Christopher Gardner

Future Past: The San Francisco Bay Area--including the South Bay--was once a green carpet of the largest wetland habitat on earth. Because of infilling and development, only 10 percent of the wetlands remain.

The battle over the San Francisco Bay's largest remaining unprotected wetland

THE BEST WAY to see Bair Island in its natural state is to take a boat up Redwood Creek to the outer island, separated from the middle island by meandering Corkscrew Slough, a waterway that varies in depth from a few inches to more than 11 feet at high tide. Whereas dikes and siphons keep the two inner islands high and dry, parts of the outer island flood with the tides while others stay dry, providing varied habitats for harbor seals, herons, egrets, hawks and the bay's clapper rail.

Low tide came and went from Corkscrew just before noon one sunny day last October when Ralph Nobles set out to inspect the treasures of Bair Island, invisible to the traffic rocketing by on Route 101.

He borrowed a shallow-draft, inflatable motor boat from the Marine Science Institute, an education and research center near the port of Redwood City. After motoring up Redwood Creek, he turned left into Corkscrew; the propeller occasionally churned the bottom, leaving a wake of muddy clouds.

The banks of Corkscrew are punctuated by "haulouts"--areas of matted picklegrass, a succulent saltwater plant, where harbor seals pull themselves out of the bay to absorb the afternoon sun. Alarmed by the insistent sputter of the nine-mule Evinrude motor, the seals began to bark and flop anxiously toward the water. Unlike their cousins, the sea lions that clown for tourists 30 miles north at San Francisco's Pier 39, these seals were unaccustomed to human visitors.

"Sorry to disturb you," Nobles said, standing up in the boat and peering through a pair of binoculars. "Resume your naps."

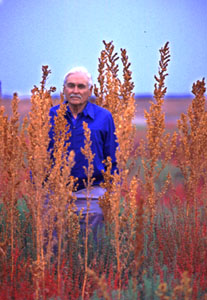

Old Man and the Bay: Retired physicist Ralph Nobles has made protecting Bair Island from development a personal mission for the past 14 years.

Photo by Christopher Gardner

Nobles' Cause

ENVIRONMENTAL activists crowded the conference room at the Peninsula Conservation Center on East Bayshore Road in Palo Alto one evening last January. Their featured speaker, Nobles, took the microphone. A white-haired, retired nuclear physicist, Nobles, 75, has worked for the last 14 years to prevent housing and commercial development on Bair Island, a 3,000-acre tract of islands and tidal marshes, twice the size of the Presidio, in the southern portion of the San Francisco Bay.

Nobles shared a story about how he told U.S. Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt, during his visit to the area last December, that Bair Island--one of the last specks of wilderness left in the San Francisco Bay--serves as an irreplaceable refuge for dozens of wildlife species. He urged Babbitt to do all he could to help prevent a Japanese-owned development firm from building a new suburb on the habitat.

"Before I came here, I had never heard of Bair Island," Babbitt said, addressing a crowd before flying back to Washington, D.C. "Now, I will never forget it."

The story brought smiles and clapping from the 82 activists who packed the room, a reaction Nobles elicits when he tells the same story to mobilize dozens of similar activist groups throughout the Bay Area. He is an ancient warrior--a general, in fact--in a political battle about to erupt again before the public over the future of a marsh land on the southern shores of the San Francisco Bay.

Last week, Bair Island activists took the dramatic step of placing a full-page ad in the West Coast edition of The New York Times, again bringing the dispute over the land to a boil and triggering a rash of local coverage on the evening news clips.

Slough of Differences

THE BAIR ISLAND dispute is actually a story of two men with vastly different views about the largest remaining unprotected marshland in the south San Francisco Bay. For 14 years Nobles has been the leading figure in preventing development on Bair Island, insisting that the land be turned into a wildlife refuge.

His opponent, 59-year-old Don Warren, is just as adamant that his company, Kumagai Gumi, which owns the property, be allowed to transform the marshlands into prime real estate potentially worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

Warren believes all this can be done without destroying the tidal marsh habitat. Besides, he insists, the "island" is not an island at all, but several marshy pieces of land separated by waterways, called sloughs, cut by the daily inflow and outflow of tides.

"By calling the whole thing Bair Island they [environmentalists] create this aura around it," said Warren, who points out that Kumagai, one of the world's biggest development firms, hopes to build on the two inner strips of land, leaving the outer island as a wildlife refuge.

Nobles, however, believes the marshlands must be unbroken to provide sufficient habitat for species flirting with extinction, including the California clapper rail, the least tern and the harbor seal. "The reason it is so valuable is that there is enough wild land that the habitat is not too impacted by development," Nobles said, adding that the sloughs separating the islands from the mainland keep them relatively free of urban predators like dogs, cats and raccoons. "Once you lose a part of it, you lose the value of the whole."

Mud Wrestling

THE FIGHT OVER Bair Island began in 1982, when Warren and then-owner of the land, Mobil Oil Estates Limited, won the Redwood City Council's approval to develop a city with 20,000 homes, complete with a shopping center and corporate offices, on Bair Island. Ralph Nobles, then working at the Lockheed laboratories in Palo Alto, hit the streets with a newly formed citizen group, Friends of Redwood City, and gathered enough signatures to force a citywide vote on the plan. In the end, Mobil's plan was defeated by a mere 42 votes out of over 17,900 votes cast. A Mobil-backed, pro-development group outspent Nobles' group $159,000 to $30,000.

But the struggle over Bair Island is an example of the environmentalists' axiom that no environmental battle is ever permanently won. Seven years after the referendum, at the peak of the real estate market, Mobil Oil sold its land holdings on the San Francisco Peninsula, including Bair Island, to the Tokyo-based developer Kumagai Gumi in 1989. Kumagai retained Don Warren to make its investment pay off. This year, Warren says he will propose a new development plan for Bair Island to the Redwood City Council.

Nobles, still head of Friends of Redwood City and now a San Mateo County planning commissioner, will be Kumagai's biggest obstacle.

"We hope we never have to have another referendum election," Nobles told the Palo Alto crowd. "But if we do, we'll be ready for them."

Warren, who lives in Los Gatos, is president of the Bay Planning Coalition, a group Nobles playfully refers to as "Pave the Bay." A short, gregarious man with a firm handshake and windproof, Jimmy Johnsonstyle hair, Warren came to the Bay Area from Vancouver in 1973 to develop Mobil's land on the Peninsula. Since then, to many of the 14,000 residents of Redwood Shores, a city Warren and Mobil built over the last 23 years adjacent to Bair Island, he has become known simply as "mayor."

Redwood Shores, a planned community of homes with waterfront views, surrounds an artificial lagoon between San Francisco and Silicon Valley. It includes a shopping center, a health club, the 390-room Hotel Sofitel and corporate headquarters for Oracle, Nikon, DHL and Oral-B. The Redwood City tax assessor says that each year Redwood Shores pumps about $3 million dollars in property and sales taxes into the Redwood City treasury--almost 10 percent of the city's annual budget.

It has been Warren's dream since he came to the United States to build a sister city on Bair Island, which lies just across a slough, to the south of Redwood Shores.

Soon after the 1982 referendum defeat, in a masterful public relations stroke during a quiet city council session, Warren changed the name of Bair Island's two inner sections to "South Shores."

In the newsletter he distributes to Redwood Shores residents (who are Redwood City voters), Warren explained in a recent column titled "Unraveling the Description of Bair Island."

"From time to time, people erroneously lump together Bair Island and South Shores as Bair Island (Inner, Middle and Outer)," Warren wrote. "We have never intended to build on Bair Island."

Warren says Kumagai's plan is to turn the outer island over to the wildlife refuge. He hopes this will bring all but the most vitriolic opponents of development to his side.

Christopher Gardner

Flight Path: Bair Island is home to egrets, harbor seals and endangered species like the California clapper rail.

Bair Facts

FROM THE Bayshore Freeway, Bair Island doesn't look like much. As one walks across the land bridge over the stagnant slough that separates it from the mainland, reddish salt crystals crunch underfoot. White plastic pipes drain excess water into dikes, leaving behind evaporating ponds and cracked earth. The dikes are maintained by Kumagai to keep the two inner islands from flooding with the tidal movements, making land more suitable for development. They also keep it free of endangered species--a developer's worst nightmare. During the rainy winters a green carpet covers the inner islands, which are frequented by people jogging, walking dogs and watching birds. In the summer, Bair Island turns barren.

As prime waterfront real estate, Bair Island could bring $55,000 an acre, Nobles said. As a tidal marsh, the land is real estate only to wildlife.

"The developers were so anxious to show that the land had no use, they put a camel out there in 1982," Nobles said. "People talk about sticking a little dynamite in the levees at high tide, but that's just talk."

Bair Island's relative solitude has made it home to about 60 harbor seals. Diane Kopec, a biologist working for Earth Island Institute, a conservation group founded by David Brower in 1986, conducted a study of Bair Island's harbor seals. The harbor seal is more accustomed to people than any other seal. But still, she said, they are defenseless and skittish on land. They look for haulouts on secluded banks of the bay to warm their skin--especially when they molt and grow new fur coats. When their haulouts become less secluded, harbor seals leave.

Kopec has watched harbor seals compete for fewer and fewer secluded haulouts around the bay. A once-popular haulout at Strawberry Spit in Richardson Bay, in the northern neck of the San Francisco Bay, emptied out after homes were built nearby and new residents started walking their dogs along the spit, causing the seals to abandon the area.

Kopec believes development of the two inner islands would have the same effect on Bair Island's seals. On a recent visit to Corkscrew, she saw two jet-skiers buzz by, sending the seals diving. The seals are not endangered, but they are protected by the 1972 Marine Mammal Act. "There's a $1,000 fine, but it's never enforced," Kopec said.

The California clapper rail, a little bird found only on the shores of the San Francisco Bay, evolved without building natural defenses against civilization's predators. A clumsy bird that cannot fly, it forages for insects in shoreline mud and lays its eggs on the ground, making it easy prey for humans, cats, dogs and foxes. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service has pinned the survival hopes of the 500 remaining clapper rails on Bair Island's 3,000 acres of protected open space.

The Tide Turns

FROM THE GROUND, Bair Island's landscape stretches almost to the horizon, with the occasional distant passing ship giving the only perspective on where the land ends and the bay begins. The best way to appreciate its scale is by air. An aerial photograph hangs alone on the wall above Don Warren's desk on the top floor of a black-glass office building at the foot of the San Mateo Bridge. Using the photograph of Bair Island as a prop, Warren explained that this year he will make his case to the people of Redwood City that Bair Island/South Shores should be developed.

"We've hired the best people in the nation to do this," said Warren, who declined to reveal more details. "This time, we will be out educating the taxpayers."

When Mobil brought Warren to the Bay Area, he started work on the development of Redwood Shores, a grid of roads bisected by a lagoon on the peninsula just above Bair Island on the aerial photograph. Since then, he has become an expert at charting the maze of laws, regulations and government agencies--city, county, state and federal--that must be navigated before the first shovel breaks ground. As a developer, he said, 60 percent to 70 percent of his job is "dealing with one or more levels of government."

Since Mobil's referendum defeat in 1982, Warren found more than enough to keep him busy building Redwood Shores. When environmental regulations prevented him from filling a marsh or moving a slough, Warren used land on Bair Island as "mitigation"--donating acreage on the outer island to the wildlife refuge to compensate for environmental damage at Redwood Shores.

Soon after it bought Bair Island in 1973, Mobil donated about half of the outer island--800 acres--to the state refuge. The other half Warren kept in the bank.

"The rules for mitigation keep changing," he said. "If we trade [all the land] away, we lose our poker chips."

Redwood Shores matured during the real estate boom of the late 1980s. Warren's land was extremely profitable for Mobil, even with Bair Island lying fallow. But, as Warren said, "In the real estate business, everything is for sale."

In 1989 Kumagai Gumi made Mobil an offer it couldn't refuse. It paid $180 million for the remaining 320 unsold acres in Redwood Shores. Big, empty Bair Island was thrown in as gravy.

Within a year of the sale, the market crashed. Real estate values plummeted 30 percent throughout California. Kumagai decided to postpone new investment in Bair Island.

"It was all we could do to keep from losing money," Warren said. "We focused on Redwood Shores."

It was during the recession that Warren earned his stripes as a developer. "Redwood Shores stuck with their plan through thick and thin," said Joel Patterson, director of the Redwood City planning department. "Usually developers are in it for the money. Don Warren takes quite a bit of pride in the development."

Warren's tenacity paid off. Instead of tract homes, he invested in waterways and a lagoon in the middle of the community. Soon homes with waterfront views were selling for $40,000 to $80,000 more than identical homes on the other side of the street.

"We took the land that was planned for housing and put water on it," Warren said. "At $1 million an acre, people said we were crazy, but we were crazy like a fox."

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

In a full-page New York Times ad, development opponents go to press with their case.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Made in Japan

BEFORE HE gets to build South Shores, Warren's first stop will be at the Redwood City Council, where he must again submit a plan. Pending council approval, Kumagai's next step will be to pay for the city's preparation of an environmental impact report. Then there will be a public comment period, revisions and modifications. If the plan is accepted, the city would have to change the zoning of Bair Island. Any such change would be a legislative act. Any legislative act can be subject to a referendum--and Nobles will surely force one.

If, despite the odds, Warren wins the vote, the lawsuits would begin.

"Any development on those lands would not be permitted by the federal Endangered Species and Clean Water Acts," Nobles said.

The scope of those laws are open to interpretation. Warren said the inner two islands don't have endangered species--the direct result of artificially keeping the islands dry and barren, said refuge manager Marge Kolar. If the islands were exposed to tidal action, she said, the picklegrass would come back along with the clapper rail and least tern.

Court decisions could hinge on whether all three islands are historic wetlands, or whether the land is deemed an "important and necessary" habitat for endangered species. If the inner two islands don't pass this test, the decision would hinge on whether development there would adversely affect animals on the outer island.

For his part, Nobles wants the voters to decide and not the courts. Friends of Redwood City plan to distribute at least 15,000 videos titled "Bair Island Wetlands" to households throughout Redwood City, which has 71,000 residents.

And, to try to convince Kumagai to cut its losses, Nobles reached far over Warren's head to the president of the company, Taichiro Kumagai, who is based in Tokyo. He sent a letter to Kumagai to express both the environmentalists' will and their willingness to fight.

But corporate Japan is secretive and hierarchical. Kumagai is, as real estate industry analyst John Wade put it, "a black box--you know the name on the outside, but have no way of knowing their business plans."

Wade is director of land protection for Peninsula Open Space Trust, a private organization that buys land to be preserved as open space. Wade, who has acquired thousands of acres on the Peninsula, has been eyeing Bair Island since he moved to Redwood City in the late '70s. He was involved with Nobles in the 1982 referendum on Bair Island and has explored its winding sloughs by canoe.

Wade estimates that Kumagai, one of the largest privately held corporations in the world, is worth $8 billion with 8,000 employees.

Sitting outside the office of the trust off Sand Hill Road in Menlo Park, Wade said Kumagai's motives are difficult to discern.

"Kumagai bought the land at the peak of the market," he said. "The dollar has also gone down against the yen."

Before Kumagai discovered Bair Island's history, Wade said the deal to buy Redwood Shores and Bair Island from Mobil could have gone as high as $400 million. But even at $180 million, Wade believes Kumagai must have been gambling that Bair Island would one day pay off.

According to Wade, Kumagai would have to make close to $270 million from the remaining 320 acres just to break even on the deal, factoring in inflation, construction costs and debt service--further proof that the company is counting on cashing in on Bair Island.

"They maxed out on the easily developable stuff in Redwood Shores," Wade said. "Now all they have is Bair Island. They just misjudged the market."

Despite Kumagai's size, there is some evidence that questionable land speculation in the U.S. has hurt the company.

"[Kumagai] has been crippled by disastrous real estate investments in New York, California and abroad," reported the Puget Sound Business Journal on Oct. 14, 1994. Kumagai also has an appetite for created real estate. In Hong Kong, Kumagai is a major contractor in the construction of a new airport to be built on a man-made island.

Wade said that cultural misunderstanding can make dealing with Japanese corporations difficult. Environmental protection and the idea of "wetlands" as an ecosystem are foreign concepts on an island nation where man has historically contested with the sea for scarce land.

"In Japan they don't give a damn about wetlands," Wade said. "As far as I know, except for Mount Fuji, the idea of protecting wild land is an afterthought at best."

Last year, the federal government tried to buy Bair Island. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service made a formal offer to Warren for all three sections of Bair Island that would have added it to the San Francisco Bay National Wildlife Refuge. Expansion of the refuge was authorized by the Reagan administration in the 1980s, but no money was ever earmarked to pay for it.

"Their offer was serious, but untenable," said Warren, who noted that the government's offer was only 15 percent of the value of the property. "They wanted it all," he said, sweeping his index finger across the width of the photograph above his desk. "They wanted to put up a chain-link fence to keep people out."

According to Wade, Kumagai's property is worth about $10 million. But even if Kumagai asked a "laughable" $50 million, Wade said it still might be possible for the public to buy Bair Island and turn it over to the wildlife refuge.

Last year, Congress gave Warren some reason for optimism on two fronts. Conservatives in Congress, who believe the federal government has no business owning land for public use, are working to scale back laws that hamstring private land developers.

After they took the House, Republican representatives wasted no time passing a tenet of the Contract for America called the Job Creation and Wage Enhancement Act, which would force the federal government to pay "fair market value" to landowners if environmental regulations decreased the commercial value of their land by 50 percent or more. As a senator, Bob Dole sponsored a bill called the "Omnibus Property Rights Act of 1995," which would force compensation if land values were reduced by 33 percent or more.

Tara Mueller, an attorney for the Natural Heritage Institute in San Francisco, says it is unlikely Dole's bill will be considered before the elections. "Environmental issues are replacing Social Security as the 'third rail' of politics," Mueller said. "Touch it and you die."

But relaxing environmental regulations may not, on the whole, increase the value of wetlands as real estate.

"If they do deregulate wetlands, it might not change the value of the land because it would throw hundreds of thousands of acres on the market at once," Wade said. "Fools build on wetlands. They'll get flooded out in 10 years and want government assistance."

The irony of the situation, Wade said, is that the same interests that so desperately want government to relax regulations would put themselves in a position where they may need government help.

"A lot of speculators want the government to guarantee the value of their holdings," Wade said. "The speculators blame their woes on government."

Man vs. Man

MARSHES, SWAMPS and shorelines--both salt- and fresh-water--can all be described under the broad term "wetlands." In the 1960s, many environmentalists realized that areas where water regularly ran over land were vital natural habitat. San Francisco Bay wetlands have distinctive plant and animal life and are a vital bottom ring of the food chain. They filter impurities and silt, and act as a sponge that prevents flooding.

The wetland ecosystem is surpassed only by the coral reef in generating life. A double handful of mud may contain a many as 40,000 tiny living creatures. At one time, the San Francisco Bay held the largest such inter-tidal habitat on earth. But the bay is one-third smaller than it was before wetlands were filled to create dry land. San Francisco's financial district stands where the bay once lapped the shore of the Peninsula. The San Francisco Estuary Institute in Richmond, which conducted the most ambitious survey of historic wetlands in the bay, reports that only 10 percent of the original 195,000 acres of wetlands remain today.

Before the sea walls, airports, highways and parking lots--before San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose and everything in between--an expansive green carpet lined the San Francisco Bay. Ohlone Indians paddled sloughs, fishing the same tidal waters as grizzly bears, harbor seals and snowy egrets. Turning the land back to its past, not just creating piecemeal sanctuaries for wildlife, has been the goal of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Bair Island since the 1980s. The beauty of Bair Island, Nobles says, is that it would be so inexpensive to restore it--simply knock down the levees and let nature take its course.

But human commercial enterprise also has been a part of Bair Island for the last 100 years. Around the turn of the century, an oyster-processing plant prepared mollusks for export at Corkscrew Slough. Redwood City's long-disappeared giant redwoods were cut and shipped past Bair Island from the port of Redwood City. In the 1920s, the island's namesake, Fred Bair, owned a house on the outer island, where he harvested oysters and raised cattle. And from the 1940s to 1973, Bair Island was diked into salt-evaporation ponds by Leslie Salt, which owned expansive tracts of ponds that ringed south San Francisco Bay.

To Don Warren, there is no reason for the human use of Bair Island to cease.

"We knew about the sensitivity of the land, and that the traditional land development approach wouldn't work," said Warren, who frames his plan as a sensible compromise between environmental and commercial interests.

For both Nobles and Warren, the 1982 referendum was a defining experience. Nobles overcame opposition in the city council, on editorial boards of local newspapers and from a community that was largely unaware of the valuable bay ecosystem where land meets water. But in the end, it was Warren who found that good finances and political support are not enough to start a new development on the San Francisco Peninsula.

For Nobles, Bair Island is a fascinating venue for studying the wetland environment. But his are not the rantings of a tree-hugger. Nobles' background is that of a nuclear scientist, not an activist.

Expecting to be drafted as a 19-year-old high school student in Missouri in the early 1940s, Nobles applied to the Manhattan Project at the suggestion of his physics teacher. On July 16, 1945, 200 miles south of Los Alamos, N.M., Nobles became the youngest person to watch Trinity, the world's first atomic bomb, as it lighted up the desert as intensely as the midday sun. Thunder from the blast echoed for minutes against the mountains, and an ominous purple cloud stretched toward the heavens.

After the detonation, prevailing winds blew radioactive fallout in the direction of Nobles and the other researchers watching from an observation tower six miles from ground zero. When Geiger counters began to detect a radioactive cloud blowing in their direction, they made their escape.

"We couldn't outrun it--we had to avoid it," Nobles said. Their convoy sped across the desert at a right angle to the direction of the wind.

That was the last time Nobles worked on the bomb.

Nobles worked well into his 70s as a full-time nuclear physicist at the Lockheed laboratories in the Stanford Industrial Park in Palo Alto. For many years, he also owned a small sailboat that he docked in Redwood City. He said that being a sailor gave him a new perspective of the waterfront.

He had seen the wildlife on Bair Island and began to think that in sprawling Redwood City, filled with cars, roads and parking lots, development did not necessarily mean progress. To Nobles, continued urban expansion defies both science and logic.

"It just seemed so wrong," he said. "I don't think any of us wants to live in a completely unnatural world."

Despite their long feud, Warren and Nobles have a surprisingly genteel and respectful personal relationship.

"Warren is a very effective man," Nobles said. "He has a lot of history and acquaintances in Redwood City."

Recently, Nobles and Warren ran into one another at Kumagai's offices and spent an hour chatting. According to Nobles, Warren said, "I've even mellowed in my old age and joined that 'Save the Bay' organization."

In the waiting room outside Warren's office, the walls are adorned by black-and-white photographs of classic California nature scenes: Yosemite's Half Dome, the snowy banks of the Merced River, waves crashing on rock formations and a coastal scene lined with redwoods.

Redwood Shores has been internationally recognized as a gleaming specimen of the "new towns" movement, Warren explained proudly. Revived in the late 1950s, "new towns" were intended to be self-sufficient suburban communities at a time when developers unconsciously built mushrooming rings of suburbia around cities in the postwar period.

"Rather than let urban sprawl spread like topsy, we decided to build new cities," Warren said.

Neighboring Foster City, the Southern California city of Irvine and the East Coast developments of Columbia, Md., and Reston, Va., are all examples of the movement that tried to incorporate homes, shopping, schools and offices in the same community.

In Warren's office, oar blades mounted on wooden stands and painted in the colors of Stanford, Cal and other PAC-10 schools are displayed prominently. Warren designed the lagoon that runs through Redwood Shores as a 200-meter course for rowing competitions. Stanford uses the lagoon for regattas.

Warren's fascination with the sport began in 1954, when he became friends with members of the university crew team at the University of British Columbia. That year, the team won an Olympic gold medal.

As a businessman, Warren sponsors intercollegiate regattas and explains a profound admiration for the athletes who participate in a sport that requires such endurance, discipline, tolerance for pain and willingness to sacrifice for the team.

"I've never rowed myself," he said. But if he were hiring a college graduate, he said he would consider participation in the sport as important a qualification as grades, test scores or experience. For Warren, tenacity of this kind is the key to success.

"It will be a difficult process," he said of the task ahead on Bair Island. "We were told we would never be able to develop Redwood Shores."

Warren has worked over 20 years to develop Bair Island/South Shores into what he sees as another suburban utopia. Years of studies, permits, lawsuits and perhaps even public opinion stand in his way. But despite those odds, this year he will fight to build a second city on the San Francisco peninsula. Ralph Nobles will be ready.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)