![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

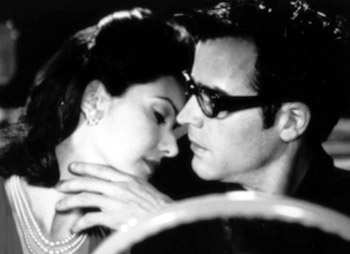

Photograph by Melissa Moseley Mulholland Maze: Even Laura Harring and Justin Theroux aren't sure what's going on in David Lynch's latest. Möbius Highway In a curlicue tale of betrayal, David Lynch sees the demons on 'Mulholland Drive' By Richard von Busack NO WONDER David Lynch called his last movie The Straight Story--it presented a total contrast to the director's usual curlicue plotting. Apart from The Straight Story and 1990's Wild at Heart, Lynch has spent his last 10 years or so creating a continuing and convoluted epic of demonic interference in human life. His newest, Mulholland Drive, an erotic horror comedy/tragedy, features Lynch's usual blindfold-and-spin method of storytelling, made all the more disorienting through his heavily saturated colors and the hypnotism of Angelo Badalamenti's music. "There is another world, but it's in this one," French director Jean Cocteau wrote. In divining this Other World, Lynch resorts to the ancient idea of humans being the prey of supernatural beings. Maybe if his actors are oddly calm, almost risibly innocent, it's because they're puppets to these forces. How does a personally conservative director indulge his tastes for the lush things of life, for eroticism and violence? By blaming it on the devil. Devils are always present behind the scenes in most of Lynch's later work. In Blue Velvet (1986), the gang members (sexually twisted outlaws led by Dennis Hopper) are so evil that they dwell on the fringes of the supernatural. The TV series Twin Peaks (1990-91) and the big-screen prequel, Twin Peaks: Fire Walk With Me (1992), leaves those fringes and heads straight into the other world. On one level, Twin Peaks is an FBI series about lethal activities in a remote Washington town. On another level, it tells the story of a demon called the Little Man from Another Place and how he pulls the strings on "Bob," the villain of the show. Lynch's Lost Highway (1997) also features a devilish "Mystery Man" (Robert Blake) with the ability to be in two places at once. His character fit perfectly with the plot of Lost Highway, which is a "Möbius strip," Lynch once said--a film that turned itself inside out, having neither beginning nor end. Mulholland Drive is more Q-shaped, a circular narrative with a short epilogue. The film is salvage work, put together from a TV pilot rejected by two networks. In the newer additions, Lynch has changed the story from a kind of Nancy Drew investigation into a tale of the fatal betrayal of two lovers. Mulholland Drive opens with a frenzied jitterbug contest, sampled, repeated and projected on a blank violet background. From a spreading haze at the bottom of the screen, two misty faces materialize: a pair of grimacing elderly henchmen in Mr. Roque's employ, spying on the dancers and selecting a girl for their use. Like most demons you read about, Roque prefers virgins. This one is named Betty Elms (Naomi Watts), from Deep River, Ontario, who wins the contest and comes to Hollywood to become a star. She arrives at LAX escorted by the two demon henchmen, posing as sweet old people. Housesitting her aunt's Hollywood apartment, Betty encounters a nude woman (Laura Elena Harring) in the bathroom. The woman, who calls herself "Rita," is the amnesiac survivor of a botched murder attempt. The two--one a complete naif, the other without memory--try to solve the mystery of Rita's identity. One of the big surprises here is a short tribute to the power of acting. Betty's first audition is a TV-movie love scene played against a walnut-tanned old lecher of an actor (Chad Everett, a 1970s TV fixture). Betty uses her body and her youth to make the canned scene come alive. After we've seen that Betty is the real thing--that she really can transform herself through acting--the movie's main theme of lost and stolen identity surfaces, and the real menace begins. Following a clue to Rita's identity, the two women discover a ripe cadaver in a locked apartment. From an innocent Snow White and Rose Red, the two transform into the mutually guilty, opposed lovers found throughout film noir. In his book Camera Lucida, critic Roland Barthes studied a picture of his mother as a little girl. He felt estranged because she was not the woman he remembered. "There is a kind of stupefaction in seeing a familiar being dressed differently. ... It was not she, and yet it was no one else." In what may be a flashback, a flashforward or a flashsideways, Betty becomes another woman. Apparently, she's the rotted dead girl, "Diane Selwyn," returned to life. Logically, Betty can't be Diane, and yet she is no one else. Thanks to the cloudy magic of identity change, we can't ever be sure who sold whom out. What's certain is that a seldom-seen character named Roque (Michael J. Anderson, the Little Man of Twin Peaks), a mute creature who lives in a huge glass tank, is the one who profits from the deed. Roque's payoff? Perhaps it's "garmonbozia" (pain and suffering), to use a Twin Peaks term: the currency of Lynch's Little Man From Another Place. Roque, like the Little Man, and like the audience, is removed from the action. He watches all, drinking in the anguish and passion of the characters. The most factual parts of Mulholland Drive seem to be supernatural. We can't tell what the demons are doing, but at least we know they're doing it. Roque's men are everywhere: they include a homeless troll behind a coffee shop, who possesses a blue box that's an interdimensional worm hole, and a frightening albino named Cowboy (Monty Montgomery), who threatens violence with a little speech about attitude. As is often the case in Lynch's work, Roy Orbison has some deep significance--is the musician meant as a portal between our world and Lynch's demon-dimensions? Robert Blake's Mystery Man, the head demon in Lost Highway, was made up to look exactly like Orbison, complete with armadillo skin, car-door ears and severely parted hair. The thugs in Blue Velvet cackle over Orbison's "In Dreams." The eeriest scene in Mulholland Drive, the one where the demon world intrudes into ours, takes place at a 3am cabaret called Café Silencio. To Betty and Rita's vast terror, a performer named Rebekah del Rio sings Orby's "Crying" in Spanish, foretelling misery to come. At the Café Silencio, musicians emote to recorded music, as if karaoke were the most satanic of the black arts. The scene hints that Mulholland Drive is about the "garmonbozia" of recorded images, sucked up by audiences who watch them. Perhaps in its complete form as a TV series, Mulholland Drive was intended to be a surreal meditation on the movies themselves. For example, Lynch has cast a living piece of MGM's golden age, dancer Ann Miller, as Betty's salty landlady, Coco. Perhaps in the longer version, Adam, a film director on the run, would have been more than the red herring he is in this version of the story. Even retooled from pilot to movie, with characters jutting out like sawn-off timbers, Mulholland Drive is as sensual, elusive and abruptly funny as a filmed dream-journal. That the mysteries of Lynch, our corn-fed Cocteau, are insoluble just makes them all the more ravishing.

Mulholland Drive (R; 146 min.), directed and written by David Lynch, photographed by Peter Deming and starring Naomi Watts and Laura Harring, opens Friday at the Cameras 1 and 3 in San Jose and the Park in Menlo Park. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 11-17, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2001 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.