![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

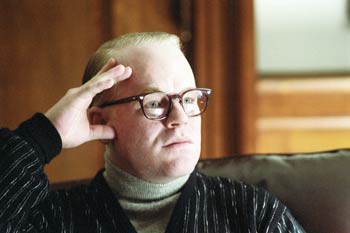

In Colder Blood: As author Truman Capote, Philip Seymour Hoffman finally finds the huge role he's been searching for.

In Colder Blood: As author Truman Capote, Philip Seymour Hoffman finally finds the huge role he's been searching for.

The Truman Show Philip Seymour Hoffman is tantalizingly eerie in new biopic of writer Truman Capote THE FILM Capote suggests that Truman Capote (Philip Seymour Hoffman) died from the complications of artistic childbirth after foaling his true-life crime book In Cold Blood. In 1959, the writer heard of a massacre in west Kansas. Four members of a blameless farm family were killed by a pair of bandits named Perry Smith and Dick Hickock. Call it a measure of how the world has changed, that the Clutter case made The New York Times. Capote phoned New Yorker editor William Shawn (Bob Balaban) to try his hand on an article about the murders. When Capote voyaged to Kansas, he brought an assistant, a writer named Nelle Harper Lee (Catherine Keener), author of To Kill a Mockingbird. In the midst of writing, the project expanded to book length; it grew intractable and hard to resolve. Thus also was Capote's odd friendship with Perry Smith (Clifton Collins Jr.). What started as a symbiotic relationship turned parasitic. Capote manipulated Smith for more and more facts, all the way to the foot of the gallows. Director Bennett Miller (The Cruise) creates a broad-scale look at the early 1960s, from the chill Kansas scenes to the Breakfast at Tiffany's-era parties, where men in dark, stiff suits hang on Capote's every word. Adam Kimmel's hand-held camera and widescreen photography visually evoke the hush and the sparseness of the past. A few breaths of music accentuate the past's remoteness--usually just some attenuated, remote piano chords. They are the perfect tones for a movie about a die-hard nostalgist. Executive producer and star Hoffman re-creates the bizarre author: the gleaming golden hair, the cream-white face, the habit of eating strained banana baby food mixed with J&B Scotch. Hoffman has mastered the writer's nasal hinhhinhhinh chuckle and the quiet but distinct Southern mutter. If a pussycat could speak, it would sound like Truman Capote. What Hoffman isn't, despite it all, is grotesque. Capote may have been a kind of monster, but he was a writer. Hoffman gives Capote credit for the artistic determination that made him steel his nerves and open the closed coffin to see the faces of the four victims. And when he's registering the perfect flatness of the Great Plains from the window of his Pullman car, you can see the writer is already at work before he's out of bed. A really distinguished movie isn't made by one central performance. The acting in Capote is of the highest quality: Collins' Smith is vastly needy, as distressingly eager to please, as Capote is eager to dominate a conversation. Chris Cooper plays Alvin Dewey, the Kansas Bureau of Investigation officer who took Capote into his home and fed him Christmas dinner, later to find out that the writer was aiding the court appeals of the man he had arrested. Cooper is one of the few living actors who can convey authority without making it look foolish or stodgy. When a man goes around self-mythologizing, as Capote did ("I'm about as tall as a shotgun and just as relentless. ... I have rather heated eyes"), he can expect mockery. "Capote's also rumored to have ball-and-claw feet, like a Queen Anne dresser," quipped S.J. Perelman, replying to the above. He can also expect a hammer attack: The National Lampoon, never a respecter of persons, costumed a skinned pig in Capote's trademark slouch hat, glasses and Burberry trench coat, using it as an illustration of their parody of Capote's Answered Prayers. Despite that roughhousing, no one previously had accused Capote of murder by negligence. Should we believe what this film has to say? Capote's act of beautifully burnished journalism earned him $2 million, and so he had motives for betrayal and possibly a source for guilt. "There are more tears shed over answered prayers" was Capote's own epitaph for his career. Those whose prayers aren't always answered can find a more common tragedy in the too-late understanding of their own motives. Capote's increasing narcissism, laziness and blockage would have found some other excuse besides the guilt of his literary treachery. Perhaps it's more likely that those familiar talent solvents, booze and pills, weakened him. Not to mention the shock of the hippie age: the nation's temporary loss of faith in the Power of Swank, which would leave an au courant courtesan like Holly Golightly hopelessly uncool. Faced with the rise of an avant-garde he couldn't understand, Capote relied upon the kindness of Merv Griffin. Regardless of its conclusions, Capote is a startlingly sinister film. In the scenes of the research interviews, Capote displays the age-old pleasures of a detective movie: the eccentric investigator whose odd methods open up suspects; the drab assistant whose clarifications keep the detective on track. In the latter role, the tremendous Keener is the film's moral sense. Her goodbye to Capote is a scene to be placed next to Valli's wordless rejection of Joseph Cotton in The Third Man. As for Hoffman, he has been for a long time an actor in search of a huge role. He's found it.

Capote (R; 110 min.), directed by Bennett Miller, written by Dan Futterman, based on the book by Gerald Clarke, photographed by Adam Kimmel and starring Philip Seymour Hoffman and Catherine Keener, opens Friday at selected theaters.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the October 5-11, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.