Synch Different

If anyone can help synchronized swimming evolve from circus act to athletic event, it's male contender Bill May. But the officials at the Pan American Games and the Olympics are going to have to let him in the pool first.

By Gina Arnold

'THAT SPLIT-ROCKET was not a thing of beauty."

The remark echoes all over the north end of the Santa Clara Swim Center, and even those who have no idea what it means cringe when they hear it. It is being uttered through a microphone that is attached to the head of synchronized swimming coach Chris Carver, making her look as if she's an air-traffic controller--or possibly Madonna at Shoreline Amphitheater doing her soundcheck.

A soundcheck that is not going all that well, to be exact.

Carver is standing in the covered stands, staring down at nine synchronized swimmers. They are floating abjectly in the diving well, waiting to be commanded into various intricate shapes and formations. She is in the midst of inventing new routines for the Santa Clara Aquamaids' yearly synchronized swimming extravaganza, set to take place in this arena Sept. 11-13.

Carver is a pleasant-looking woman dressed casually in shorts and T-shirt, but her position in this organization seems to be one of complete authority and domination.

"Who," she says threateningly, "is not understanding that they're supposed to surface on one?"

After this question, barked abruptly into the microphone, it becomes apparent that humans have the ability to look shamefaced even when their faces are covered with white zinc oxide. The nine swimmers slink back to their start position. The music begins again, and they submerge, only to resurface in formation on--yes!--the count of one.

This has been going on since 7am, and it is a typical synchronized swimming practice for the "A" team of the Santa Clara Aquamaids--a group of swimmers who placed first in the last synchronized swimming championships. Along with three other girls from other teams, eight of these nine swimmers make up the U.S. National Team--and the one leftover, Anna Koslova, is ranked No. 1 in the U.S. She just can't compete on the National team until her citizenship papers are in order--set to take place in 1999.

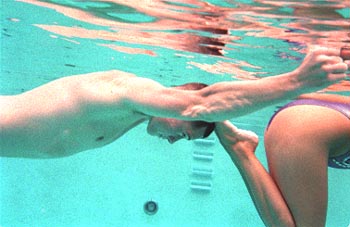

Yet another swimmer in this group also can't compete internationally because of an accidental feature of his birth. This one, however, is a boy--but you wouldn't know it to see him among his teammates. With bathing caps covering their hair, white zinc oxide covering their faces, and their straps off their shoulders (to prevent ugly tan lines), everyone in the pool looks pretty much alike. One can detect the gender difference only when the group treads with their entire torsos out of the water--an agonizing activity which they do all too often.

Indeed, many parts of the practice look agonizing--though other parts just seem chaotic or boring. "A work in progress" is what Carver calls it, but today the progress is tedious. At several points, the line of swimmers upends itself, lifting a row of eight beautifully sculpted legs vertically out of the water. Again, the fact that one of the legs belongs to a member of the male gender is completely undetectable. His leg--whichever one it is--resembles all the others, complete with curvy, muscular calf and perfectly pointed toe.

Carver continues to count--"Go-four-five, down-two three, four five six seven eight"--while beating in time on the metal railing. The bodies in the water twist and bend, attempting over and over again to achieve precision and synchronicity--an odd and almost hopeless pursuit. It is akin to the compulsory figures portion of ice skating, another exercise wherein human beings attempt to make geometric shapes with their body parts--only this one adds in the problematic element of mirroring other humans who are trying to do the same thing.

Needless to say, it takes an incredible amount of work--which may be why synchronized movement has been wrenched from the military arena and adopted by certain sports. Synchronized swimming has taken its share of ribbing since the event's addition to the Olympics in 1984--and it will take a fair share more, if Santa Clara's Bill May gets his way. But there's no way you can watch it being practiced by its champions without acquiring a healthy respect, and even awe, for the physical enormity of what they're doing.

Frankly, something about synchronicity seems to appeal to the human spirit. Think of giant armies marching into Red Square, the Blue Angels or the Jackson Five: can you deny that the sight of all these things strikes a joyous chord in even the most cynical breast?

After all, synchronization is an attempt to obtain order from disorder, and when it works right--as when one sees a perfectly synched flag team on a football field--the image is nothing less than majestic.

Aqua Moment: Though pairing with Bill May will prevent his partner, Kristina Lum, from competing in the Olympic duet event in 2000, the novelty of performing with a man in the predominantly female field compensates for the loss. 'I look at it like I'm just starting something new,' Lum says.

EARLY IN THE MORNING, when most of us are still abed, the athletes of the world unite. They rise before dawn to run, or swim, or bicycle, or skate, exhausting themselves in their pursuit. Each of them has a personal idea of glory: to win a gold medal in the Olympics.

But it's one thing when the dream is legible--like breaking a record in the 100 meters, a feat that will translate into thousands of endorsement dollars. But to become a perfectly synchronized swimmer? Such a goal is unintelligible to most people. Indeed, synchronized swimming may well be the sport that treads furthest from the Olympic creed of citius, altius, fortius (swifter, higher, stronger). In ancient Greece, to run faster or wrestle better were goals that had practical, and even financial, applications within the military society from which all athletes were drawn. To wear a bathing suit and dance in group formation does not.

It would be a mistake, however, to believe that because synchronized swimming has no natural place in war, it is not extremely difficult to do. In competition, the sport consists of three disciplines--solo, duet and team--and in all events the competitors perform two routines, a technical one and a free one. (In some competitions, they also do a set of compulsory, stationary figures that test basic skills.) The sport is judged on style, difficulty and synchronization, the latter being the exactness with which one athlete can mimic another's movements.

But there is another odd component apparent in synchro-swimming as well: the ability to make something that is enormously tiring--namely, performing in the unstable medium of water while incurring an enormous oxygen debt--look effortless. Thus, the Greek ideal it most resembles is not the Olympic one, but the one known as "stoicism."

In the works of Plutarch, stoicism is represented by the story of the Spartan boy who steals a fox and lets it eat his guts out under his cloak rather than admit to being a thief. Now, if the boy had put lipstick on and smiled throughout his interrogation, he'd be a prime candidate for the U.S. synchronized swimming team.

To date, however, only one boy in America has actually achieved that Spartan level of attainment. His name is Bill May and he is a 19-year-old member of the Santa Clara Aquamaids--and if the incongruity of his club's name and his gender strikes you as worthy of some ironic comment, you can rest assured it's a comment Bill has heard before. He's heard it all, from comments about Martin Short's synchronized swimming skit on Saturday Night Live to the more positive spin about getting to hang out with all those girls. The remarks just run off him like water off a duck's back (or, to use a more synchronized swimming-type simile, like water off a face covered in zinc oxide).

Happily, May is one of those super-single-minded athletes who lives in a dense fog of determination. His world is a small one, made up of a lot of people who take synchronized swimming very seriously. From early on in life he's known what he wants to do and just how he's going to have to do it, and no one has managed to deter him yet. This spring, he and duet partner Kristina Lum won the U.S. synchronized swimming championships and went on to take the silver medal in the event at the Goodwill Games. Although their team is banned from the Olympics (which designates the event May competes in as "Women's Synchronized Swimming" only) and was recently rejected from participation in the Pan American Games, May is allowed to compete in non-FINA (Federation Internationale de Natacion Amateur) events like the Swiss Open and the U.S. Nationals.

If May has his way, he will become the first male athlete to integrate an entirely female sport, a kind of affirmative action flip that incurs certain reservations in the breasts of feminists the world over. After all, desegregating one of the many male-dominated sports makes sense, but desegregating a female-dominated sport just seems like horning in. What's the point?

The point, says Aquamaids and U.S. Olympic coach Chris Carver, is merely one of logic. "I train athletes," she says, "not males or females. The political aspects of this thing are not my concern."

Besides, she adds, there's no real reason why men shouldn't synchronize swim--and indeed, when the sport began, they did. "I think it's an accident that more don't now. It's kind of like, not that many boys play violin. America is a society that likes contact sports. It's not supportive of artistic pursuits. In places like Russia and France, where male ballet dancers and gymnasts are more accepted, so is synchronized swimming."

But Carver didn't invent the idea of the mixed pair--the idea of a mixed pair presented itself to her when May arrived at Santa Clara. "I'd heard of him for years," she says, "you know--there's a boy in New York who's pretty good." It was only after May came to Santa Clara one summer for choreography and decided to relocate that she was presented with an opportunity to reshape the sport as a whole.

And even then it took a while. "When he first came here, he wasn't as good as he is now. I didn't think he could play the role he has now," she says. "He and his first partner did more traditional routines, hoedown, brother-and-sister kind of stuff. As he matured, he needed a partner with more strength and artistry."

The result was a pairing with national champion Kristina Lum--and the eventual invention of a duet routine that stretched the bounds of where synchronized swimming is going.

Carver had seen male-female duets in France, where synchronized swimmer Stephane Miermont, who later came to Santa Clara to coach, trained. Until recently, the Aquamaids also had another French male member, Benoit Beaufils. (Both these men are currently working with Cirque Du Soleil in Las Vegas.) But neither, she says, was as good as May is now.

"He has all the things I look for in an athlete. He's very flexible--he works at that every day, which many of my girls don't. He listens well, he follows instructions, he never misses practice."

The latter is a key point, since synchronized swimming demands total absorption. Carver herself--just returned from a three-week trip to South Africa, where she held synchro workshops in Durban and Capetown--has spent about 12 hours a day at the pool in preparation for the upcoming show, and her athletes also have no trouble reconciling the seven to eight hours a day of practice they are asked to incorporate into their lives--at the inevitable expense of things like education, career and home life.

There are rewards, however, to pioneering something. At the Goodwill Games last month, Carver was approached by a Chinese official, who invited her, Lum and May to China in October to demonstrate the idea of a mixed synchronized swimming pair in his country.

And that is a very substantial step indeed--because if China decides it wants to go in for mixed-pair synchronized swimming, then the event is guaranteed to develop at a rapid rate.

"They don't have the cultural roadblocks we do," Carver points out. "They'll just take all the little boys out of villages and make them do it--kind of like they do with diving."

"Cultural roadblock" is a nice way of saying "prejudice." In America, the idea of men doing synchronized swimming seems positively gay--but in fact, strictly speaking, it is the opposite of gay. The sight of May and Lum performing to Ravel's "Bolero" is, frankly, a lot more natural-looking than the sight of two women mirroring one another's movements.

Dive-versity: With the emergence of Bill May and other men in synchronized swimming, it seems likely the lip gloss and sequins will go away and the athleticism will become more prominent.

THIS MAY BE WHY May's current duet partner, Kristina Lum, says, "When we first heard there was going to be a boy on our team, we were all fighting to be partners with him."

Lum is sitting in the stands at Santa Clara this morning--sitting, as she has been for the last few weeks, because she incurred a back injury months ago when she was thrown out of a team lift into a hyperextended arch. Because this happened just before nationals, the world championships and, finally, the Goodwill Games, Lum's been living on cortisone shots and competing anyway, but now she's taking the time to let it heal. She is wearing a bikini top that shows off her pierced navel, and she seems pretty bored with the practice taking place in front of her, so she has plenty of time to tell me about 1996, the year that May moved to Santa Clara from his home in upstate New York in order to train full-time with the Aquamaids.

At the time, he was already an age-group champion, but the team he was on at the time only practiced three times a week. In order to move up in the rankings, he knew he'd have to increase his practice time. His parents--who sound like saints--let him go.

May's first partner at Santa Clara was Stacey Scott. When he improved enough to go from B team to A team, coach Carver paired him with Lum--a national solo champion whose partner had just retired from synchro in order to concentrate on school. Ask Lum if it's emotionally any different practicing with a man or woman, and you'll pretty much draw a blank: like many athletes, synchronettes seem to relate to one another as athletes and teammates, and not as males or females.

What's different, she says, is performing with May. "Normally when it's two females, they do the same things, but it's very separate," she says. "Whereas everything we do is very close together. We pretty much tried to stay connected the whole time, do a lot of lifts and things intertwined."

Swimming with Bill, she says, is also easier, because "we know what we wanted to show to people. Like, last year I did Swan Lake--and it was like, 'OK, you guys--we want it to look like a ballet.' This is more like ... displaying your emotions. It's more theatrical, and that's kind of easier in a way."

Lum and May do a routine that is patterned exactly after Jayne Torvill and Christopher Dean's Olympic-medal-winning ice dancing program of 1992. They wanted to give the judges something very familiar, because what they are doing is so different from what synchronized swimming has previously been about.

But in a way, what they are doing makes perfect sense. No wonder all three of them--May, Lum and Carver--believe that by so doing, they can change the sport of synchronized swimming for the better. "Right or wrong," Carver says, "I would favor it over the regular duet. It just seems more natural. You know, two synchronized women can be very beautiful--but there's something very technical about it. Adding a boy gives it more dimension."

Lum, too, prefers it to the other kind of duet--despite the fact that by competing with May she is losing her chance to compete in the duet competition at the 2000 Olympics. "I look at it like I'm just starting something new," she says. "I have this opportunity to do this, and at the same time I can have my cake and eat it too--I could still medal in team."

But though she is losing one chance at Olympic glory, by swimming with May, Lum is also gaining something few female synchronized swimmers have achieved: massive personal publicity. At last month's Goodwill Games, where the pair won silver, she and May were the subject of far more scrutiny than an ordinary synchro pair--and in sports, scrutiny tends to translate into dollars.

May, for one, was interviewed on the Today Show, CBS, CNN, NPR and TBS, prompting U.S. Synchro publicist Brian Eaton to dub the event "The GoodBill Games." He has also been featured in People magazine, Sports Illustrated, USA Today and Outside, among other places. (Today, KGO radio is hovering about the pool, getting ready to interview him yet again.)

Even my dance teacher's reaction to the idea was positively violent. "But you don't object to male ballet dancers," I exclaimed, appalled at her sexism.

She thought for a second. "I guess I just object to synchronization in general," she said, finally. "It reminds me of the Rockettes and Busby Berkeley--it's a whole style which I find offensive and degrading. I object to women doing it but I really object to men doing it because then it's like they're burlesquing women."

This aesthetic judgment, though prejudiced, cuts to the heart of the matter. What's funny about men doing synchronized swimming? The same thing that's funny about women doing it. Perhaps that's why, in 1996, the French Olympic team was banned from using a routine in which swimmers attempted to portray the suffering of the Jews during the Holocaust.

The swimmers meant well, no doubt. But synchro's frivolous reputation outside its own confines is already ingrained, possibly because it came to prominence at the Chicago, the New York and the San Francisco world's fairs (in 1934, 1939 and 1940, respectively). The last two events featured two lavish Billy Rose productions starring speed-swimming gold medalist Esther Williams, who later starred in many Hollywood musicals.

Even today, synchro shows can occasionally be seen in fancy nightclubs, where titillating women dressed like mermaids cavort in strange scenery. It is very at home in Las Vegas, where a permanent venue for Cirque Du Soleil has just been established, including a routine that features synchronized swimming and synchronized diving.

Despite its circus-like aspects, however, synchronized swimming--or "water ballet," as it's known at recreational programs throughout the land--has been an Olympic sport since 1984, reaching that status way ahead of such sports as women's soccer, softball and water polo (which has yet to be instituted). But that it is deemed a sport at all is often decried by onlookers who find some of its antecedents and conventions (namely lip gloss, sequins and hairpieces) unathletic in the extreme.

Even more detrimental to its image is the fact that, along with boxing and wrestling, synchro is a one-gender sport--and as is also the case with boxing and wrestling, there are no real physical reasons for this, only mental ones.

Boxing and wrestling are considered violent, and thus antithetical to femininity: indeed, some men seem to get a sexual thrill out of the sight of women fighting, which makes the current craze for it quite unappealing.

Similarly, synchro's emphasis on certain ultra-feminine traits can be jarring when performed by men. When a woman leaps out of the water with a giant grin on her face to the tune of "A Chorus Line," no one bats an eye. But the sight of a man with a similarly plastic grin on his mug exposes such a gesture for what it is: phony.

All the same, this isn't an argument against men synchro-swimming: it's an argument for it, because it is only by confronting such gender stereotypes head on that we can conquer them. If men get involved in synchro, it seems likely the lip gloss will go away and the athleticism will become more prominent.

Moreover, it's only when men become involved in a sport that sports start getting respect. As it is, synchro is not the most monied of sports, but some of its top athletes are able to earn pin money in various unusual ways. For example, a group of athletes from Santa Clara Aquamaids and the Walnut Creek Aquanuts were recently seen on TV in the pool at the Hard Rock Cafe Las Vegas, on the Billboard Music Awards show, surrounding Steven Tyler of Aerosmith, who swam through their split legs. (Not surprisingly, given the tone of this scene, May was not invited to participate in this shoot.) The swimmers were paid from $350 to $1000 each, a lowly amount given the budget for most Aerosmith videos.

Another set of U.S. synchro swimmers got paid for doing a series of Mervyns billboard ads ("Synchronize your summer"), and Comedy Central also did a series of shoots with some athletes from Southern California clubs. (Incidentally, athletes are allowed to accept money without jeopardizing their amateur standing because these gigs are not assigned to them via any athletic rankings.)

Less lucrative but more fun are the private engagements that champion synchro swimmers are sometimes hired for. Bill May was recently flown with some other Aquamaids to St. John, Virgin Islands, where they spent five days at a resort living large in exchange for one show in the hotel pool per night. Other troupes have done similar engagements in Hawaii and Puerto Rico.

But no one joins a sport just so that they can win a trip to the Bahamas--and compared, to, say, basketball or even soccer, synchro has no earning potential. (Like nursing and teaching, this is partly because it's a ladies' sport.) Most colleges have relegated it to an intramural or recreational sport, although the NCAA has just designated it an "emerging" sport.

Still, it remains to be seen whether Bill May can singlehandedly integrate the sport of synchronized swimming. No one else has, although there have been more than a few men over the years. The University of Iowa has traditionally always had a synchronized swimming club that utilizes men, and Brian Eaton says that last year U.S. Synchro registered 44 male athletes--most of them in Masters. (This figure is up from 2 two years ago--and still represents less than 1 percent of all registered U.S. Synchro athletes.)

Since the departure of Miermont and Beaufils, May is the Aquamaids' only male athlete--but Carver says that because of Bill's prominence, the team has received inquiries from several parents of little boys who will be starting up in the fall.

If they do, U.S. Synchro might begin to regain some of the ground it lost years ago, when it eliminated the men's division of its championship. According to Donn Squire, coach of the Cypress Club in Carmel Valley, until quite recently the U.S. synchronized swimming organization has actively discouraged men from competing. Squire calls the competitive synchro world "very political" and "very sexist"; he claims that he and his partner, Del Neel, have been snubbed over and over because "two gay men coaching in a women's sport is just not that politically popular with U.S. Synchro."

Snubbing has not, however, kept him down. Squire, who has been coaching synchro in the Monterey area since 1960, began his own career as a synchronized swimmer in the '50s. He grew up in northern Ohio and started synchronized swimming at a Red Cross Aquatic Camp--a place, he says now, where they taught "swimming, diving, water ballet, water safety skills, boating, everything." Water ballet was his favorite subject there: "It was so much less boring than swimming wall-to-wall."

After getting a taste of it, Squire pursued the subject, attending a competition in Detroit and later joining a club in Pennsylvania. Needless to say, Squire's family was not supportive of his efforts. "They thought it was pretty embarrassing," he recalls. "I had to be pretty determined to put with the total resistance I got from people--especially from my father."

Nevertheless, Squire persisted, attending the University of Iowa, which has one of the few integrated synchro clubs in the country. In 1955, Squire won the men's National AAU Synchronized Swimming Championship--an event which is no longer held under those auspices or under that title, though whether this is because there are simply too few competitors to bother with or because such an activity was discouraged by the powers that be is open to debate.

In 1960, Squire took part in a tour organized by the Oakland Athletic Club's Norma Olsen, which promoted synchronized swimming worldwide. "She had very influential contacts in the swimming world," recalls Squire, "and was able to persuade FINA to have a demonstration of synchro at the Olympics in Rome."

Squire took part in the demo, and, he says, "in retrospect, it was a very intimidating experience. There were all these stuffed shirts looking at something they thought was really frivolous."

According to Squire, Olsen's work was instrumental in legitimizing synchronized swimming in the sporting community, as well as internationalizing its appeal. Although it only held its first world championships in 1973, by 1984 synchro was accepted in the Olympic Games at Los Angeles. Two events were held: solo and duet. In 1996, the team event was added; in 2000, the solo event is being dropped.

Of course, none of these events featured men, who are disallowed from international competition, including at the Pan American Games. The problem seems to be in the wording of the competition, which is called "women's synchronized swimming."

Ironically, this controversy echoes one that took place over figure skating in 1902. That year, Madge Syers came in second at the U.S. figure skating championship, beating out many men for the honor. Soon after, women were declared ineligible for the competition; it wasn't until 1906 that they were allowed a "women's figure skating championship" of their own.

Almost 100 years later, synchro is undergoing a similar growing process, one that says as much about the changing roles and expectations of men and women as that previous battle did years ago.

For example, one reason women weren't supposed to figure skate was because modesty dictated that they wear cumbersome long skirts. We can now see the absurdity of such a stance, so why not apply a similar broadening of standards to May's activities?

Of course, the big question about the advent of male synchro swimmers is, where will they all come from? Even Squire can remember coaching just three boys in the last 20 years. One, at Fort Ord, did it because his sister did it, but his interest petered out. More recently, the Cypress Club had two 11-year-old male members. One of them quit because his family relocated; the other, Squire says regretfully, was "henpecked" out of it by "a bunch of mean, nasty girls."

"If there'd been someone like Bill around, even as recently as two years ago, we might have convinced him to stay," he says. "It's very disheartening, because if they'd only stuck it out, by now he could have been much better--a real contender."

Christopher Gardner

BUT NONE OF THIS ANSWERS the $64,000 question, which is, What would make a man wish to synchronize his swimming? And the truth is, there really is no answer. We all have our obsessions, and Bill May's just happens to be synchro. It has been ever since he began the sport nine years ago, in his hometown of Cicero, in upstate New York.

"What happened was, my sister Courtney wanted to try synchro at a public pool program one time," he says, after having finally received coach Carver's permission to get out of the pool and relax. Up close and personal, he is a cleancut young man with short, dark hair, curly eyelashes and the perfectly honed body of a diver, gymnast or other top athlete. He is dressed head to foot in much-coveted U.S. National team wear, and luckily for him he looks good in red, white and blue. He has told his tale to the collected media of the world--indeed, he's already told it once this morning to KGO radio--but he's perfectly willing to tell it again.

"I did competitive swimming there and the synchro class was right after it, so we couldn't go home until she was done. It was either try it with her or sit outside the pool and watch her, so my mom told me to try it, just to be in the water and be doing something."

A few other boys tried it too, May recalls, but they dropped out before the first week was up. Not him. Soon he was on a local team, and when that dispersed he joined another. His team practiced for an hour and half three times a week--but by the time he was 15, this was not enough to meet his goals. "I wanted," he says matter-of-factly, "to go as far as I could possibly go, and I wanted to be on a strong team, and really to grow and learn in synchro."

Santa Clara, he points out, was known for being one of the best clubs in the world, with the best coaches and the most pool time. When May was 16, his parents allowed him to move to California, where he lived with a family whose daughter was an Aquamaid. There, he attended Santa Clara High School and began practicing daily. "Now," he says, "we practice more in one day then I did in a week at home."

May started out on Santa Clara's C team, but before long he'd moved up to the B team, where he was partnered with Stacy Scott. Last year, he was moved up to the A team and paired with Kristina Lum.

"That's been a great opportunity for me," comments Bill, "because she's one of the best synchro swimmers in the world and she represented the U.S. in solo synchro at world championships. So it's really exciting for me, although I've had to work really hard to keep up. She's very graceful and artistic and that's harder for me to do. We really have to work on me a lot in that part."

Another hard thing about synchro, he adds almost as an afterthought, is what he calls "getting kicked in the something. ... Sometimes you come home and you just feel like you've totally been kicked around and booted so bad ... you get kicked many times a day. We have to be in really close, and especially on lifts we have to be so close our legs are actually in between each other's--and that can be pretty scary. The biggest pain is just running into people, or pulling a muscle from a split, or a quick split move."

Another thing that "kills"--to use May's vernacular--is sheer exhaustion. Synchro swimmers spend a lot of time underwater. People, May points out, have been known to black out in competition. A typical exercise is going underwater with weights around the ankles, rising up at top speed with one leg extended vertically, and then submerging--and doing this over and over again.

"There's nothing in synchro that any synchro swimmer can do perfectly all the time," May says. "So you're always trying to make it perfect, which almost never happens. You can get so you master things, but there's always the days that you're not perfect, so you just keep working."

Another problem with synchro is the cold. The Santa Clara team practices outdoors, and in the winter, at night, it can get darned chilly, even in a heated pool. Kristina Lum remembers making a brief attempt at quitting the sport when she was 9, solely because of the cold.

May had never worked outdoors until he moved here, but says he didn't really mind. "It was like everything else. It was a big adjustment, but I knew how much I wanted to be in synchro, so it was worth it."

Interestingly, May says he's never experienced any negativity regarding his proclivity for the sport. "Once when I was in high school, my name was in the paper and a bunch of people came up to me and congratulated me," he says. "And that was about it."

And by now of course, all chance of ridicule is over. May's move here, which occurred when he was a junior in high school, has paid off in no uncertain terms. The Goodwill Games proved that once and for all by making him a celebrity.

Nevertheless, May does have slight reservations about the publicity aspect of the whole thing.

"I think that's good for synchronized swimming, but it's not especially good for me," he says. "Sometimes it gets a little, like, awkward. When people ask me why I'm in synchro I don't understand why they're not asking the other athletes. It's always hard for me when people ask what it's like being a guy in synchro swimming, because I'm like 'I don't know.'

"I'm just in it because I love it," he adds. "I mean, why not ask my teammates what it's like being a girl in synchronized swimming? It's just a sport you chose to do because it appealed to you and you love doing it."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Photos by Christopher Gardner

Christopher Gardner Christopher Gardner

Christopher Gardner IN SHORT, with performances like the one at the Goodwill Games behind him, no one's going to go on record right now against Bill May--at least not in the synchro world. Outside that world, however, is another matter. There, reaction tends to range from people who hoot with laughter to those who merely think it odd or perverse.

IN SHORT, with performances like the one at the Goodwill Games behind him, no one's going to go on record right now against Bill May--at least not in the synchro world. Outside that world, however, is another matter. There, reaction tends to range from people who hoot with laughter to those who merely think it odd or perverse.

Head Over Heels: For Bill May, it's simple why he chose synchronized swimming. 'I'm just in it because I love it,' he says.

Head Over Heels: For Bill May, it's simple why he chose synchronized swimming. 'I'm just in it because I love it,' he says.

Global Carnival The Aquamaids present a synchronized swimming extravaganza Sept. 11-13. Esther Williams will appear. Call for ticket information. International Swim Center, 2625 Patricia Drive, Santa Clara (408/792-3279).

From the September 10-16, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)