Father Dearest

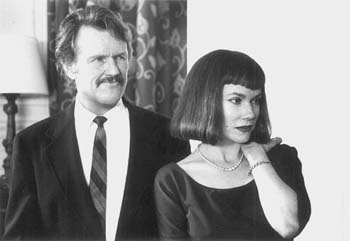

Not a Dry Eye in the House: Kris Kristofferson and Barbara Hershey star in the new James Jones memoir 'A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries.'

'Soldier's Daughter' walks thin red line in memoir about novelist James Jones

THE NOTED AUTHOR Bill Willis (Kris Kristofferson) lies ailing on his hospital bed. His daughter, Channe (Leelee Sobieski), starts to weep; with mock sternness, Willis reminds her that a soldier's daughter never cries. "But I'm a writer's daughter," she says, bursting into tears. And we all know how much writers' daughters cry; they cry all the way to the bank, directly after publishing a tell-all memoir. A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries is based on Kaylie Jones' novel about her father, James Jones, author of From Here to Eternity and other novels. Pleasantly, this film is the exception to the rule; if Ms. Jones is to be trusted, James Jones was everything a father ought to be: wise, responsible, brave, even-tempered, and open-minded.

The story is told in three parts. Part one involves Channe's life as the young daughter in a wealthy, indulgent expatriate household in Paris. She's made to welcome her new adopted brother, Benoît, later called Billy. In the second episode, it's the early 1970s. Channe befriends an effeminate, opera-singing school chum named Francis Fortescue (Anthony Roth Costanzo). In the third episode, she returns to New England for a rough adjustment to dull, conservative small-town life.

James Ivory directs listlessly--distractedly even. He drops major characters hard, unspooling this simple story into a film of unjustifiable length. The weakest segment is the second, following Channe's explorations of Paris in the company of Francis, an interesting companion but completely unsuitable for a boyfriend. Costanzo plays Francis as brash as New York itself, and with a near-castrato singing voice high-pitched enough to shatter glass. The film loses its way during a long Mozart recital by Francis; once again, we're reminded how poorly opera singers appear in close-up. This segment has one worthwhile comic tidbit, though. Francis, Channe and Francis' flamboyant mom (Jane Birkin) trip off to the opera to see Salome. The Strauss opera is staged disastrously in full Acid Age fig, with plastic inflatable furniture and prop hypodermic needles. It's costumed by some hopeless dropout of the school of Rudi Gernreich. That Channe is too tasteful to respond to the terrible staging is how we know she's too smart for the trends of the day.

Barbara Hershey, as Channe's mother, Marcella, is a hard-drinking, cigarette-smoking, scary old bird--like a sinful aunt you'd wish you'd had around growing up. Kristofferson gives a gruff, warmhearted performance that seems unrelated to anything realer than the movies. The most realistic of the family is Jesse Bradford, an actor to be watched. He plays the adopted son, Billy. Some of the only dramatic tension in the film comes from the skirmishing between Billy and Marcella, who nags her son about watching too much TV and for slouching on the couch. Billy's ordinariness seems far more real than the rest of the family's extraordinariness.

Sobieski was last seen as Elijah Wood's girlfriend in Deep Impact. She has poise and an unaffected, doll-like beauty, but she embodies the problems of the Merchant-Ivory movie: unnatural prettiness, dismaying cleanliness. But I didn't hate A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries. It's impossible to have a strong reaction to this kind of moviemaking. There isn't anything in it to offend or fascinate. Maybe it's enough that A Soldier's Daughter Never Cries portrays a childhood in a booze-loving, creative family as something desirable and fun.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Seth Rubin

A Soldier's Daughter (R; 124 min.), directed by James Ivory, written by Ivory and Ruth Prawer Jhabvala, photographed by Jean-Marc Fabre and starring Kris Kristofferson, Barbara Hershey and Leelee Sobieski.

From the September 24-30, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)