![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

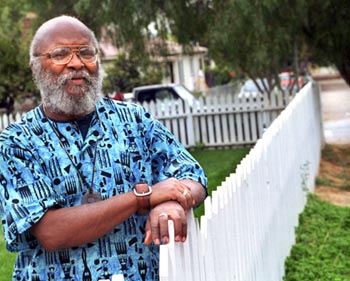

Photograph by George Sakkestad Highly Involved: Former East Palo Alto Councilman Omawale Satterwhite says the city has one of the highest levels of civic engagement in the state. Eastern Standard As "economic development" and gentrification move into East Palo Alto, Silicon Valley stands to lose its only black community By J. Douglas Allen-Taylor THERE IS A LOT of post-colonial smugness when white valley residents talk about the two-and-a-half-square-mile enclave that straddles Interstate Highway 101, tightly packed between upscale Palo Alto and Menlo Park. This is, of course, a low-income community that was hard-hit by the crack epidemic of the '80s, and in the early '90s became known as the murder capital of the country because of its highest-in-the-nation per capita homicide rate. Once an almost all-black community when it was chartered as a city 17 years ago, East Palo Alto is still a largely dark-skinned area: 53 percent Latino, 36 percent African American, 8 percent Asian and Pacific Islander. Only 12 percent of the population is white. The mayor is black. The chief of police is black. The superintendent of the local school system is black. Two of the five members of the school board are black, one is Latino, one is Pacific Islander, one is white. Four of the five members of the City Council are black. A black woman represents the area on the San Mateo County Board of Supervisors. Despite a dwindling population, black people still govern East Palo Alto. And in an America still consciously and unconsciously dominated by race awareness, the idea that it is a black-run city colors all thought and discussion about East Palo Alto. I reviewed recent coverage of the community in the Bay Area media and found that the stories were about either violence and/or corruption, the digital divide, or gentrification. Nowhere did I find any story that let responsible black East Palo Altans--and two of the persons interviewed for this story contend that media coverage is skewed against a black-run government like East Palo Alto--talk about their community on their own terms. White people sometimes screw up cities and governing boards all over the country, bankrupting the finances, throwing them into receivership, corrupting them with endless scandals. Yet no one suggests that this has any relevance as to whether or not white people ought to be allowed to govern. The City Council of the City of Berkeley is bogged down in internecine squabbles for years, paralyzing city government, and folks just roll their eyes and say, "Oh, that's just Berkeley." Chuck Quackenbush implodes as California Insurance Commissioner, but no aspersion is cast against all Republicans. And so long as they ply their trade in a white-majority setting, even black officeholders can stumble without darkening the qualifications of their whole race: Willie Brown has been dogged by allegations of kickbacks and double dealing during his years first as Speaker of the California House and now mayor of San Francisco, and all credit or blame goes to him entirely. But let the black superintendent of East Palo Alto's Ravenswood School District be accused of some misappropriation or other, and somehow, subtly, the whole notion of black governance in general gets called into question. Street Beat 'I LOVE THAT COMMUNITY," says San Jose teacher and resident Debra Watkins. The president of the Santa Clara County Black Educators Association has been a member of the East Palo Alto Seventh Day Adventist Church for 23 years. She raised a daughter in the church. "I've got so many friends over there," Watkins says. "I'm over there all the time, night and day. Even during the time when all those murders were going on, I never felt unsafe. I mean, the murders touched me. It touched everyone. The son of one of my good friends was killed. But personally, I never saw any of the violence." Watkins says she knows of many black valley residents who attend church in East Palo Alto, using it as a social and cultural base. "It's a beautiful community," she says. "A lot will be lost if most of the people who live there now are forced to leave. A lot of black homeowners are selling out. It makes a lot of sense. They can make a lot of money." She cites one friend who sold her home at a huge profit and bought another home at a lesser price in Modesto. "She made a lot of money. But her husband has a four-hour commute back and forth to San Jose every day. And she's miserable out there. She's lonely." Watkins is right about East Palo Alto. It is the loveliest of communities. I walk its neighborhoods under an August afternoon sun without the sense of danger or foreboding that newspaper articles have warned me about. But, then, I tend not to get nervous around a lot of African Americans, being African American myself. The backstreets are straight out of East Texas--they wander aimlessly with fits and starts as if laid out by someone who did not think residents had anywhere else to go but where they already were, devoid of sidewalks, shaded by every imaginable variety of tree. The houses are cool and low-slung, green-gardened and embroidered with religious icons of many faiths. Porch chimes tinkle in the hot summer wind. On a weedy, bay-bordering baseball diamond at the eastern lip of the city, a coach lobs slow balls at his young charges while other kids race bicycles along the levee above. Across University, another group of youngsters splashes the afternoon away in the municipal pool. It is a city seemingly made to order for children. Or almost. A young boy speeds by down the street on a motorized scooter. Within seconds, a police officer in a cruiser and another on a motorcycle give chase. I see them catch him far down the block, but never discover why. Under the gazebo next to the East Palo Alto Senior Citizen Center on busy University Avenue, a group of older black men sit on wooden benches, sipping beer and slapping dominoes on picnic tabletops. The African architecture of the gazebo, as well as the carved-wood king's stool and kinte-fabric chair-covering in the East Palo Alto Branch of the San Mateo County Library, hark back to a time when East Palo Alto was not only mostly black, but sought to both recast and rename itself in an African image. Bum Rap AS EARLY AS THE LATE 1960s, in a time when East Palo Alto was still unincorporated, young black community leaders sought to rename the area after the Kenyan capital of Nairobi as a symbol of the then-popular Black Pride and Black Power movements. "With a name like Nairobi," some activists told reporters from the New York Times, "everyone will know that we are black." In 1968, community residents turned the idea down 3-1 in a referendum, but several organizations and black leaders continued to press forward with the idea of a black-oriented city. A black business coalition was formed to help African Americans buy out white businesses who were fleeing the area. "It sounds like reverse discrimination," coalition leader Chuck Stevens told the Times, "but it is just something to protect ourselves." And Gertrude Wilkes, another black community leader, voiced the idea that East Palo Alto should be a black city. "We used to follow the whites," Wilkes was quoted as saying. "They would move out and we would go right after them. They moved and we moved. But we're not moving any more. We're going to stay here and make something of this place." And in early 1981, when petitioners filed papers to allow a vote on the incorporation of East Palo Alto as a city, they considered, but then rejected, putting the Nairobi city name to a vote at the same time. "We just thought that having the name on the ballot would give opponents one more chance of voting against incorporation," says longtime resident and leader Omawale Satterwhite. "We planned to return to that issue once the city was formed." Instead, Satterwhite says, city officials got so caught up in trying to govern East Palo Alto, and build its economic base once incorporation was certified in 1983, that the idea of renaming the city Nairobi was never revisited. Balding and white-bearded, the soft-spoken Satterwhite symbolizes the long history of East Palo Alto, from country township to incorporated black-dominated city to murder and drug haven to the coming economic upturn that will almost certainly end East Palo Alto as we know it. The Howard University and Stanford doctoral graduate came to the community in the 1960s, leading some of the black-oriented organizing efforts of that decade. He was elected to a term on the East Palo Alto City Council in the 1980s, and also served on the San Mateo County Planning Commission. In Satterwhite's view, East Palo Alto has received a bum rap from the media primarily because of its former black majority. "There is so much positive about this community," he says. "Pound for pound, this area has one of the highest levels of civic engagement in the state. People here have always been active." He cited the fact that once, in the 1980s, the community had 65 churches, almost all of them black, many of them participants in civic and cultural activities. In addition, he says, "the community has never had a serious ethnic conflict. In spite of differences, we've all been able to live together here." Even when the city has moved to clear up its problems, Satterwhite says, the media has not rushed to give it credit. In 1992, the year of the infamous "murder capital of the nation" designation, East Palo Alto had 42 homicides. Through August of this year, there were three. "The city showed tremendous leadership in getting the murder rate down," Satterwhite says, but calls media coverage of such successes "abominable." Today, Satterwhite sits in the meeting room of the ranch-style house that serves as the headquarters of the Community Development Institute, a training and consulting firm on leadership development that he founded in 1979. He bought the house and two lots in 1979 for $70,000. He now estimates its value at a half a million. Satterwhite's personal economic fortunes have taken a turn for the better with the rising economic tide, but he sees it as a bad omen for lower-income blacks in East Palo Alto. "This is an exciting time," Satterwhite says. "The economic development of East Palo Alto is what we lived for all these years. But in my wildest dreams, I could not possibly have imagined the clear and precise gentrification that is going on. We thought we could mitigate its effects and protect the black population better than we have. Now I can't imagine poor people being in the majority in this city in 10 years. The choices have probably already been made by economic powers outside this community. The plans have already been made. The land has been bought. Will poor people be primary in these plans? Naw, I don't think so. Capital has discovered this land."

Photograph by George Sakkestad

Taxed Out SAN MATEO COUNTY Supervisor Rose Jacobs Gibson says East Palo Alto caught the brunt of the drug activity in the 1980s, "but all of the consuming wasn't being done there," she says. "Lots of purchasers were coming in from Palo Alto and Menlo Park. In fact, there was more selling going on in East Palo Alto than actual using of the drugs. But, of course, because all the visible activity was happening in East Palo Alto--all the arrests--we were getting all the bad publicity." Gibson has an insider's point of view of the problem. She was voted onto the East Palo Alto City Council in the 1992 elections, the year of the murder capital designation and probably the low point in the city's history, a period that Gibson describes with one terse word: "devastating." Crime was the overwhelming problem for a city council that had only $200,000 in sales tax revenue to work with in its first years, barely enough to even finance its own council operations. "We didn't have a staff or an office," Gibson says with a small, sad smile. "For seven years, I was only paid $300 a month in stipends for city council work. I had to do consultant work on the side just to make a living, while doing a full-time job for the city. I was dealing with people who worked at Sun [Microsystems] or Silicon Graphics or IBM who just didn't have a concept of that. When they have a project at work, they have all of these resources to call on. But at the City of East Palo Alto, we mostly had to do it ourselves." By all accounts, they did well. The murder rate dropped 86 percent in 1993, and has stayed down ever since. "We decided that crime had to be approached from an area-wide perspective," Gibson explains. "It wasn't just an East Palo Alto issue. It went beyond our boundaries. The whole county was affected. So we brought in the Highway Patrol and the Sheriff's Department. And we got it under control. And that set the stage for the economic development that followed." The council next kick-started the Ravenswood 101 Project, which had been floundering. The area is now a successful retail development in view of the 101 offramp, with Good Guys and Office Depot as the anchoring tenants. But it came at a steep community price: the leveling of old Ravenswood High School, where many city residents had graduated from and then sent their own children. Across Highway 101, the council made another controversial economic development decision, tearing down a well-known collection of old businesses called Whiskey Gulch that included a cleaners, donut shop, barber shop, realtor, a hardware store, and a number of food and liquor stores. Now it is a vast, empty area along the freeway. Within a year or two, it will be reborn as University Circle, a hotel, retail and office space, and conference center complex that is expected to bump up the city's tax revenues significantly. Civic Duty GIBSON SAYS THAT East Palo Alto had no choice but to tear up some of its older civic and economic landmarks in order to build an economic base because it was squeezed in by larger surrounding cities, with no room for expansion in any direction. It is sadly reminiscent of the old Vietnam-era contradiction of U.S. military forces blowing up a village in order to save it from the communists. One hopes there is a point to it. "And, of course, Palo Alto and Menlo Park didn't make it any easier for us," Gibson says. "During the years just prior to [East Palo Alto's] incorporation, they annexed a lot of our open land for development, but at the same time they wouldn't bring our residential areas into the cities. It didn't leave us with a lot to work with." Now, she says, the city is faced with the delicate balance of trying to feed the fires of economic development while simultaneously keeping the heat from driving out residents who have waited so long to benefit. "The greatest gripes I hear are from those people who had hoped to purchase a home here, but now don't have the money either to purchase or to rent," Gibson says. "Some of us recognized a long time ago that unaffordability was going to be a problem, but most people didn't see it until it started getting out of hand. This wasn't a new issue. It's been brewing for a while. But it just surfaced in the public eye in the last couple of years. What we're seeing now is that even people with means can't afford to have their children live near them. The problem wasn't personally affecting them before. But when your children can't buy a home near you, then it's personal. A lot of residents are in situations now where their grandchildren live hours away. So for them, it's become a real crisis." Gibson says that East Palo Alto has traditionally been a stable, family-oriented community. She says she knows people in her mother's block who have lived in one home for 40 years, and says it is not unusual to find people who have rented apartments for more than a decade. "My goal is that everyone who lives here now ought to be able to stay, if they want to," says Gibson. "Where will the cooks, waiters be able to stay? Janitorial workers. Not to mention the teachers. These will all be needed in the new economy. We've got to make provisions for them. East Palo Alto can stay the way it is right now, with all of our diversity and family atmosphere, if it is the will of the community to maintain it. But people must choose to stay. The only way it will dramatically change is if we get a huge turnover, with new people coming in and completely replacing the ones who are here now. I hope that doesn't happen. I have a desire to keep what we have."

Home Court: Children amuse themselves at East Palo Alto's public recreation center. Class Struggle AT EAST PALO ALTO'S Shule Mandela Academy, they know all about tradition and trying to keep what they have. With some 100 children currently enrolled in a K-8 program chartered with the Ravenswood School District, the school sits on a spreading eastside lot that closely resembles the West African village East Palo Alto once strived to emulate. At the far end of the lot, a handsome bay horse stands near the fence and eyes the white-bloused children as they pass back and forth between the school and the lunchroom at the church next door, hoping that someone will pass him a treat. There is plenty to pick from in the school's garden. Ringed by cut bamboo pulled from a nearby stand, the garden sports fat, yellowing gourds beside rows of cornstalks, peppers, pea vines, spreading green collards, miniature tomatoes, red-bursting sunflowers, sweet strawberries, and green-orange pumpkins. While teachers shout instructions to their spirited charges, one young student walks across the yard to stop me as I lean over to sample one of the tomatoes. "Excuse me, excuse me," he says. "You can't go in the garden. It's not ready yet." After he is gone, I sample one of the miniature tomatoes to see if he was right. He isn't. It is sweeter than anything at Albertson's. I take a handful with me up to the schoolhouse complex, just to make sure. Dressed in an ankle-length, African print gown, Academy Director Nobantu Akoanda pushes the wisps of dreaded hair away from her forehead and tries to explain the difficulties of preserving an African American tradition in a community that is slowly being drained of its African American population. She's lived in East Palo Alto since 1974. "They say development is coming to raise the community up," Akoanda says. "But in fact, its intention is to move African Americans out. Other ethnicities are given variances and special allowances by the city. And if you're white, you can get anything you ask for." But isn't the city run by African Americans? Akoanda gives a dismissive gesture. "Yes. But they're just black faces painted on a white power. All this development is coming in, twisting and turning things around, making waves in the community, but it's not here to help African Americans. What was built in the 1960s and the 1970s is being totally destroyed. Gentrification and racism go hand in hand." Already, she says, several of the area's black churches have been feeling the population decline. Some are considering selling out to Latino congregations. She tells me to go take a look at the new housing development that is being put up behind the Ravenswood 101 center. It's an example, she says, of the designs to strip East Palo Alto of its soul and redevelop it as a sterile, suburban valley community. "In East Palo Alto, people have front lawns facing the street. They sit out on their porches, or work out there in their gardens, and you can talk to people as you walk by. But this new housing, you can see the way it's being built, it's unfriendly to the community. All the lawns are set in the back, away from the street. Everything is facing inward, as if they don't want to associate with the rest of us." Despite the fact that Shule Mandela has been in existence as a private institution for almost 20 years, Akoanda says it doesn't get the same recognition as other local charter and private schools. "We've got a track record," Akoanda says. "Over 100 of our students have graduated from college. But none of that means anything. We still can't get the same kind of financing and scholarships that other institutions can get. They say our governing body is not 'diverse enough.' Which means, of course, that we're too black. And so, we're not trusted with the money." A sad-faced, slender, young white man walks to the back porch of the school from the garden, offering strawberries that are sweeter even than my pilfered miniature tomatoes. After he has left, Akoanda explains that he is the school's gardener. "He's had a lot of trouble in East Palo Alto, being white," she says. "He rides his bike everyplace, and he's gotten threatened by some of the black kids around. One time, they pulled him off his bike. But like us, he says he's going to stick it out. He's determined to stay."

Schooling Society: At East Palo Alto's Schule Mandela Academy, director Nobantu Akoanda says the school can't get the same kinds of scholarships as many others because their governing body is not 'diverse enough.' Soul on Ice ALONG THE BAYSHORE freeway on the city's extreme eastern edge, I find the new development Akoanda has directed me to. It stands in various stages of construction, from bare, cleared ground to wood-frame skeletons to finished product. If this is East Palo Alto's future, it looks depressingly like Santa Clara County's high-tech present, and decidedly unlike East Palo Alto's historical friendliness. University Square is indeed soulless--a flat, treeless expanse of beige and beige-gray townhouses of three slightly different, interchangeable varieties, each house looking like the next, each street looking like the last, a tribute to an Internet-driven economy built upon interchangeable, seemingly indistinguishable chips. A couple of thirtysomething white women in shorts stand on the sidewalk with a clipboard between them, picking out something on a page. Across O'Connor Street, in the practice field behind the Boys and Girls Club, a hundred or so junior-high-age boys run drills to the instruction of barking coaches. While a handful of leggy young girls stands in the shade of a string of portable classrooms, pointing and picking out their favorite athletes, the lines of boys pound each other endlessly, back and forth, back and forth, up and down the field in that peculiar fall ritual called football. The sounds of the shouting and the laughing and the hitting pads wind across the near-empty street, almost, but not quite, overpowering the hum and the noise of the construction. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the September 28-October 4, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

The Place to Be: Many of the valley's African American residents attend church and other functions in East Palo Alto, using it as a social and cultural base.

The Place to Be: Many of the valley's African American residents attend church and other functions in East Palo Alto, using it as a social and cultural base.