![[Best of Silicon Valley 1999]](../gifs/bestbar.gif)

[ 'Best of' Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

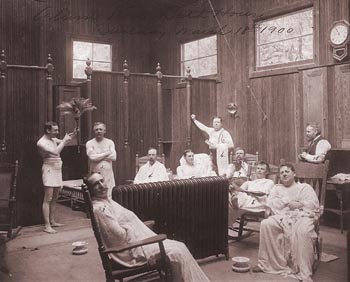

Wrap Group: The inside of the Alum Rock Bath House in its turn-of-the-century heyday, as photographed on Sunday, March 18, 1900. The handwritten numbers on towels correspond to names on the back of the print (courtesy of Bingham Gallery, SJ), which are as follows: 1. E. Michael; 2. J. Stevenson; 3. D. Hatman; 4. N. Metcalf; 5. T.J. McGeoghegan 6. E.C. Jobson; 7. H.L. Miller; 8. W.E. Henry; 9. Geo. Alexander; 10. H. Center. Best of the Millennium One thousand years in the Valley: A perspective By Corinne Asturias Long before orchards carved the valley floor into squares, before housing subdivisions sliced and diced them into even smaller parcels and before freeways crisscrossed the valley north and south, before silicon was invented, or before any European had even heard the word "America," the Santa Clara Valley was an entirely different kind of place than it is today. Imagine: where Willow Glen now sits was a lake; where the Tamien Light Rail station runs its tracks, an Indian village; where Highway 101 cuts its auto-choked swath, a wild stream. Just 250 years ago, the area we now call Silicon Valley was an Eden of creeks and ponds and artesian wells, supporting an ecosystem of animals including grizzly bears and herds of elk and plants like tules, wild grasses and spreading oaks. And almost anywhere in the valley, members of at least eight major California tribes of Native Americans were going about their lives hunting and fishing and collecting acorns, where many had lived for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. So in sizing up the millennium, we had to take all 1,000 years into account, not just the ones we've lived and are most familiar with. The task was tricky because for the first 750 years or so, there is no written record, only an oral tradition among people who spoke different languages (30 different ones, by some estimates), and whose populations and culture were decimated after the arrival of Europeans in 1777. Some of the categories were tough. Challenges to our choices are welcomed (email letters@metronews.com). Here are our selections for some of the almost-timeless things in the Santa Clara Valley, from the perspective of just one millennium, a thousand years. Purple Passion Apologies to Campbellites, but best fruit of the millennium is not going to the prune. Not the apricot, either. Despite the modern-day appeal of the valley's orchard period and the ample historical writing around it, this era occupied, in the context of the millennium, a smidgen of time. As did wheat, grown here before it. For this grand honor, we wanted a timeless fruit that has been here since the start. Plus it had to feed animals, be abundant and taste good. So we chose the native blackberry, a hardy bramble that can still be found near streams throughout the valley, and is a stubborn contender if introduced to an urban backyard. Blackberries once fed grizzly bears and giant herds of grazing animals. They still feed deer and birds and bugs. Humans can eat them too, if not by the basket, at least in the blackberry margaritas at Chevys. Dog-Eat-Dog World Early accounts of the valley and the study of modern-day biologists confirm that the valley in most of the past 1,000 years was teeming with wildlife, including bears, mountain lions, bobcats, deer, herds of elk and flocks of birds so big that their sudden ascent into the sky pounded like thunder. But again, a survivor was desired--an adaptable but untamable animal who had managed to hold onto its wild spirit and elude the encroachment of car-driving, tract-building humankind. Although their numbers are not what they used to be, we chose the humble coyote. They still wander along the ridges of the foothills, their haunting calls echoing at dusk through places like Sanborn and Alum Rock Park. They'll occasionally snare a cat from the backyards of mountain dwellers as well and offer a confrontational call of the wild to their kibble-fed cousins staring out from their Dogloos into the night. In Indian times, the coyote was considered a source of hidden wisdom, a creator and jokester, something which might be put to good use in the dog-eat-dog world of today. An amazingly adaptable animal, the coyote is a scrapper and a survivor. The rest of us, in time, can only hope to do so well. Room With a View Whether looking up into the heavens or down into the valley below, the views from the high point of Lick Observatory can't be beat on a clear day or night. Its overlook from the south end of the valley boasts views to the San Francisco Bay and beyond (some say they can see Mount Shasta). Lick Observatory was built in 1888 by the philanthropist James Lick, a Pennsylvania native who originally came to the valley to start a flour mill. In its early days, Lick Observatory and the spectacular 27-mile winding roadway leading up to it, was a huge tourist attraction heralded for offering the "most advanced astronomy appliances in the world." Scientists still man the observatory's updated, world-class telescopes around the clock. Drink Up Fresh water in the valley was once abundant. Indeed, for all but the last 200 years of this millennium, much of the place was like a swamp, with creeks and rivers functioning for the valley's early inhabitants the way freeways do today. Unfortunately, most of the valley's water sources are no longer suitable for drinking.(to make matters worse, the water coming out of the faucet looks like skim milk). For those wanting to remember how water is supposed to look and taste, drive north up Interstate 280, hang a left at Highway 92 heading toward Half Moon Bay and pay attention to the right-hand side of the road. Eventually you'll see a bunch of cars parked along a rocky wall and people waiting to fill up bottles. Stop and take a drink of the cool, clear water pouring out of the mountain, where people and animals have been partaking of it, for free, for several thousand years. H2O Zone An original creek much used by the Indians, as evidenced by artifacts in its vicinity, Coyote Creek (originally called an "arroyo") was crossed and noted by the early valley explorer Juan Bautista De Anza in 1776 and drawn on his now-famous maps of the area. Today the creek still runs some 25 miles from Morgan Hill to Alviso, where it spills into the bay. Much of it has remained unchanged, except for the fact that a highway runs alongside it and two lakes near Morgan Hill--Coyote and Anderson reservoirs--capture its waters as it loops northwest. Portions of the creek are still quite wild, originating in Henry Coe State Park. It serves as a recreational area for humans and a drinking-water source for wild animals, including its namesake, the coyote. Human Improvement on Nature No, not the building that looks like it's held up by a giant paper clip. For grand human visions we wanted something on the level of San Francisco's Sutro Baths, the successfully executed grand human notion to do something hugely wacky and unreasonable, but rooted in love and respect for a natural resource. The winner here, by historical accounts, is Alum Rock Park, originally called the City Reservation. One of the oldest parks in San Jose, Alum Rock in its heyday featured fountains of mineral springs where people could "take the waters" (sip them) for curative purposes or soak in them in gender-specific bathhouses. A train connected downtown San Jose hotels with the park for easy access. At one point the park added a huge swimming pool called the Natorium, which boasted a spring diving board, two high platforms and a long "death-defying" slide, all surrounded by spectator seats. Later they added a carousel and a small zoo, horseback riding and hiking. In the 1960s, the facilities were closed and the park switched over to being a natural trail park, home to bobcats and bobkittens, mountain lions, coyotes and even, on the back side, bald eagles. Pet Rock For years a huge black boulder known as the Alum Rock Meteor sat on the north bank of Penitencia Creek at the lower end of Alum Rock Park. Historians say it measured about 20 feet by 20 feet and had a sign nearby proclaiming it weighed 2,000 tons. As the story goes, everybody loved this pet rock from space and stopped their carriages to look at it. Even the train motormen would stop so passengers could get a better view. Some old-timers even swore they'd seen it land after a dramatic flash in the sky (scientists generally believed it had been there since long before the dawn of civilization). But one day reality came crashing down. A scientist from Lick Observatory said no, it was not a meteor. It was a huge chunk of manganese. As fate would have it, the country was embroiled in World War I and needed manganese for its war effort. So, being loyal Americans, the San Jose City Council voted to sell it to a mining guy for $22,000. Then more reality hit: it only weighed 389 tons. So the city didn't get its money, the mining guy went broke and the rock--and all the legends that went with it--turned to dust. Bloomin' Thing Best flower of the millennium goes to the intriguingly named Blue Dick, known in botanical circles as brodiaea. This native species, with its blue pompom of a flower, sits atop a long stalk, with few leaves at its base. It grows from a starchy bulb and was a major food source for the valley's early inhabitants, who would dig for it and mash it up. Today, the pretty purplish-blue flower can still be seen growing in the east foothills in spring, a cool contrast to the California poppy or bright yellow wild mustard. Not many who drive by it know its name, but those who do can point and say, "Oh, look at the blue dick." And a lot of people will turn their heads.

Tree of Life Early Spanish explorers who got here in the 1770s called this place "Llano de las Robles" (Plain of the Oaks) and one explorer, George Vancouver, even wrote in his notes that the valley looked like a manicured "English park" with oak trees spread across manicured grassy foothills. Take away the mansions and the view today is not all that different from a car window on I-280 heading north. All this beauty, plus a valley oak puts out 350 to 500 pounds of acorns per tree in a good year. Although no humans today eat acorns (we dare a creative valley chef to come up with a crispy acorn tortilla like the ones the Indians here fed to explorers), early inhabitants depended on them for about 800 years, collecting them by the ton, pounding them into flour and then laboriously leeching out the tannin with water. As late as 1877, scientists estimated that the California Indian diet still consisted of 56 percent acorns. In the 1940s, a guy named Carl B. Wolf actually did field trips with groups of researchers and figured out that a family of four Indians, with two kids, working eight hours a day for two weeks, could collect 17 tons of acorns. Monster Fish It's ancient, it's ugly and it's still swimming in the bay at sizes which are enormous by today's Bay Area fishing standards. The sturgeon has a face, well, only a mother sturgeon could love. A tough scavenger and a fighter, the sturgeon refuses to succumb to the pretty-boy standards of aquariums or even today's stock fish. For most of this millennium, the Indians snagged these monsters, smoked them, ate them and loved them. Reign of Rain The biggest and most dramatic recorded rainstorm and resulting flood in the valley occurred in 1861, although, according to historian Bill Wulf, few heard about it at the time. The closest records were kept in San Francisco, where meteorologists clocked 50 inches of rain in the winter of 1861-62, with 25 of them occurring in January alone. In the Santa Clara Valley, James Alexander Forbes and his sons had built a cabin above Los Gatos in hopes of finding quicksilver. The cabin was on high ground, but as the storms worsened, Forbes wanted to check on his family house in Santa Clara. In a letter to a friend in New York (which is preserved today), Forbes recounts trying to make the journey from Los Gatos to his home in Santa Clara by horseback, a journey he had done often before. This time, however, the valley was filled with water so deep, he wrote, that the horse was swept out from under him and he was forced to swim in waist- to chest-high water all the way to his home. The same season flooded most of North First Street and Agnews mental hospital. Bank Robbery From the vantage point of one of the valley overlooks, Dry Creek Road looks like a flourishing riparian corridor with humongous trees and lush vegetation. But where's the water? The answer lies in a decision apparently made by Los Gatos Creek 150 years ago to jump its banks and take a turn to the west. The creek's change in course was aided, according to some historians, by a couple of local farmers who dug a drainage trench at the back edge of their wheat fields. The creek, churning down through the foothills carrying runoff from the Santa Cruz Mountains, chose their trench instead of the course it had occupied for thousands of years. That's where it flows today, paralleling Highway 17 and the Los Gatos Creek Trail. In its original spot, the creek used to end in a two-mile by one-mile lake in modern-day Willow Glen--the reason, according to historian Bill Wulf, that "the sidewalks in some places are like roller coasters." Humans It was tough, and there were many contenders (not to mention thousands of people living here during the first 800 years who are not even recorded), but working with what we had, we chose Leland Stanford as best male human of the millennium. His work with the Southern Pacific Railroad helped connect the valley to the rest of California, and California to the rest of the United States. He was also the creator, in memory of his son, of Leland Stanford Jr. University, built as a free university, a place of opportunity for any person, regardless of finances, to gain a higher education. So much for good intentions. The university has served as an incubator for ideas that served to launch this valley into the next century and beyond. Stanford in his lifetime served as governor of the state and later as a senator. True, he was a robber baron, but a benevolent one. The combination of the transportation network he helped create and the university on the Peninsula made him a person of indisputable influence in bringing the valley from its rural past to its modern place in the next millennium. Female: One of the most detailed and compelling stories of life in this valley during the past millennium came from one of the area's last remaining full-blooded Indians, Ascenscion Solórsano. Ascenscion counted herself a member of the San Juan tribe and was a healer who lived in Gilroy until her death in the 1970s. She was well-known in the area, consulted by thousands for her knowledge of herbs and their curative powers. In the last days of her life, she told her stories and memories to Smithsonian ethnologist John Harrington, who carefully recorded them. Her account is rich in detail--she knew she was dying and saw Harrington as a person sent from God to record her words. She said the area now known as Silicon Valley was called Popeloutchom, and people living here believed it was a paradise. Her people, she said, traced their roots back hundreds of generations to tribes east of here. Their secret to longevity and good health was immersion in the waters of the valley each morning, regardless of season, regardless of age (even newborn infants). The men shot birds out of the sky, and deer with fast bows and arrows so sharp they sometimes traveled straight through the bodies of their quarry. The women collected acorns and were believed to have magical powers with plants. We have chosen Ascenscion because, better than anyone else's, her lucid memories served to preserve the valley's history and knowledge of this millennium for future generations. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the September 30-October 6, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

Tree Hugs: The Valley Oak took honors for best tree of the millennium for its character, longevity and presence at the dinner table of early inhabitants who depended on its acorns for food.

Tree Hugs: The Valley Oak took honors for best tree of the millennium for its character, longevity and presence at the dinner table of early inhabitants who depended on its acorns for food.