![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

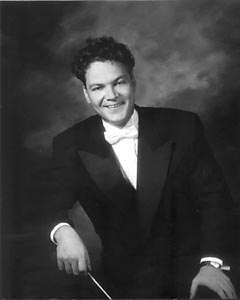

Framing Lincoln: Conductor Yair Samet tried to match music to narration in Copland's 'Lincoln Portrait.'

Framing Lincoln: Conductor Yair Samet tried to match music to narration in Copland's 'Lincoln Portrait.'

Coping With Copland The San Jose Symphony devoted its attentions to the bucolic sounds of Aaron Copland By Scott MacClelland YOU COULD ALMOST SMELL the cedars of Lebanon in the pastoral music of Aaron Copland last Saturday at San Jose Center for the Performing Arts. On the San Jose Symphony podium, Israeli-born Yair Samet somehow found honey, almonds and dates in the composer's Appalachian Spring. Under the conductor's liquid phrasing, spring turned into summer, the better to release these perfumes. The wind players, in particular, seemed to feel quite at home in this atmosphere. Languorous moments like these, soft-spoken and sensuous, struck a palpable contrast between Samet (San Jose State University assistant conductor) and the orchestra's more impatient music director, Leonid Grin. So vivid was the difference, it became possible to imagine assigning some repertoire to one while reserving the rest for the other. A southern summer--in Knoxville, for example--also infused Copland's Clarinet Concerto, one of the great works for the instrument and, thanks to the beguiling soloist David Shifrin, the highlight of this all-Copland centennial program. Some classical clarinetists avoid vibrato at all costs. Shifrin considers vibrato as simply another component of expression and used it effectively if sparingly. But unlike another highly acclaimed virtuoso of the instrument, there was nothing precious about Shifrin's playing. Alternately, he swayed and strode, he shouted and whispered. He fearlessly exposed all the tricks of his trade and still left the mind wondering how he did it. Most of his fireworks were packed into the big solo that separates the dreamy first movement from the jazzy finale. In significant ways, Copland never returned to the style and character of this Benny Goodman commission. Happily, Shifrin did, filling the CPA with waves of voluptuous sound. These days, Appalachian Spring is getting increasing exposure for its original version for 13 instruments. In it, the ear will recognize Copland's uncanny feeling for the rural farmland as conceived by dancer Martha Graham. The fully orchestrated concert suite, by comparison, belongs in town. Even while Samet made room for bucolic musings, the big edition retains an urban slickness that seems almost self-conscious. (Like it or not, Copland gave American concert music its rural character, even while he himself once described English composer Ralph Vaughan Williams' pastoral Fifth Symphony as "like looking at a cow for 45 minutes.") Samet's program boomed somewhat clumsily through the opening Fanfare for the Common Man, then gained redemption in El Salon Mexico, which provided his first opportunity to broaden the pace in favor of humid solos by clarinet, flute, cello and violin. The hero of San Francisco's Glide Memorial Church, Rev. Cecil Williams, should have been an ideal choice to narrate Lincoln Portrait, but through no fault of his own, it didn't work out that way. Except for one conspicuous full stop, Copland's score requires a skillful match-up between spoken passages and musical phrasing. For all their efforts, Samet and Williams kept missing the connections. The narration either ended to early, or too late; the salutary outbursts by the orchestra either exploded over the spoken words or seemed to punctuate nothing in particular. This of all narration pieces needs the kind of coordination that can only be achieved through sufficient rehearsal time or well-understood cues. Obviously, that didn't happen here, stranding the piece short of its intended impact. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 12-18, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.