![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

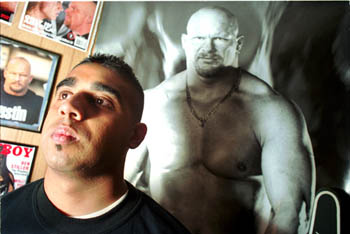

Photograph by George Sakkestad Stone Cold: Moses Sotello, 19, in the shadow of WWF poster boy Steve Austin. Sotello and girlfriend Cecelia Panis, 18, wrestle using buckets and pool cues. The two have damaged walls and a metal futon bed and won the disapproval of Mom. Backyard Barbarians Silicon Valley's backyard wrestlers take their violent obsession outdoors and powerbomb the end-product into a think tank of creativity By Genevieve Roja THIS IS RAGING BULL: furrowed brow, muddy brown eyes, sideswept grin, slicked-back fade, the build of a former championship wrestler with an added 15 pounds. This is Ruben Beltran, a.k.a. "G War," playing menace to society in wise-guy uniform: black Rage Against the Machine T-shirt with red sleeves, black track pants with a shiny silver stripe down the sides, black shoes. "Is there anyone who's going to win the belt with me?" he asks, looking around with a menacing glare. "I am," says a slender young man stepping out of the afternoon shadow. "What's up, little man? How you doin'?" says G War, who also wears a black tank top with the words "G War Machine" written on it in silver glitter fabric marker. "Pretty good," replies the more slightly built, 5-foot-6 Anthony Trevino, known to Beltran and others in their circle as Slash. Their laconic conversation comes to a halt when their nemesis, Eric Padilla, a.k.a. Evil E, a.k.a. Trevino's cousin, walks by. At his side is Steven Sanchez, aptly known as "Tank," who is built like a Sherman in terms of sheer indestructibility and size. And like almost every wrestling duo, they are shadowed by their lackey, Walter Paco, a rookie who will not tussle today. "Hold up, little munchkin," calls G War to Evil E, who has been known to incorporate dancing and breakdancing skills into his work. "Who's your boyfriend?" he taunts back. "What's all this crap you're talking about taking our belt? "I'm talking the crap," Evil E replies evenly. "You guys want a match?" Slash says, stepping up. "You guys have a match." With this decided, Trevino and Slash walk toward a still running video camera held by cameraman Adam Padilla. Then Trevino abruptly stops and starts gesturing for Adam to relinquish something. "Give me my fuckin' camera," Trevino says, pressing the "record" button to "off." Breaking the Rules CUT TO ACT II, the Entrance. Padilla is playing rap rock by some angry white male artist who thinks he's had a rough life. It lacks the rawness of a song like "Welcome to the Jungle" by Guns N' Roses, but this version of pounding metal laced with acid vocals will do for today. After standing around Shepherd Middle School on Rough and Ready Road in East San Jose, the Under Ground Wrestling Alliance (UGWA) posse emerges from behind a dumpster. Tag team by tag team, they saunter stage center, give the camera a mean snarl, then exit stage left. Soon they're rolling around in the grass, near a backstop in a field, dropkicking, choke-holding, powerlifting, doing last dances with Mary Jane, the latter being a wrestling maneuver where Trevino lifts G War off his feet and throws him onto his back, in prime pinning position. As scripted, Trevino has turned on G War and partnered with Tank from the other tag team. Earlier, Tank had dropped G War on his head, a move that nearly gave G War a concussion. Afterward, Trevino--the Vince McMahon personality of the group--fumed about the mishandling. "Fuck, dude, you broke rule number one," he lectures G War. "You didn't go over it first. That made us look hella bad." Embarrassed and disappointed that his crew screwed up, Trevino shakes his head. "For hella years, we haven't had any injuries ..." says Trevino, his voice trailing off. "Dude, dude, I was trying to get him up for a DDT," says G War, clarifying. Trevino looks G War square in the eye and spits, "Don't do shit you don't go over." Welcome to the newest backyard fight club in Silicon Valley. First rule of fight club: try and not get hurt and everything will be cool. No one wants anyone heading to the emergency room, especially with a broken wrist, a deep gash on the forehead or a black eye. Yet while this is the claim, it is not always the outcome. Note this tale from P.J. Eggers, 17, a Homestead High School junior and a member of the backyard federation, the Underground Wrestling Championship (UWC). "The only injury was Ash [Ashley Dharmaraja, a member and UWC scriptwriter], and that was his own fault; he did it to himself. He went for a dropkick and broke his wrists," Eggers says. "It wasn't an obvious break. It didn't swell up at all; it wasn't black and blue and purple. But when he went and got it X-rayed, it was broken." Eggers continues, "Minor injuries still occur, like scratches or cuts, and even once in a while huge gashes, but that only happened on one occasion and that was my own fault because I allowed it to happen to myself." "I agreed we were going to give each other kendo stick shots. I came home and didn't realize it had happened," Eggers recalls. "I checked the top of my head, and I had a huge gash about four to five inches across my head. I realized it when I washed my face and there was blood all over my face."

Photograph by Kathy De La Torre

Backyard Fever EVERYONE HAS THEIR own how-I-found-out-about-backyard-wrestling story. Moses Sotello, 19, of San Jose, saw a documentary about some kids in Los Angeles wrestling with light bulbs, breaking them off against each other the way Princess Diana once christened ships' hulls with bottles of champagne. Two years ago, backyard wrestling enthralled all wrestling fans after many viewed a now-famous underground video of wrestler Cactus Jack jumping from a rooftop in his early years. Then came the flurry of copycats. But Trevino insists they were doing backyard wrestling in seventh grade, unaware that what was merely a hobby would explode into an underground phenomenon. "Back then it was pretty basic, playing around," Trevino says. "And then we got a little more serious about it and we thought up our own names and started doing this." In cities such as San Jose and Sunnyvale, across the country and worldwide, male teenagers--and a few females--are taking their wrestling obsession outdoors and into their backyards, re-creating the melodramatic farce seen on such shows as WWF or World Championship Wrestling. Some federations, or feds, like the UGWA, take a more grassroots approach to backyard wrestling, sticking with engrossing, yet basic, mat moves and utilizing few weapons, such as a folding chair or a cane. Other feds, like the Underground Wrestling Championship in Sunnyvale, lean toward the new school of extreme backyard wrestling, maximizing their use of firecrackers, barbed wire, plywood, flaming Nerf foam bats and gasoline. Old school or new school, backyard or schoolyard, backyard wrestling has as much to do with the details of choreography and execution as encapsulating maleness and soothing the inner caveman. Oddly, backyard wrestling is also something more than a burgeoning after-school special for teenagers. It has sparked enough creativity that they are crafting scripts, characters and websites, honing organizational skills that require finding sources of revenues and farming for sponsors, ultimately transforming these backyard barbarians into entrepreneurs. Grandma's House THE UGWA WRESTLED with the UWC all summer long, practicing in a ring stationed at Eggers' grandma's house in Sunnyvale. It's sometimes hard to find a good private place to wrestle, the guys say, because so many people misconstrue what's going on. An hour before we go ringside at the Shepherd playing field, the UGWA boys are practicing moves, talking out each step. Eric Padilla practices a combination where he taps one foot right, one foot left, then flips. He comes out of the flip and swoops back up on his feet, with a clear blue, used condom sticking to his maroon shirt. The trick to backyard wrestling is to make everything look believable, spontaneous and unrehearsed, although the wrestlers confide the trick is to whisper moves to their opponent beforehand. Improvisation is encouraged, although it does have its drawbacks, as in the UGWA spectacle which cost Beltran a slight headache. That's why practicing beforehand is so important, not only to ensure that accidents don't happen, but also to ensure that the name of backyard wrestling isn't completely tarnished. So UGWA members such as Portillo teach how to cushion falls, shoulder blows. "The main thing is, when you land, you have to land on a large part of your body so it doesn't hurt," says Portillo, who taught Trevino how to wrestle. "'Cause if you just land on your elbow, you're gonna feel that. Mostly the pain doesn't come during the match. It usually comes ..." "The day after," says Trevino, finishing his sentence. "During a match you don't feel it. It's like any sport." But after hammering on one another, sometimes in mock play but still landing a few kicks, holds and punches, can backyard wrestlers still be friends in the morning? "After every match we tell each other, 'That was a good match,'" Eggers says. "If we weren't such good friends, it would probably result [in] anger or resentment [toward] each other. But we all know that everything we do is in front of the camera. Behind the camera, things are so much different."

Tight Squeeze: 'G War,' a.k.a. Ruben Beltran (right), struggles to lift his opponent 'Tank' (left), off his feet. UGWA wrestlers are taught how to properly land in order to avoid injuries. Out of the Cave WATCHING WWF, or its amateur spawn, leaves room to ponder where, evolutionarily speaking, we have landed. Mary Larson, a professor at Northern Illinois University who has studied television, children and families since 1985, says the thrills of Fight Club and its fans aside, the notion of sparring as an outlet is dubious. "Perhaps it can [ease stress] in the same way that learning karate can do it, but as far as I know backyard wrestlers are practicing moves that can get people hurt, and that's a heavy price to pay," she says. The wrestlers here--and elsewhere--would disagree. There's a moment in Fight Club when Edward Norton's character explains the aura behind fighting. "After fighting, everything else in your life got the volume turned down," he said. "You could deal with anything. Most of the week we were Ozzie and Harriet. Every Saturday night, we were finding something out. We were finding out more and more we were not alone." Patty Eggers sometimes holds her breath as she watches her son and his friends backyard wrestle in her mother's yard. But she makes no mention of any mishaps; instead she says that it's nice to see her son making friends, writing scripts, helping revamp the website (www.uwcunderground.com). "He's got some nice friends, and he's met the boys from San Jose, and they seem to get along pretty darn good," says Eggers, a single mother and longtime employee at Hewlett-Packard. "That's social skills out there." And the violence, well, she says it's all fake. "Nothing's more fake," Patty says. "It's all choreographed--who's going to do what, who's going to play which part. It's not real." Patty, who says she was "real rough and tumbly" growing up, claims that her son and his friends are merely play-acting out there, arching their eyebrows like The Rock, or flexing their post-pubescent muscle. To believe that P.J. and the others have an agenda to maim someone intentionally and seriously is simply out of the question. "I've seen basketball games that are more violent than what they do," says Patty, who has accompanied P.J. to WWF shows at the Arena, the Oakland Coliseum and the Cow Palace for several years. "The players get angry and get aggressive back. But not these guys. I've seen what they do; it's all mimic." Given the violent nature of backyard wrestling, it might be easy to label all of its fans as violent, emotionally disturbed and troublemakers. But they insist this is not the case. "Outside of wrestling, I don't like fighting," P.J. says. "I know for a fact I used to be angry at a lot of things 'cause my grandfather died. I used to get mad easily, but I saw how it affected not just myself but my friends, so I completely stopped." And that has made all the difference for P.J. and his wrestling buddies. "I don't think any of our wrestlers are violent outside of wrestling," P.J. says. "I think they're good-hearted. At school, we're just happy-go-lucky people." Eggers adds, "We've trained everyone to appear that we really do have hatred toward each other, ranging from the language, some of the moves that we do to each other. Sometimes we'll have gratuitous language used toward another wrestler, but aside from the camera, what the camera sees, is the complete opposite." Character Studies PERHAPS THE MOST prominent feature of any kind of wrestling is a wrestler's name and the persona that goes with it. Got a name, get a life. In assessing He-Man, for example, one can say he is blonde, tanned, beefy. Wears a loincloth and shaggy brown boots and carries a long sword. Likes to raise a sword in the air and proclaim he's got power. So after finding out what works, what doesn't, a backyard wrestler decides who he will be. Is the character dark or brooding or is he better suited to be the audience's fool? P.J. settled on dark character Paranoia, who, like him, didn't like speaking with a microphone. Originally named San Quentin Prisoner 23, Eggers changed the name, after the song "Paranoia" by Paper Chasing Organization (PCO). He makes his entrance with music by Rob Zombie and makes his mark wearing a T-shirt from Papa Joe's tattoo parlor, which he and Mike Mullen visited last summer. True to wrestling showmanship, Eggers dons black makeup that he says adds to his character's mystique. "I put on makeup because most of the matches I wrestled in as San Quentin, I'd give interviews and I'd give a darker, shadowy effect [with the makeup]," Eggers says. "I put the stuff on my face without a specific design [except it was] like The Crow, like Brandon Lee. But I needed to change that because there were too many people with that face paint, so I painted my face like Alice Cooper." Voilà. A renegade character for the soap opera was born. Eggers explains his character's personality traits. "Nobody likes me, I beat the crap out of whoever doesn't like me. I use a lot of foul language. I use it all the time; I use weapons; I'm in the most violent matches." Eggers has three masked characters, meaning that the characters never reveal their faces, or for that matter, their true identity. Of those three--Hellspawn, Static and Julio Semen--the latter character is by far the most amusing, and the most telling. Eggers says he has a problem with all the Latin lovers like Ricky Martin and Enrique Iglesias combing their way through MTV's Total Request Live and America's record charts. "I think all Spanish music is too hyped," he says. "Thousands of people pay money to see [Spanish-speaking musical groups] dance crappy on TV." His other dislike: breakdancing. So when Julio Semen takes the stage, the product is a hybrid of breakdancing, crappy dancing, hip shaking and general mocking. The character is strictly a jester for the audience, and a surefire loser against other wrestlers. "He always loses because he wants to mock the crowd and dance," Eggers says about his wildcard character. "We put him in because he pushes the other wrestlers' ranking up." Being funny is the easy part. Finding a place to be funny, to do moves and not get caught by police, is the tricky part. The UGWA discovered that wrestling on a grassy patch on the premises of their local Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints wasn't an ideal spot, despite the blessing of officials there. Convinced that they were witnessing a brawl and not a jovial mock match, neighbors called the police and demanded they close shop. The UGWA's present location is still very public, in full view of jog walkers and parents bringing their sons and daughters out to play catch. No one says a thing; one jog walker smiles politely at the boys as he completes each successful lap.

Giving a Kind Boost: 'G War' arches his back to dispose of 'Tank', who minutes later gives 'G War' a near concussion when he drops him on his head. Homemade Horror IT'S FRIDAY NIGHT, and I'm watching the mayhem unfolding on Best of Backyard Wrestling, which is intriguing at first, then tumbles down the slippery slope. For $19.95, it's really a poorly filmed compilation of homemade video outtakes from backyarders nationwide. On this video, wrestlers pick up anything and it's a weapon: bales of hay, an ironing board, a trash can, a chair, a crutch, even a guitar. Trampolines and roofs are merely springboards to dive feet first or belly down into a writhing opponent. For added excitement, some wrestlers are set on fire. In between segments titled "Get Prepared," "Fire" and "Groin Pains," viewers are teased with a shot of the backyard ring girl, Tylene, in all her fake breast glory, wearing nothing but a cut-off T-shirt around the bust and the obligatory Daisy Dukes. Apparently, there are movie buffs, with one group's submission of Speed 3. "More fun than my dad's porno collection," raved one satisfied viewer. I particularly loved the chubby 9- or 10-year-old boy, wearing a Darth Maul plastic mask, saying, "I don't need a fuckin' entrance." Oh, and if anyone is bloodied from being whacked in the head with a garbage can or caught in exploding barbed wire, the bigger the cheer. Death-defying wins here, hands down. For in backyard wrestling, the sometime rule is to make your stuff look flashier, more hard-core, more titillating than what you'll see in an episode of WWF, hence the artillery involved. "We'll use barbed wire bricks, barbed wire hockey sticks, barbed wire bats--whatever it takes to make it look better than what's on TV," Eggers says. This coming from a person who denounces fights on television on shows other than wrestling ones, and thinks "boxing is a brutal sport." He says this because he knows the difference between what is fake and what is real--an argument that nearly every backyard wrestler I talked to made known. "We mimic what we see on TV ... but most people in general can tell what's going to hurt someone and what can end their career as a wrestler," says Eggers, who plays baseball for Homestead. "I believe that most people can see what is right and what is wrong." And that distinction may be why even the hardest of the hard-core wrestlers don't go as far as their professional counterparts in wrestling feds in Japan or Mexico. Eggers says the Japanese show, aired on a local Asian television channel, is one of the roughest he's ever seen. "They use live electricity, throw each other on it," Eggers says. "There'll be thumbtacks, nails, railroad spikes. I believe there's been over a thousand deaths in Japanese wrestling. And Mick Foley lost an ear and I believe Terry Funk lost a toe in Japanese wrestling. He's also one of the other people I look up to." Love Bites CECELIA PANIS, 18, and Moses Sotello, 19, are proof of the old adage about hurting the ones you love. It just kind of happened, they say. Both avid wrestling fans, Cecelia and Moses began play-fighting until the roughhousing reached full tilt. Their roving backyard fights--now curbed--led to a broken futon bed and gaping holes in the wall. "It started in my room, to the living room, to outside, to out by the side of the carport, to chasing each other down the street with pool sticks," says Sotello, whose daytime job involves working with children in San Jose. "People wonder what we're doing." Indeed. "My girlfriend and I wake up with all kinds of bruises and shit," admits Sotello. In the last year, Panis and Sotello--both avid wrestling fans--have poked each other with broomsticks, buckets and plywood. The one time she balked involved thumbtacks, which are scattered onto the floor. The wrestlers then wriggle away on the surface. "No, but it gets me mad," Sotello continues. "My mom thinks I beat up on her. She doesn't know that it's like ... sometimes she [Panis] swings at me hella fuckin' hard." Reminding Sotello that that comment is quotable, he only shrugs, not in defeat, but in acceptance of the truth. "It's fun to see who can beat who," says Cecelia, a student at Heald College who is learning business software applications. And who wins? "Him," she says, laughing. She says there is no anger involved, and she never hits with malice. "We're just playing around," she says simply. "I put him in holds where he can't get up. It's fun because we just laugh about it after." She is pensive when I ask her why backyard wrestlers go to such great lengths to achieve this level of fun, or fright. "They do it because that's what they like," she says. "People hold them back so much, they do what they want to." And because wrestling, next to his girlfriend, is where Sotello's true passions lie. "Once she saw my room, she knew that it was my whole life," he says. "We'd start watching [wrestling shows] together; that's how it all came about. Even if we're just lying in bed, that's all I'm talking about. Anything we do, it has to do with wrestling--even if we're eating, it's like, everything."

Blister in the Sun: (L to R) Lackey Walter Paco, 'G War Machine,' 'Slash' and 'Tank' watch 'Evil E' practice his signature move, the head spin. Later the group laughs when he does a flip and lands on his feet with a used condom sticking to his T-shirt. All Things Green SOMEWHERE, out there is a pipe dream, a ticket to the pro wrestling circuit. Eggers' Paranoia can see the bright lights of coliseums nationwide, a dark character so beloved, so admired, that little kids look like mini Alice Coopers. He'll invent some remarkable catch phrase even more inventive than "Suck it," and the wrestling world will be under his spell. Then the pinnacle of effective marketing: a Paranoia doll, barbed wire kits safe enough for kids, barbed wire bats. Maybe his dark side will be sexy, and maybe that will entice some triple-D beauty into becoming his wrestling woman, a woman far more superior than Miss Elizabeth was to Randy "Macho Man" Savage. Everyone holds tight to this dream, including Eggers, Mullen and Ash. Eggers says the group feels so strongly about this pursuit to go pro that the trio has forged a pact. They have pledged never to forget one another if one of them breaks through the professional wrestling ranks. "I've loved wrestling ever since I was a little kid," Eggers says. "I've watched it forever; I've wanted to be a wrestler for as long as I remember. Not only do I think it's a good experience [backyard wrestling], but it's brought all our friends closer together." And though making money isn't necessarily the centerpiece or the reason behind backyard wrestling, it doesn't hurt to try. Last summer, Mullen--who designed the UWC website and is transferring videotaped matches onto the site--charged backyarders a $20 ring fee, to "keep the ring in shape," he says. And with several hundred backyard feds on the web, UWC has distinguished itself by making the site interactive, polling visitors about which match-up they'd like to see. Trevino, ever the shameless promoter, sells the UGWA homemade tapes to his classmates for $7 a pop, or $10 for two. "I couldn't make a living selling tapes," says Trevino, who plans to study business at De Anza College to help him with his future occupation as a promoter. "So far I have three people that want to buy a tape." In England, Dan Thompson, a founding member of Gargrave Wrestling Alliance, solicits money by asking patrons through the website to sponsor a wrestler. The funds will go toward improving a backyard ring that is currently "getting old and battered." Sponsors commit to spending £2 ($3) a month by buying a GWA homemade video. Even the entertainment industry--never hesitating to capitalize on a slice of quirky pop culture--has caught on to backyard wrestling's marketability, with the yet-to-be-released film Backyard Dogs. And of course, who could forget to include the ubiquitous Best of Backyard Wrestling volumes, which should find their place between Girls Gone Wild and Best of Jerry Springer. Whether backyard wrestling is sport reserved only for jackasses and adrenaline junkies, it's inevitable that someone's ass will get kicked. Misery, after all--albeit misery contrived and constructive--loves company. "This is something we all like to do and it brings us together," Trevino says. "But a lot of people think we're stupid for doing it. But would they rather have us doing this or would they rather have us out in the streets ... smoking and drinking and doing a bunch of bad things?" [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 12-18, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

A Kick in the Head: Under Ground Wrestling Alliance (UGWA) promoter Anthony Trevino, a.k.a. 'Slash,' flies over the head of 'Evil E,' a.k.a. Eric Padilla. Trevino's and other federations draw inspiration from many wrestling federations, including a popular Japanese one that features men losing ears and toes in defeat.

A Kick in the Head: Under Ground Wrestling Alliance (UGWA) promoter Anthony Trevino, a.k.a. 'Slash,' flies over the head of 'Evil E,' a.k.a. Eric Padilla. Trevino's and other federations draw inspiration from many wrestling federations, including a popular Japanese one that features men losing ears and toes in defeat.