![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

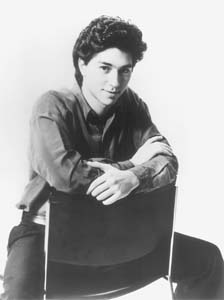

Baby-Faced Grand Pianist: Sergio Tiempo, 29, was the featured soloist at a San Jose Symphony program that celebrated the exuberance of youth.

Baby-Faced Grand Pianist: Sergio Tiempo, 29, was the featured soloist at a San Jose Symphony program that celebrated the exuberance of youth.

Dizzying Schubert The San Jose Symphony whirls through dramatic reading of Schubert's 'Great' By Scott MacClelland THE LONGER it lasted, the shorter it got. Riddle or illusion, that's what's supposed to happen in Schubert's Great C Major Symphony. Surprisingly, it rarely does. But in last Friday's reading, the San Jose Symphony found itself increasingly pulled into the spinning vortex of this bewitching work. At last, even Leonid Grin, for all his podium conduct, was secured in orbit by the same gravitational pull. The point of no return would be the final movement, the work's dizzying perpetual motion, its ultimate whirling dervish. (In fact, the piece was so far ahead of its time that its example would not surface again until Bruckner took up the cause in his own symphonic essays more than three and a half decades later.) But for it to have hit that stride with such centrifugal force means that the orchestra had established its commitment much earlier. Grin set the tone at the outset, wisely resisting the temptation to allow the andante introduction to accelerate (as happens with inexplicable frequency under numerous conductors). This strategy gave the sudden shift of gears into the allegro the dramatic impact Schubert intended. In the meantime, Grin subtly shaped phrases and scaled dynamics, creating tensions that heightened expectation as the work unfolded. Despite its wealth of melodies and its startling turns, there remains a "how many ways can I say the same thing?" quality to this work. Many have remarked on its length. It defenders have answered "heavenly length." Schubert tried to hurl his javelin as far into the future as he could. It almost seems the 30-year-old composer struck a deal with the devil. When the work gets a reading as good as this, one begins to wonder who is heaven's best salesman. This entire program was a celebration of youth. Schubert was only 30 (and on death's doorstep) when he composed the Symphony in C. Chopin was 20 when his Piano Concerto in E Minor was heard in public for the first time. The soloist for this concert, the Argentine pianist Sergio Tiempo, is now 29. His performance was brilliant, impulsive and explosive and brought the audience to its feet. But for all its thrills, the Chopin lacked grandeur. The long, soaring melodic lines that reflect the composer's keen interest in Bellini were not in Tiempo's vocabulary. For all its youthful impetuosity, the playing was more pianistic than poetic. Tiempo began performing in public as a child. One had the nagging feeling that this young man's dazzling technique was overdue for passage into greater artistic imagination. Michael Abels was 35 at the premiere of his Dance for Martin's Dream early last year in Nashville. (He turned 37 at this performance, signaled by Grin and the orchestra's "Happy Birthday to You.") The work itself, a tribute to Martin Luther King Jr.'s famous speech at the Lincoln Memorial, displays a keen organization that alternates slow and fast, quiet and loud, and explores a variety of effects (none more unusual than having the musicians speak in rhythmic patterns) and styles. While the program notes refer to bluegrass, funk, salsa and rap, none of these makes more impact than spice in a grander recipe. The 14-minute piece opens with a Hovhaness solo trumpet, then gives way to syncopated dances and vividly orchestrated crescendos. At its busiest, the piece takes pinches of minimalism from John Adams (The Chairman Dances) and refractions from Michael Torke's color pieces. Abels also flatters the musicians with various solos, which, as it turned out, were only the first of many that enjoyed polish and grace throughout the evening. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 14-20, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.