![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

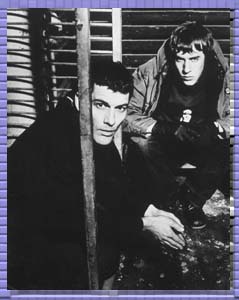

Closing the Loops: Musical forms emerge in the hands of Death in Vegas.

Closing the Loops: Musical forms emerge in the hands of Death in Vegas.

Visceral in Vegas Death in Vegas fuses electronica and rock on 'The Contino Sessions' By Michelle Goldberg EVER SINCE Prodigy's bombastic brand of rave & roll propelled the band into international pop fame, rock has been informing the electronic music mainstream. With Blur's monumental 13, the possibilities of rocktronica hybrids were radically expanded--suddenly, instead of rock conventions making techno digestible to the masses, electronic music's manic formal experiments were influencing guitar bands. Ironically, by weaning a generation's ears away from the verse-chorus-verse structure, electronica paved the way for a resurgence of psychedelic rock. Death in Vegas' The Contino Sessions (BMG/Time Bomb) follows in the experimental footsteps of 13. Although there are techno effects on The Contino Sessions, it's undoubtedly a rock album, heavy with feedback, crunchy guitar licks and sneering vocals. But the album possesses the amorphous quality of electronica, full of tangents and jazzlike variations on a theme, loops and sprawling soundscapes. At its best, The Contino Sessions recalls the visceral unease of the Velvet Underground's droning codas. Many critics and fans alike regard electronica and rock as diametric opposites locked into some kind of battle for pop supremacy, but for years now, the two have been fusing. The best albums have always been stylistic mongrels, from Elvis' merging of white country and black blues to Massive Attack's brew of soul, hip-hop and indie rock. Death in Vegas is, needless to say, not on a par with either, but The Contino Sessions does point the way toward a similarly exciting genre synthesis. Not surprisingly, the most electrifying song on the album is the one that features Iggy Pop guesting on vocals, "Aisha." The music is a swamp of buzzing, discordant guitars and urgent percussion, occasionally overlaid with menacing keyboard melodies. Against this troubling backdrop, Pop growls a tale about a serial killer. He's singing to a girl, and his story is half warning, half threat. "Aisha, we've only just met, and I think you ought to know, I'm a murderer," he says in that inimitably sultry, scary baritone. Then he turns the story around, makes himself seem the victim. "I have a portrait on my wall. He's a serial killer. I thought he wouldn't escape," Pop sings, before confiding in a tortured groan, "Aisha, he got out." Like Blur's 13, the power in "Aisha" derives from the way it anchors the hazy formlessness of the music with the narrative thrust of the lyrics. Indeed, one reason why electronic music and rock seem to need each other so much is that while rock's forms have grown stale, the human voice never becomes obsolete. Other tracks feature vocals from Primal Scream's Bobby Gillespie, Dot Allison and the Jesus & Mary Chain's Jim Reid. Still others are vocal-free, and without a singer to provide a point of identification, the meanderings can become monotonous. An exception is "Lever Street," in which an organ trills bittersweetly over a plaintive guitar while a haze of feedback lends the whole thing a watercolor quality. The organ and the guitar work together like dancers, harmonizing and then splitting up and going their separate ways. "Lever Street" evokes an autumnal beauty and a sharp sting of regret that are all the more remarkable because they are achieved wordlessly. But the right words can heighten the emotion immeasurably, as "Aladdin's Story" demonstrates. The mellow, rolling guitar and keyboard melody have just started to grow tedious when a rich, soulful voice appears, crooning a snatch of hymn. "Nobody knows the trouble I've seen, nobody knows the sorrow," the woman sings jauntily, in a voice that forecloses self-pity. A choir comes in behind her (the arrangement was done by ethereal trip-hop chanteuse Dot Allison), but subtly, so that the song is uplifting without being weighed down by the melodrama that marred Blur's similar "Tender." Instead of pathos, "Aladdin's Story" comes tinged with both funk and divinity. LIKE ELECTRONIC MUSICIANS, Death in Vegas uses layers of sound. Rock is mostly oriented forward, toward the next verse, the next chorus, the next song, while electronic music's use of repetition makes it seem less linear. Instead, electronica delves into depth and atmosphere. That's also true of The Contino Sessions. The album's opening song, "Dirge," works almost like a dub track, with guitar lines and Allison's vocals emerging in the swampy mix and then falling out, the whole thing thick with spacey reverb. Similarly, the song that follows it, "Soul Auctioneer," takes its cues from hip-hop, with Gillespie's voice syncopated with the deep bass and the whining bursts of guitar sounding almost like samples. Occasionally all the layers are just muddy, the morass of churning guitars forming a kind of sonic black hole. The dense jumble of "Broken Little Sister" is almost impenetrable, taking the swirling storm of guitars that marked the Jesus and Mary Chain and turning it into a tornado. Similarly, the rough strains that repeat on "Death Threat" are deathly boring for several unchanging minutes, until, near the end, it expands into a freeform barrage. In spite of the repetitive bits, though, The Contino Sessions delivers an often brilliant departure from the clichés of both pop and electronic music. It's a trip with lots of detours, but the ultimate destination looks like the future of rock. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 14-20, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.