I was cozily in my own life. I had an awesome salary, I was in charge of all of this, running the show. My wife was doing well in her profession, the kids are cool. It's going on, and all of a sudden--bam, just like that," Williams says, slapping his hands together and stopping, his entire life came to a standstill. Though Williams rarely talks about it, since 1996 his life has completely changed. This crusade to root out corruption in the criminal justice system is not just ideological. It is utterly personal.

THE NAACP OFFICE IN San Jose is little bigger than a kitchen, and the wispy breeze outside is no match for the heat, even with the door open. But Williams barely notices. His cell phone rings and rings until he finally turns it off. Phone messages also come to him through a line at the NAACP. As he talks, he rests his elbows on a daily planner that is fatter than a King James Bible, containing the details of the startup Citizens Tribunal and his life. An attorney has volunteered to file papers so the group can become a nonprofit, he explains. Some musicians are writing a theme song for the Tribunal and want to make a video. Attorneys and all kinds of people with special skills are contacting him, wanting to help out. And more people are coming forward all the time with new cases of police misconduct, bearing reams of court documents and police reports, which must be reviewed. Because he spent decades rising through the ranks of corporate America and is now marching in the streets, he is convinced that he can reach out to other office-bound middle Americans and bring them out of the cubicle and into the street. Williams moved to San Jose and played football for James Lick High School in 1971, where he quickly became a star running back. To this day he radiates the good-natured iron persistence that makes good running backs great: an unwavering faith that each time the ball is placed in his hands, something will open up, despite the odds he'll land face down in the mud. After graduation, Williams got married, began raising a family and started work in the radiology department at Alexian Brothers Hospital in east San Jose. Eight years was enough, he says, and one day he just left. As Williams explains it, he knew it was time to go, but he wasn't sure why, or where he was going. He just up and left. He enrolled in a machining program at Moffett Field and took night classes at San Jose City College. He spent the next two decades at three different machining companies, making parts for high-tech giants like AMD and Intel. He quickly rose to supervisor and then manager. His entire life, Williams says, the Lord has guided him. Though he belongs to no specific church, preferring to float from one to another, he was raised as a born-again Christian and passed that faith on to his family. And he firmly believes that the spirit of God has put him where he is today. For two decades, Williams' life was good. His marriage was solid, his family close. Then one day everything changed. Police arrested one of his sons for participating in a crime no one in the family could believe. Elias Williams, the third of Williams' six children, graduated from Mount Pleasant High School in 1995. He is a quiet kid, Williams says, and rarely even went out at night with friends. He worked full time at Circuit City. He played football like his dad and planned to go to San Jose City College in the fall of 1996. But on Feb. 8 of that year, his father took him to the San Jose Police Department to talk with an officer about a disturbance at a local high school. By the end of the day Elias was in jail, charged with attempted murder. Williams was at a complete loss to understand. He was the kind of parent who stayed up late waiting for his kids to come home. He knew their friends and says he often had long talks with Elias. Williams says he knew his son very well and he was no gang-banger. Williams used up all of his vacation time sitting through the trial day after day, trying to piece together what had gone wrong. According to police officers who testified about the night the crime was committed, Williams' son Elias, his nephew, James Broadway, and two other boys, Corey Holmes and Terrence Tyson, had been attending a talent show at Independence High School. In the parking lot afterward, they had a verbal spat with three guys who had also been at the talent show, Maurice Bagsby, Fred Gordon and Andre Smith. The officers say Williams' car drove down the street, away from the school, then turned around and came back. Police say someone in the car yelled "MPH," for Mount Pleasant Hoods, a local street gang, out of the car window. Then someone fired gunshots from the car. Smith, a member of a rival gang, was hit in the leg in front of hundreds of students. Under the law, a street gang is defined as having at least three members; the prosecution argued that the four young men in Elias' car constituted a gang and that they had fired at a member of the Cartel Crips, a rival gang. The shooting was charged as a gang-related crime, which carries an additional sentence in California. Williams attended proceedings in shock. As far as he knew, his son was not the kind of person who was going out at night to do drive-by shootings. He was heading to college in six months. He had never even been arrested before this incident. Neither he nor his son knew Terrence Tyson or Corey Holmes well. Williams says that his son did drive out of the parking lot and past the school, as officers say. But his son was not out to shoot a rival gang member. He was merely driving his cousin home. No one fired a gun from the car, Williams says. Sitting through the testimony day after day, Williams got to know some of the other parents of the young men being charged in the shooting. Most of them stayed all day. But there was one, Sharon Tyson, who often left early. Williams began to talk to her outside the courtroom. Though she wouldn't say where she was going in the middle of the trial, one day she told him, "Mr. Williams, if it was not for Terrence [Tyson], your son and nephew would not be here. I can't tell you more than that, but it is what I believe." Williams didn't know what to make of it.

Truth or Darryl: Citizens Tribunal leader Darryl Williams has created personal contacts and made inroads into improving the local criminal justice system despite the failures of others before him.

AS THE TRIAL PROCEEDED, Williams began to get suspicious that something was amiss. The testimony of the victim and his friends was often contradictory. One of the witnesses, in fact, was unable to identify Elias' car in a photograph, but knew the make and model by name. Halfway through the trial, the victim, Andre Smith, changed his story about where he was standing when he was shot. Initially, he said he was at a Wendy's a quarter of a mile away from the school. Later, he said he was shot right outside the school, an account which fit better with the evidence. Officers found a .38 caliber shell on the street near the school's gate. Police investigators said they also found a .38 caliber shell on the floor of Elias' car, although it was searched weeks after the shooting. But there was no gun. Meanwhile, the bullet that hit the victim, Smith, remained lodged in his leg--and no one knew for certain what kind of bullet he had been shot with. One ballistics expert even testified that a .38 caliber bullet would have shattered the bone, rather than lodging in it. Though police officers said that the shooting took place in front of hundreds of people, there was no testimony from neutral bystanders. And according to related court papers, officers did not even interview any of the hundreds of potential witnesses in the parking lot. "I was sitting in there and nothing added up," Williams says. Despite these holes, police officers were able to paint a picture of violent, unruly gang members who had finally been brought to justice. Without any reason to question the officers' testimony, the jury bought it, says Kat Kozik, Williams' appellate attorney. Williams' son and his nephew were each sentenced to 15 years to life for attempted murder. But the same sentence was not handed down to all four boys. The jury believed testimony from Elias' brother that Holmes had been in a different car that night, and he was acquitted. Terrance Tyson, Williams later learned, had walked free. His family had suddenly come into a lot of money, which they used to hire a new attorney, Harry Gruber. Williams found out something else: The money had come from the city of San Jose, which had paid $250,000 to the Tyson family to settle a 5-year-old police brutality and harassment lawsuit. Sharon Tyson left the courtroom every afternoon to attend those proceedings. Sharon Tyson says the charges brought against her son and Darryl Williams' son stemmed from officers trying to put pressure on her to settle her suit. She contends it was part of a long-standing harassment of her family after it witnessed San Jose police officers beating her husband, Lawrence Tyson, in his own living room in San Jose. "Whenever anything happened in the neighborhood, they would come to the house. Whenever anything happened, they would try to charge my son because they knew he was a witness [to the beating of my husband]," Sharon Tyson says. Ultimately, she admits, their strategy worked. As the family's suit headed toward trial, they realized that with Terrance's attempted murder charge pending in another courtroom, his testimony could easily be challenged, Tyson says. So Terrance's name was removed as a plaintiff in the suit. There would be one less witness, and one less child structured into the settlement. "I don't think Darryl's son was guilty," Sharon Tyson says now without hesitation. "The case should have been thrown out in trial. I sat in there every single day. It was such a horror." After accepting a $250,000 settlement from the city (one of the largest settlements the city has ever made in a police misconduct case), Tyson's new lawyer filed a motion for a new trial, based on the lawsuit and the close relationship between the officers who testified in the attempted murder trial and the officers involved in the brutality lawsuit. Judge Thomas Hansen agreed that the brutality lawsuit should have been brought up in the trial. Unfortunately, Judge Hansen had already thrown out Williams' son's and nephew's motions for a new trial and sentenced the pair to life in prison. Tyson was granted a new trial, and the county decided not to refile the case against him. Williams watched all of these machinations in dismay. He also learned about another piece of the story, after the fact. Smith, the victim supposedly hit in the drive-by shooting from Elias' car, had been facing felony rape charges, all of which were dropped shortly after his testimony. Meanwhile, Elias Williams was shipped to San Quentin to begin life in the California prison system. "Something like this just wreaks havoc on your family," Williams says. "It scatters you; it fragments everything." Williams believes his son was caught in the crossfire between the city, trying to defend itself in a losing case of officer misconduct, and the Tysons, who were just attempting to gain some restitution for the violation of their civil rights. But still, Williams has had to work hard to understand why the Tysons left him and his family exposed like that. "My wife and I, we wrestle with that so much. I understand why, but I know if we had known about the suit, none of this would have happened like this. That is the question that burns the deepest," Williams says, turning his head upward as he talks. "At the same time, my son was falsely used, used for a purpose, used to make three or more [people] as a gang. It was a wrestling match. Even now you bringing it up, it just really is something I think about. It was deep." After the trial, Williams went back to his job at Advanced Machine Programming and mulled over what he had seen in the courtroom. It bothered him, and he began to look for a way to change a system that he believed had failed to produce a just result. He began attending meetings of the county-appointed Human Rights Commission and volunteering with the NAACP. Then he started working with the newly formed Citizens Tribunal. He is appealing his son's conviction and recently won an important evidentiary hearing, the first step in reopening the case. Last fall, he quit his job and gave up his income to devote himself full time to publicizing cases that point to the systemic corruption that he believes reared its head in the courtroom. He wants to cleanse the system.

OVER PIE AND ICED TEA in the Marie Callender's restaurant off of Highway 101 in Morgan Hill, five members of the Citizens Tribunal and an attorney meet. Though everyone else is dressed casually--jeans, sweatshirts, sneakers--Williams wears a tie and slacks. He exudes the kind of professionalism that most people don't associate with a valley where millionaires wear khaki and activists wear whatever they please. Williams runs through the agenda while he picks at a salad. They briefly discuss racist traffic stops, profiling and other race-related police issues. But the agenda doesn't really get them too far. Today they pass around the press release for Ronald Roland's lawsuit against the city of San Jose. Like the Tysons, Roland is alleging a long history of harassment by the police. After Roland's son and friends were targeted as gang members, Roland, a 30-year San Jose resident, became outspoken about what he saw as an arbitrary racist policy designed to boost the city's gang numbers and flood jails with young black and Latino men. Soon, he says, his son and family became the targets of the San Jose Police Department. They were detained, arrested on charges that fell through. They even received an unsigned letter on district attorney's office letterhead saying that the witness intimidation charges brought against his son had been trumped up. Roland has had to move his family out of the area to protect them from what he calls continuing police retaliation. Gary Wood, a longtime activist and member of the Tribunal, pulls out his little black box containing hundreds of 3-by-5-inch file cards. Each one details a shooting, a beating, an unpleasant encounter with a police officer. He can't help but lay out the records of some of the officers involved in Roland's case. Williams looks on, nodding as Wood details one officer after another, some tied to San Jose's gang task force. It's a pattern that Wood has spent years following. But the group holds out a lot of hope for San Jose's new police chief, Bill Lansdowne. A longtime San Jose officer, Lansdowne left this city to become chief of police in Richmond, a much smaller city that also had problems with its police department. Many members of the Richmond community were sorry to see Lansdowne go. And even the cop-watchers around Williams were happy to see Lansdowne return to San Jose. They all are still waiting to see how effective he is in promoting change in the department, but, they say, at least Lansdowne is listening. "We were lucky to get him," Wood says.

Pride and Protest: A recent protest march in San Jose drew a crowd which included friends and relatives of people killed by police. The march was uneventful and many San Jose police watched from the sidelines. Darryl Williams later congratulated the force for doing a good job that day. IN HIS GLASSED-IN CORNER office, overlooking the parking lot of the San Jose Police Department's main office on Mission Street, Chief of Police Bill Lansdowne calls Williams a friend. Leaning back in his chair, gesturing with his hands like a presidential candidate, Lansdowne has only great things to say about Williams. "Darryl has a passion for what he does. He is very sincere and I think it is fair for both of us to say we are personal friends. We don't always agree on issues, or how we get to a certain position, but we have always been able to sit down openly and honestly and discuss the controversies," he says, pausing. "I think some good things have come out of it." Lansdowne defends his department and his officers but agrees that Williams has pointed out some problems the department has with the city's minority population. And the department is working to improve. He says officers have recently begun keeping records of traffic stops to try to address allegations that police officers pull over minorities more often than whites. Some police cars are now equipped with video cameras. The community policing program is growing. More officers are enrolling in the Critical Instances Training program that helps cops to handle mentally ill people in crisis or others who are stressed and armed and often unpredictable. These situations too frequently end with officers firing their weapons and leave community members asking questions. Despite these efforts, this year officers in the San Jose Police Department have shot seven people, killing six. That number is higher than the annual average for the last 10 years, and it is only August. According to statistics compiled by the San Francisco Examiner, San Jose has far more officer-involved shootings for every 100 people murdered than any other major city in California, including Los Angeles and Oakland. Lansdowne is concerned about the shootings but defends the record of his department. "We have taken a real hard look at it [officer-involved shootings] and it causes us to have concern to have so many early in the year. But we don't control the numbers of life-threatening situations we go to." Lansdowne points out that the average number of shootings over the last 10 years was six a year, not that out of line with what the numbers are now. And, he says, there is nothing to say there will be any more shootings this year. Lansdowne says he is surprised to hear about Williams' personal saga. "Darryl has never ever mentioned his son. That is totally new to me and I think that speaks to the professional relationship we have. He really feels he has a responsibility to others in this community to help and assist them," Lansdowne says. Though he admits he is not very familiar with the Tyson case, the allegations of long-term police harassment strike him as implausible. "In my experience, here and in other police departments, I have never seen a conspiracy that has been formulated in any manner or format to try to harass someone into dropping a suit," he says. Despite the allegations that Williams makes about some of his officers, and the ugly underbelly of the criminal justice system that he is prodding into the daylight, Lansdowne feels that his good relationship with Williams is important. And, unprompted, he offers another anecdote about Williams' good deeds. "Here is the mark of Darryl Williams which I appreciate very much," Lansdowne says. "He called me after that [march] and said, 'Hey, the officers did a good job.' He took the time to congratulate them for what he saw was a very difficult confrontation for them. That is a class act. It is tough to find a lot of fault with Darryl Williams when he is willing to give credit where credit is due."

AS THE TRIBUNAL meeting in Morgan Hill winds down, broad-reaching interests overshadow the group's focus on the police department. Williams brings up racism in the Alum Rock school district and tensions in the San Jose Fire Department, which recently went through a divisive lawsuit alleging racist promotional practices. He's following complicated complaints in family court. His sense for discrimination and injustice is expansive, and people are coming out of every tract and office park of the valley to tell their long-ignored stories. He reels in complaints from every corner, except his own. Conspicuously missing from his agenda is any mention of his son's predicament, of his own family's pain. That, he says, is not the purpose of his work. He is clear that his goal is to help others. His own family's suffering, he says, was the Lord's way of pushing him to act. It was an Old Testamentstyle wake-up call from above. And through the trial and incarceration of his son, the Lord taught him how to be effective. As one who understands what it is like to feel violated by the system, to be disbelieved, to be dealt a broken heart, he is perfect for the job. "I realize that if I had not experienced what we went through as a family, I could not see what I see today," Williams says, taking a breath. "And I could not see it in a way that makes me effective for other people." Williams visits his son in prison regularly. They talk about the trials and tribulations of their daily lives, similar to the talks they used to have, only now there is a difference: his son cannot act on much of his father's advice. He can only watch from behind bars as his father tries to pursue a personal vision of justice in his community, holding to his faith, refusing to give up. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the September 9-15, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.