![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

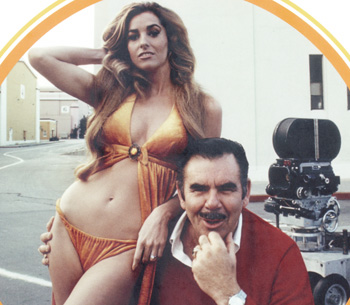

All the Vixens: Director Russ Meyer knew what audiences wanted: titanic females and muscle-bound blockheads. Mammary Man A new biography of soft-core exploitation director Russ Meyer gives the king of rack & roll an overdue tribute THE HINGE of director Russ Meyer's career came around 1970. His film Vixen set the still-standing record for all-time longest drive-in engagement with a nearly yearlong run. Hollywood had caught up to the renowned indie director, and 20th Century-Fox had signed him to a three-picture deal. His latest opus was Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, scripted by an eager-beaver Chicago film critic named Roger Ebert. The picture captures the hysteria of late-1960s Hollywood—those "Scotch drinker's ideas of the psychedelic," in critic Michael Monahan's phrase. Meyer was a star at the first film festival held at Yale. Critic Richard Schickel compared Meyer favorably to Walt Disney. The director capped his success with marriage to the exotic dancer Edy Williams and the purchase of a new house in Coldwater Canyon. This Northern California native was riding high. And he was very much a local. Oakland-born, Stockton-buried, Meyer nursed a longtime whim to re-create on film one of his earliest memories: a visit to the since-gone Alum Rock Park mineral-waters gazebo. It was to be a tableau worthy of Chagall—his mother holding up his infant self to the fountain and a guardian angel watching over him from a tree branch. Topless, of course. For Meyer, the big time evaporated after two flop movies and a splashy divorce. Most importantly, his peculiar craft was in decline. Hard-core porn pushed out the above-the-waist exploitation filmmaking that Meyer had pioneered. In his biography, Big Bosoms and Square Jaws, Jimmy McDonough charts Meyer during the residual years and the last sad, sordid days. First, the old man was roughed up by his latest starlet, Melissa Mounds. Then he sank deep into incontinent senility before succumbing to a killer lady named pneumonia. "Cartoon doesn't mean wrong, it just means larger than life," McDonough quotes Raven de la Croix, one of Meyer's stars. In almost two dozen movies, in either violently stark black-and-white or high-contrast color, Meyer illuminated the clash of "the pneumatic woman and the stupid man"—most memorably in 1966's Faster Pussycat! Kill! Kill! Never a success in its time, this miracle of dyke-noir is Meyer's most popular work today—a saraband of titanic females, muscle-bound blockheads and cracked geezers, staged on a gleaming playa. Sam Fuller is one model for Meyer's filmmaking. So is King Vidor—Bette Davis writhing on her bed, soaked in reflected flames in Beyond the Forest, or Gregory Peck and Jennifer Jones emoting away in their kiss-and-kill death scene in Duel in the Sun. Duel in the Sun: now that's a title that could be used for any Meyer melodrama, shot under heat-and-light-focusing aluminum reflectors. But Meyer went more berserk than either Vidor or Fuller. The director told me in a 1985 interview (which McDonough quotes), "My feeling is that my movies are fleshed out cartoons. ... People are clearly a good lay or a bad lay, a good guy or a bad guy, there's no shadings between them. ... I think it hies back to the time of 'Aha, me proud beauty.' The engine is approaching, and Jack Dalton is the hero's name and Tess Trueheart is the girl." McDonough, author of the Neil Young bio Shakey, has done champion work. He never goes overboard with special pleading for Meyer's greatness, never stirring up artificial angst when the real thing will do. Venal and fetishistic as he could be, Meyer did indeed have worries. Real or perceived betrayal was the worst sin in his eyes. McDonough dug up a wild tale of how Meyer shunned longtime collaborator George Costello for handing Erica Gavin a can of grapefruit juice during one 110 degree shoot. Presumably Meyer wanted Gavin's thirst to radiate onscreen. Gavin—the star of Vixen—is quite gracious about the way she was treated. McDonough says Gavin even admires Meyer for understanding the tigerish nature lurking underneath the frightened girl she was so long ago: "Russ sees your subconscious and has you become it." In person, Meyer was every bit as gregarious as McDonough describes him. Though he was as megalomaniac as Otto Preminger on the set, he could turn it off when he was having a couple of Bud Lights in his house near Lake Hollywood. He loved being Russ Meyer. His bearish good humor was counterbalanced by an unhappy personal life: strife-filled marriages, an institutionalized sister and a dominating mother, who had no use for her son's big-chested "cows." Yet these private woes rarely broached the surface. "One of the great things about him was that he just didn't give a fuck," McDonough writes about Meyer. The description of Meyer's "marvelous mind" is just about right. True, Meyer mocked intellectuals and "Red shmucks." He was a reflexive if unconvincing homophobe and a rock-ribbed patriot. Who wouldn't be a blind patriot if America meant what Meyer understood it to mean: big, bad amoral girls, fast cars, wide-open spaces and a teary reverence for the soldiers of the Big One? Meyer was no barbarian. He clearly based The Immoral Mr. Teas on Tati's Mr. Hulot's Holiday. His pal Ebert, cowering under the pseudonym "R. Hyde," merrily ripped off Thornton Wilder's Our Town for Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens, just as the rotund critic had previously lifted verse from imagist poet "H.D." for narration in Meyer's Up! Although he is a solid reporter, McDonough also captures more subjective stuff regarding the brashness and vitality of Meyer on film. He is particularly apt in writing about 1979's Beneath the Valley of the Ultravixens, in which the girl-bomb exuberance of Kitten Natividad is like a big lungful of nitrous oxide. Peering through walls and looking from under the bedsprings, Meyer scopes the archetypical small town in fresh, morning-in-America hues. It's a prelude to the cinematic fantasias of the Reagan years, cut with half-kidding and half-serious odes to racial brotherhood. McDonough characterizes Ultravixens accurately in two ways: as both a movie one ought not to live without and as a Ferris wheel out of control. The book urges that Meyer's legacy must be reissued. Technology exists to give Meyer's films a much-needed polish. The cover graphics currently used are as cheap as the illustrations on the DVDs in the Walgreen's remaindered bin. Lastly, the RMfilms.com website is still waist-deep in 1995. Meyer mused that he could have been a great director if it weren't for his bosomania. He needn't have had second thoughts. My favorite story in the book is how the director actually climbed the ladder to put the letters on the marquee at one Chicago theater. One of the last times I saw Meyer he was carrying his own film cans and dropping them into the trunk of his Cadillac parked on San Salvador Street. There are hardly any marquees big enough for the likes of Meyer, and the pictures seem much smaller since his demise.

Big Bosoms and Square Jaws by Jimmy McDonough; Crown; $26.96; 463 pages.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the October 12-18, 2005 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2005 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.