![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Barbed Memories

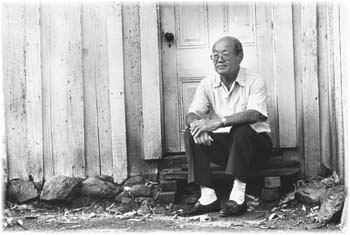

George Sakkestad One From Heart Mountain: Mamoru Inouye, guest curator of the new internment-camp exhibit, at his home in Los Gatos, A stash of previously unseen photos documenting the Heart Mountain internment camp gets a second life A POPULAR email circulating through the wired Japanese-American community recently came with the header "You might be Japanese-American if ..." The answers ranged from "You have an uncle named Ed, an aunt named Mitzi and a dog named Chibi" to "You have a lime-green patchwork quilt on your couch." Farther down the list was a more sobering reply: " 'Camp,' to you, doesn't mean hiking and cookouts." "Camp," a.k.a. the World War II internment camps, tested the mettle and patriotism of every Japanese-American on the West Coast. The uprooting of more than 100,000 people of Japanese descent, most of them American citizens, from their homes to the "relocation centers" was an embarrassing chapter in the history of a country that prides itself on freedom and democracy. While the predominantly Japanese-American 100th Battalion and 442nd Combat units were fighting the Nazis in Italy and liberating the Dachau concentration camp in Germany, 12-year-old Los Gatos resident Mamoru Inouye, his family and 109,994 other Japanese-Americans were cooped up behind chicken wire and guard towers at the Heart Mountain Relocation Center in Wyoming, one of nine internment camps spread out across the western United States. At the same time, two Life photographers, Hansel Mieth and her husband, Otto Hagel, of San Francisco, were assigned to document the daily goings-on at Heart Mountain. The bulk of the pictures never ran in the magazine, languishing in Mieth and Hagel's files for decades. A year and a half ago, Inouye, now a retired NASA aerospace engineer living in Los Gatos and a full-time Heart Mountain history buff, learned of the existence of the photographs and discovered that Mieth was alive and residing in Santa Rosa (Hagel passed away in 1973). Mamoru and his wife made plans to visit Mieth, budgeting an hour to flip through the photos. "They had lunch made for us," says Inouye, "so we spent the rest of the afternoon talking about her life. Then she showed me all these photos, and I saw a story unfolding." The stash of pictures so impressed Inouye that he decided to publish them himself in book form as The Heart Mountain Story. To mark the arrival of the book, the photographs are on exhibit at the de Saisset Museum in Santa Clara.

PHOTOGRAPHERS like Ansel Adams, who shot pictures at the Manzanar camp, captured the bleakness and loneliness of the barren landscape. Mieth and Hagel, on the other hand, struck a balance between photojournalism and sympathy for the internees. With the help of internee and journalist Bill Hosokawa (author of Nisei), the two photographers were given an inside tour of the Heart Mountain facilities. They spent just one day at the camp but were able to record a large number of intimate stories. The photos depict a typical day in the life of the camps, where between 250 and 300 Japanese-Americans were interned. In stark black-and-white prints, a mother and two children huddle near a coal stove, their only source of heat. Two fathers bottle-feed their sons. A child smiles as a doctor places his cold stethoscope on her chest. A recreation hall is crowded with men playing Go. Alice Hosokawa feeds her son, Michael, in a deserted mess hall. The photos in the Heart Mountain exhibit also illustrate how the internees kept boredom and anger from consuming their lives. A woman, frozen in time, works methodically on her ikebana arrangement. Men slow-dance with their dates as a band vamps behind them. The Akiya family, seven strong plus two guests, is seen framed in a cramped barrack enjoying the guitar playing of Ed Akiya. Saratoga resident Jimmie Akiya, pictured in the right-hand corner of the photo, was 18 at the time. He recalls the shot as a surreal reunion. "Hansel came in and took the picture," says Akiya. "I remember being really surprised to see Hansel there at the time, because we've known [her] since the 1930s." One of the most poignant shots is the Heart Mountain High School flag-raising ceremony. Three hundred Japanese-Americans, stripped of their inalienable rights, gather in the snow to salute an American flag. MAMORU INOUYE'S internment saga began in May of 1942. Inouye, then a Saratoga Grammar School student, and his parents and siblings were sent to Santa Anita Race Track, where they spent six months living in a converted horse stable before being shipped to Heart Mountain. "The feeling in our family was the government ordered us to go," says Inouye. "Being 12 years old, I had no say-so. It was just a duty to go." Inouye mentions that the main annoyance at Santa Anita was the lack of privacy. "They had communal bathrooms just like army latrines and showers, with no bathtubs. Going to Heart Mountain was an improvement, better than living at Santa Anita Race Track for six months." Fifty years later, the camps are a distant memory to some and a lasting source of bitterness and resentment for others. Heart Mountain's residents have since gathered at least six times for official reunions. The last one, held in Las Vegas, had more to do with forgetting than remembering camp. Inouye expresses disappointment at how little the camp reunions focus on educational matters. The Heart Mountain book and exhibit serve as ways to refocus these gatherings. "In Las Vegas, there were three activities: a bowling tournament, a golf tournament and a slot tournament," says Inouye. "The reunions are more social affairs. To me, it's a typical Japanese-American function, whether it's JACL [Japanese American Citizens League] or Buddhist church. There's a rich history to be told by these people. Many have photographs taken in those days. There's more that could be done to educate others as well as the children." Inouye also expresses disdain at those who adopt more militant methods of expressing their resentment of internment. "Some people present material in a way that's inflammatory. For example, if you go to Wyoming, there's some people who say, 'You did us wrong,' but it upsets the people who live there, because they weren't responsible. There's a time for healing. To accuse people of things is not the way to heal properly." Inouye feels strongest about revealing the lies that were propagated against Asian Americans. "We, as Japanese-Americans, believed the propaganda in the press," Inouye says. "All that was presented by the Justice Department and military were lies. [Supreme Court Chief Justice] Earl Warren even admitted that no acts of sabotage were committed by Japanese-Americans. They were twisting things around to fit their purpose. There was no military necessity." According to Inouye, "the evacuation was just a culmination of what had been going on for 40 years on the West Coast, beginning with alien land law and the Chinese exclusion act. Most Americans don't know about it unless they live on the West Coast or near where the camps are. I had co-workers at Ames who were born on the East Coast who didn't know about the camps." The importance of remembering is also stressed by Ken Iwagaki, who was interned at Heart Mountain at age 14. Iwagaki now serves as a docent for the Japanese-American Resource Center Museum in Japantown in San Jose. "It's a part of U.S. history that so little is known about," he says. "We have people who come to the museum every day who say, 'I didn't know that Japanese people were interned during the war.' " The Heart Mountain photos bring out "the truth of what happened and the tragedy it caused and how there was no necessity for it," Inouye says. "People suffered, and one doesn't want it to happen again. Such an event shouldn't happen again to anyone in this country. That's the lesson to be learned." Inouye doesn't want to forget Heart Mountain, but neither does he want to burn down the White House. Instead, the Heart Mountain book and exhibit constitute a visual legacy, a historical bookmark for future generations.

The Heart Mountain Story: Photographs by Hansel Mieth and Otto Hagel of the World War II Internment of Japanese-Americans runs Sept. 19-Mar. 15 at the de Saisset Museum, Santa Clara University. Tuesday-Sunday, 11am-4pm. Free. (408/554-4528) [ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.