![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

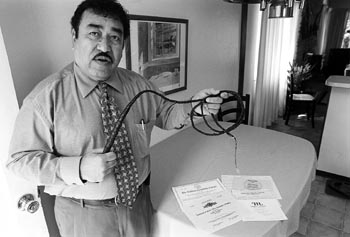

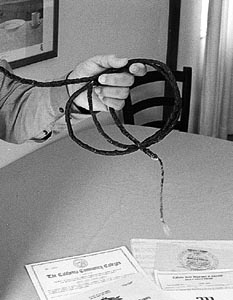

No Bull: Eugene Shands holds the whip one supervisor at NEC allegedly carried with her before a company investigation into charges of racism brought by Shands and others.

Corporate Punishment

In Silicon Valley, an enlightened working environment can include everything from free sodas to chair massages. Rarely does it include a good whippin', but that's just what one employee says his Rush Limbaugh-listening supervisor in the warehouse promised.

By Jim Rendon

EUGENE SHANDS REACHES INTO a folded manila envelope and lays a 7-foot black leather bullwhip across the couch in his west San Jose home. Shands says he's never used the whip, but keeps it as an unlikely reminder of his seven-year career with one of the county's top computer manufacturers--a reminder of everything that went wrong after he complained about years of racially motivated harassment and biased promotion practices.

Initially, Shands says, he loved his job at NEC electronics in Santa Clara. Shands, who is Latino and African American, started working there as a security supervisor in 1990 and thought it would be a great place to finish his career. He immersed himself in the work culture, serving as president of the recreation committee. He was a regular contributor to the company newsletter and had even been named employee of the month.

One of the few African American supervisors, he became role model and confidant to minority employees, many of whom worked in the nearby warehouse division. But starting in the early 1990s, they began coming to him with complaints of racism.

Epithets--all cited in a 1998 lawsuit against NEC by Shands and three other employees--included spic, nigger, sand nigger, ornamental, camel-jockey, cunt, whore and head-nigger-in-charge and were used in daily conversation. And one warehouse supervisor, several employees said, employed quite a unique management tool. She walked around the floor with a bullwhip in hand and occasionally waved it in meetings to emphasize her point.

Shands had heard that one warehouse supervisor was a Rush Limbaugh fan who sometimes broadcast the big man's radio show over the warehouse PA. When he finally met her, sure enough, he noticed the whip hanging on the wall in her office.

Shands is very light-skinned, so perhaps when he asked the supervisor about the whip, she was not aware that she was speaking to a man of African American descent. He says she confided, "This is for the colored boys; this is what they understand."

Office Perks

THE LAST THING Shands wanted to do, he says, was make waves at his dream job. He was 50, and with 20 years of experience under his belt he thought that if he played his cards right he had the potential to rise to upper management.

But then, Shands says, he started getting passed over for promotions, making the racial abuse that much harder to take. After years of receiving positive performance reviews without getting a promotion, Shands got frustrated. Many open supervisory positions were not posted and Shands believed they were being given to whites with less experience. When he applied for a promotion in April 1996, Shands had to fill out a 23-page document, something he said that no one else applying for a similar position had to do.

Finally, in February 1997, Shands met personally with NEC president Shigeki Matsue. Faced with Shands' description of the problems in the warehouse and security departments, Matsue offered to initiate an internal investigation. He promised Shands verbally and in numerous letters that "I will not tolerate any retaliation against you for bringing a complaint of this nature to my attention."

Matsue instructed Shands and others to meet with an outside consultant, Janie Jensen, of Workforce Dynamics, whom NEC hired to investigate the problem.

Initially, NEC seemed to be doing the right thing. Shands had identified four managers who were at the root of the hostile, racist environment he says was pervasive in the warehouse and security departments at NEC. Within months of initiating the investigation, they were all gone from the company. But the trouble for those who talked to Jensen was just beginning.

From Matsue's letters to Shands, it is obvious that he intended the investigation to be conducted confidentially. But Shands and other employees say that allies of the investigated supervisors seemed to know exactly who had complained. And as the fallout from the investigation began, Matsue's promise to guard them against retaliation fell by the wayside.

Ray Calloway, a warehouse employee who had filed official complaints against two supervisors in 1992, 1995 and 1996, says he found dog feces smeared on the inside of his company car. He says he also found the lug nuts loosened, and other employees close to the terminated managers threatened to "get him."

Shands found his authority in the security department constantly challenged by the new supervisor, human resources manager Bruce Calvin, who had been supportive during the investigation.

Though he was promoted, Shands says, his salary was far below that of the industry standard. And his authority was constantly undermined. He was given impossible assignments to complete and eventually was forced out on medical leave because the stressful situation was affecting his recovery from a heart attack he suffered during a performance review at NEC in 1996.

Calloway, like many of the others who participated in the investigation, worked under Calvin and soon found himself being pushed out of the company. Following a back injury, his supervisors refused to find a position that was more compatible with his medical needs. Like Shands and the others who participated in the investigation, he was placed on administrative leave for more than three months following the investigation.

Finally, in October 1997, Shands and a number of other employees who participated in the investigation filed official complaints with the federal Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Within two weeks of the commission's notifying NEC that complaints had been filed, both Shands and Calloway were fired.

'I AM VERY ANGRY," says Shands, who mortgaged his home and used up his savings in the year and a half it took him to find another job after leaving NEC. "I lost $30,000 a year including benefits and bonuses. There was a lot of stress."

In 1998, Shands and three other former NEC employees filed lawsuits against the company alleging race-based harassment and wrongful termination. Of the approximately 15 employees who talked with Jensen about discrimination at NEC, only a handful still work for the company, Shands says.

The four lawsuits filed by the office of San Jose attorney Richard Schramm were all dropped just days before NEC was required to respond, a decision Shands say he regrets. Schramm would not return calls to Metro about the cases. Now Shands and another plaintiff are filing new suits. Others are also looking into refiling their complaints. Former San Francisco Supervisor Angela Alioto is representing Shands.

"This is fundamental discrimination based on national origin," Alioto says. "These two gentlemen [Shands and Calloway] have been enduring this for years."

NEC spokesman Mark Pearce refused to comment on any of the specific allegations, citing fear of litigation, though at press time no lawsuits were pending against NEC for any of these allegations. Pearce did say that NEC is an equal-opportunity employer that treats its employees fairly and equally. He says that any claim of misconduct is investigated thoroughly as a matter of company policy. "We have a high level of respect for the individual and for decorum. We try to instill that in all our employees," he says.

And according to some former NEC employees, not every department had the kind of overt problems that Shands and Calloway experienced. "I got the feeling it was a good place for folks of color to work," says Dennis Mitchell, a former vice president of human resources who left NEC in 1996. Mitchell, who is African American, worked for NEC for 12 years before leaving. Though he left as a vice president, he says there are few minorities in upper-management positions at NEC or at other companies in the valley.

One current NEC employee who asked that her name not be used confirms that there were many problems in the warehouse department, but adds that they did not seem to bleed into other areas in the company. "I was really surprised about all this," she says, adding that things have improved since the investigation. "The company seems to be trying really hard to have a different attitude overall. Not just with what happened, but they are trying to bring up the level of professionalism."

But that happened too late for a number of people who feel that they were sacrificed unnecessarily after voicing their concerns. Shands, Calloway and the others feel burned by the way the company treated them.

"Retaliation is the one that I win with jurors," Alioto says, eager to get into the courtroom. "Retaliation is just as large as discrimination in the NEC case. Instead of learning the lesson, they compounded the problem. It never fails."

At home on break from his new security director job, Shands says he is also eager for his day in court. "If I can sit in front of a jury and tell my story," he says, "there is no way I can lose."

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![]()

Photograph by Larry Brazil

Celebrity Attorney

Celebrity Attorney

From the September 23-29, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.