Dirty Rotten Scotsman

The author of 'Trainspotting' looks at Edinburgh's seamy side from the other side of the tracks

Review by Michelle Goldberg

AT EDINBURGH CASTLE, a combination pub and club in downtown San Francisco, the line to get in goes down the block. Inside, DJs spin hip-hop and jungle, lights flash, and crowds throng around the stage in anticipation of the main event. The heat is thick, and soon girls are peeling off sweaters and jackets to reveal tiny, strappy camisoles and tank tops. Pot smoke fills the air and pints of Guinness slosh and leave puddles on the floor.

Finally, after several opening acts, the star of the show appears to wild cheers. Is he a rock legend? A famous DJ? No. He's Irvine Welsh, a Scottish writer who's in town to read from his latest novel, the scathing black comedy Filth, and his reception is a sure rejoinder to anyone who claims that young people don't care about fiction anymore.

Welsh is best known as the author of Trainspotting, which, of course, later became the hit film that launched the career of Ewan McGregor. Welsh is also a writer heavily anointed with media clichés, often called "the voice of the chemical generation," because of the drug-drenched milieu of his work.

His past novels and story collections have all followed the junkies, hooligans, hipsters, ravers and lowlife criminals of Edinburgh's underclass. In Filth, he examines the other side, taking as a narrator a cop who spends his days tormenting those that Welsh usually writes about (characters from Trainspotting and Welsh's second novel, Marabou Stork Nightmares, even make cameos).

Filth, however, is Welsh's most antiestablishment book, because its protagonist, Detective Bruce Robertson, is more vile than all the thugs and drug addicts from his other novels combined. The Criminal Justice Act, a British law that cracked down on raves, the nomadic subculture called travelers and other aspects of British youth culture, created a national mood of profound hostility toward the police, and Filth is a manifestation of that rage.

Although house and techno culture doesn't play a big part in his fiction, Welsh is often identified as a rave writer. In a way he is, because he says it was house music that inspired him to start writing in the first place. "I went through three phases in life," Welsh says at an interview a couple of days after his reading.

"One was when I left school when I was about 23," he says, "which was basically just tossing around in dead-end jobs and getting fucked up on drugs. The next phase was sort of cleaning up, getting my career together and getting into this more yuppie kind of thing. House music led me out of that mess, and so my next phase was getting into house music and writing. I was really down on drugs for a while. I wanted to be straight, I wanted to be clean, I wanted to get a career. I'd gotten into all that '80s bullshit.

"I was into the music first and foremost. I still don't really think I am a kind of rave writer or a chemical-generation writer. It just seemed to me that there was no one writing about the way people actually live their lives. You read a book, and there's no mention of drugs in the book at all; to me that's just completely pretentious in this day and age. Because everybody takes drugs in some form. It was like, what kind of world do these people live in? It bore no resemblance to the world I lived in or had grown up in. I wanted to write the way I saw reality."

WELSH IS FAMOUS for his trademark Scottish patois, which can be hard for a reader to crack at first but, once deciphered, settles into an intoxicating rhythm. Take one of Bruce's rants in Filth, a self-deprecating poke at Welsh's own popularity: "A jakey mumbling fuckin crap poems at people who dinnae want tae fuckin well hear them. So that's what they call art now, is it? Or some fuckin schemie writing aboot aw the fucking drugs him n his wideo mates have taken. Of course, he's no fuckin well wi them now, he's livin in the south ay fuckin France or somewhere like that, connin aw these liberal fuckin poncy twats intae thinkin that ehs some kind ay fuckin artiste ... baws!"

While Welsh's writing isn't about rave, he credits house and DJ culture with inspiring his punchy, slangy aesthetic. In the past year, Welsh has himself become a DJ, spinning all over Britain, the U.S. and in the Balearic Islands. "I don't like standard English, because it's very much an administrators' language. It's not funky enough, it's not got any beats to it," he says. "The kind of Scottish slang that I use is very performative. People can kind of tune into the rhythms of it. It's like with DJing, you want action to happen on every page."

Besides his unconventional language, Welsh is madly experimental in form and style. His books, especially Marabou Stork Nightmares and the short story collection The Acid House, are exhilarating in their use of graphical layouts. He separates levels of thought and consciousness on the page using different fonts, sizes, columns, boxes, squiggles and rows of words that arch up and down or form shapes. There's a whole highly academic school of writers who espouse just such an e.e. cummings approach to fiction, but Welsh says he's not aware of them. That's part of what makes Welsh so appealing--his rejection of the literary world, his estrangement from the theory-drenched avant-garde and from workshopped-to-death MFA fiction. He's something increasingly rare--a genuinely out-of-nowhere talent whose gritty, surreal, nihilistic vision comes from life, not literature. His formal daring comes from his urgency of finding ways to better convey his ideas, rather than from a hunt for postmodern gimmicks. "I want to split the page up with different textual things. People get that much more now because they're much more into visuals and graphics and images," he says. "They've grown up with it, and it corresponds to a beat. When you're dancing there's a beat, and then you get some weird effects going right over it. I try to get that rhythm into my writing, those beats and effects."

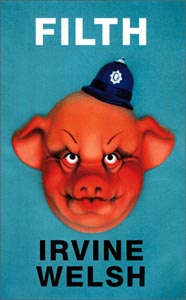

While Welsh may not consider himself avant-garde, Filth does something that few self-consciously experimental novels ever manage to do--it shocks the establishment. It was a bit thrilling to hear that police in Scotland were confiscating posters for the book because of a graphic that pictured a hog in a cop hat. "Books are like 20 years behind music," Welsh says. "The Sex Pistols were doing this 20 years ago. It's amazing that you can still get a reaction like that."

The reaction isn't unwarranted--Filth is extravagantly, gratuitously shocking, often difficult to keep reading because of its over-the-top offensiveness. Bruce Robertson makes Harvey Keitel in Bad Lieutenant seem like Cagney or Lacey. He's a racist, coke-snorting, suspect-raping, obscene-phone-call-making psychopath. His genitals are flaky and scabby with eczema, but that doesn't stop him from bedding a massive assortment of whores, friends' wives, colleagues and young girls busted with drugs. He sets up elaborate schemes to sabotage his hated boss and co-workers. He destroys his friend Bladesey's marriage, anonymously terrorizing Bladesey's wife, then playing the strong, protective policeman with her in bed. In one outrageous, hysterical, revolting scene, he tries to make an amateur porn film of a prostitute copulating with a collie. All of this while he blatantly ignores the racially fraught murder case he's supposed to be solving. Plus, he listens to Meat Loaf, Phil Collins and Deep Purple.

"I remember when I lived in Amsterdam, we used to meet a lot of cops who'd come over from Britain," Welsh says. "There's a big subculture of cops who go over to Amsterdam for the drugs and the prostitution--they have mad weekends over there. It struck me as being really ironic that these cops are forced to hassle people in Britain who are doing the same kinds of thing. You've got this kind of massive hypocrisy that permeates the society."

OF IRVINE WELSH'S three novels, Filth is the most sour and alienating. Occasionally, the writing conjures nothing so much as images of the leering author sniggering into his word processor with smarmy adolescent malice. But the book's redemption comes at the end. Throughout the novel, we're just waiting for Robertson to get what's coming to him, but when he finally does, we're so deep into Bruce's head that we almost want him to escape. Welsh creates a sick identification that borders on complicity, so much so that a disgusting police cover-up feels like a victory when it should feel like a slap in the face.

Creating identification with lowlifes and criminals has always been Welsh's modus operandi. It was easiest in Trainspotting, because Welsh's Edinburgh junkies were genuine anti-heroes, not evil, just desperate, screwed-up and nihilistic. It was more of a stretch in Marabou Stork Nightmares, which takes place largely inside the head of a football hooligan and gang-rapist in a coma after a suicide attempt. In that sense, Filth is Welsh's most ambitious book. He utterly negates our values, and then forces us to feel, if not sympathy, then at least understanding for Bruce despite his brutal, repulsive sadism.

Welsh does this largely through another one of his audacious formal devices--Bruce has a tapeworm whose own narration often bisects the page with a column that blocks out some of the other text. The tapeworm becomes the voice of Bruce's conscience and of his obliterated past, and it's through this parasite that we begin to see what made Bruce what he is.

"What I wanted to do with Bruce's character was to get somebody who seems to have no real redeeming features whatsoever," says Welsh. "Rather than create a central character or a central voice that corresponded to my values, I wanted to get a character that challenged me, who instead of affirming what I believe in actively opposes it, and then find a way to empathize with that character. Bruce is a total enemy. He hates everybody. He's quite evenhanded about it. He's looking at ways to destroy and undermine and consume people. He's a kind of vampire. I wanted people to understand where he was coming from and why he was the way he was." Without a doubt, the book will offend both those who think Welsh is endorsing Bruce's fascist views and those who don't like to see the police mocked and scorned. But, ultimately, Filth isn't just a Bret Easton Ellis-style gross-out. The moral ambiguity of Welsh's novel is as challenging as it is disturbing--paradoxically, it's both a vicious attack on the powers that be and a curiously compassionate attempt to understand a monster.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Filth

By Irvine Welsh

W.W. Norton; 320 pages; $14.

From the October 1-7, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)