Image+Idea

Artist Robin Lasser creates photographic landscapes that reverberate with the context and spirit of place.

By Ann Elliott Sherman

MAKE ZOLA'S DECLARATION "live and think out loud," and it would be a fitting description of the idea-propelled work of artist Robin Lasser. One of the practitioners of digital photography selected for Pixel Perfect, the San Jose Museum of Art's current survey show, and a teacher at San Jose State University's photography department, Lasser is not your garden-variety, point-and-shoot photographer.

Lasser creates installations to be photographed in the landscape; and photographs to be installed in the landscape; and sometimes installations with nary a photograph in sight that literally reverberate with the spirit of a place. If a picture is worth a thousand words, when Lasser points the lens, many of those words will be followed by a question mark.

"I tell my students the reason that I make photographs instead of taking photographs," she says, "is that I have this need for a visceral response to something, a need to build."

The urge to build does not, however, preclude the need to think. "But I love ideas equally," she confesses. "The physical things I'm constructing are usually out of my head, usually about ideas. I don't really have any interest in building something practical. My husband is always building storage spaces and a great deck, and I'm always building something like an oil fountain."

More about Lasser can be found online, along with Andy Goldworthy.

Consuming the Landscape

LASSER'S landscape pieces are especially noteworthy because the artist possesses a knack for making the connections between a particular place and its relations to the "bigger picture" of cultural values.

In her Consuming Landscapes series, for instance, Lasser fashioned giant knives, forks and spoons out of natural materials being extracted from a particular site--burning tar and oil, say, from the Santa Barbara coast--and placed them in that landscape so that the resulting photograph is literally a place setting. The surroundings are framed into a place mat, and the viewer can have a now-you-see-it, now-you-don't experience in visual as well as intellectual terms.

Lasser's landscapes aren't an escape from everyday reality but a re-examination of it, an analytical bent further revealed in her skeptical take on Andy Goldsworthy, an artist famed for his more aestheticized photographs of natural sculptures--piles of rocks ordered in descending size, balls of twisted branches and the like--in and of the landscape.

"What's problematic with Goldsworthy's work, in relation to landscape--though as sculptures, I think they're really amazing--is that he often frames out so much of the world," Lasser says. "So you'll see his arches and all these natural surroundings, but you don't see that probably right behind it there's a building, and out from that, something else man-made, and so on."

For Lasser, Goldsworthy's highly selective manipulations of the natural world represent "a kind of privilege that began to be oppressive to me. He was in this place where he was untrammeled with the stuff that we are all besieged with, and it seemed less heroic, somehow. If he could do that in the context of some flea-bitten suburb, it would almost be more exalting."

The human as well as the natural context drives Lasser's work. "When I'm working the landscape," she says, "I feel like I'm dealing with our cultural desires--which we project onto the landscape--usurping them or resituating them so maybe there's a different understanding. [Goldsworthy is] making his art in the landscape, but in a way he isn't dealing with what's there."

Art as Interaction

NO ONE COULD accuse Lasser of avoiding the issue, even if her often inside-out approach means addressing what's long gone. This summer, the artist co-curated a show in Benecia on the fifth anniversary of forced evacuations from part of that city's Rose Drive development, which was built on a former waste site. Settling fill at the development sank backyards, ripped houses apart and exposed toxins well in excess of threshold levels.

For her part, Lasser collaborated with Peggy Dyson to stage Lamentations. Inside the evacuated house, the artists installed 13 otherwise empty specimen jars, etched with memorials to poisoned neighbors and pets. Motion-triggered computer sound chips emitted a phantom chorus of barks, cries and whispers.

Lasser remains enthusiastic about the two-way nature of the project: "The community was really involved. ... We had this whole symposium around it, and one man said the re-awakening was one of the best things that's happened in a while."

The reaction to the Benecia installation excited Lasser, because "to me, that's the best part about public art--this notion that somehow in the midst of our lives if something is slightly out of the ordinary, we might take a moment to ask, 'What is that about?' We're all aware of environmental issues, but I think we need to be constantly reminded."

The downside of public art, Lasser admits, is the time-consuming, often futile effort to get permission to do what you want, where you want. "It has to go through so many committees," she says, "and they're afraid that the public is going to take offense. So what you end up getting out there is work that--not always, but often, it's real homogenous, the same old thing."

When public art becomes predictable, "it comes back home to everybody. What we see out there and what we see in the media is what we think the world is, and what we think is right. If you do something that challenges the normative ideology, it doesn't get out there."

The result, Lasser believes, is that if we don't "fit into the normative sphere--whatever that is--then we feel shame, or we feel we're weird or we're not validated. So it's kind of a tricky arena, even though I think it's a great place to be."

Maternal Urges

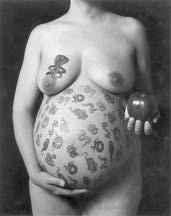

LASSER'S MOST recent photographic series, How's My Mothering, sprung from her personal experience with the vicissitudes of motherhood, is intended to appear as it did in her computer-generated mock-up: on a billboard in the urban landscape.

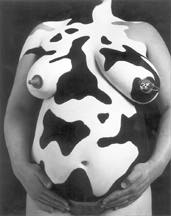

The initial piece in the series, whose impact on passing motorists might lead to gridlock, depicts three frontal views of pregnant female torsos--one is emblazoned with decals of fruit and junk food; another carries warning labels like "no smoking" and "no alcohol"; the third is painted to resemble a cow, with rubber-bottle nipples for pasties. The billboard-to-be rather pointedly asks, "How's My Mothering? Call 1 800 510 SUCK."

"The Cow Mama came from being that constant, day inday out milk machine," Lasser explains, "but there was also the sense of getting in touch with your real animal nature. Then there was the third level of before I was pregnant, dreading that body image--'looking like a cow.' "

The series, Lasser says, got her started "thinking about how my personal experience is so colluded in with a constructed cultural experience of what a mother should be and that sort of judgment on it. I wanted to do a piece that kind of took that iconography [and] used it, but tweaked it and usurped it. I don't intend the torsos to be making fun of pregnancy at all. I'm making fun of notions about it."

As for the fate of the provocative work, Lasser can't really say for sure. "I don't know if the motherhood thing will make it up there as a billboard. I really hope so, because so many women have come up to me who have seen [the reproduction], saying, 'It's just how I felt, but I was afraid to admit it,' and so on. I really want to get it out in the public venue for the reasons I talked about--not having that stuff muted all the time."

The Cow Mama exemplifies the way Lasser's work provokes both thought and laughter, a dual process that she describes as the "reverse end of the same pole" of feeling so deeply about things that you could cry.

"Some people feel in art that they should intimate, or set up a situation of discomfort with their viewer if they can, so that you're jarred out of complacency," she concludes, "but myself, I never responded well as a person that way. When I feel threatened, I recoil. So what I try to do in my teaching, and I think in my art-making process, is to invite [you] in, and once you're there and comfortable ... you know, catch you on the blind side."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

Landscape as Place Setting: Robin Lasser's "Consuming Landscapes" series of constructed photographs includes a "Mono Lake" good enough to eat.

If you ask me what I came

to do in this world, I, an artist,

will answer you:

"I am here to live out loud."

-- Émile Zola

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Maternal Matters: In "How's My Mothering?" Lasser confronts our images and anxieties about pregnancy.

Maternal Moo: More of "How's My Mothering?"

Pixel Perfect: Digital Photography in the Bay Area shows through Nov 10 at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. Market St., San Jose. Lasser's work will also appear in a group faculty show at San Jose State University's Natalie and James Thompson Art Gallery starting Nov. 19.

From the October 10-16, 1996 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art.gif)