Christopher Gardner

Where There's Smoke: Neighbors worry that Kaiser Cement's test burn of old tires at its Cupertino foothills facility increased dioxin emissions 54 percent.

Kaiser Cement insists the air pollution caused by burning old tires instead of coal is minute, but can Santa Clara Valley's air take the toxic hit?

For 45 days last winter, unbeknownst to the general population, the Kaiser cement plant in the hills above Cupertino burned 100,000 Michelins, Goodyears and Pirellis. Management at the 57-year-old plant was conducting an experiment to see if it could substitute scrap tires for a portion of the Utah coal that normally fires its kilns.

The Bay Area Air Quality Management District, which declared 25 Spare the Air days the same year, had quietly issued Kaiser its experimental permit in November 1995. And Kaiser was anxious to prove that burning tires--a vastly less expensive energy source than coal--would have no "significant" environmental impact, paving the way for a permit to burn tires full-time.

"We have 3,000 pages of test results," says Earl F. Bouse Jr., a vice president of Kaiser Cement. "The next step is for us to put in an application to use [tires]."

The results, compiled by Radian International, the consulting firm Kaiser hired to interpret the test data, showed increases during the test in benzene, dioxin, polyaromatic hydrocarbons, airborne particles, hexavalent chromium, copper, lead, manganese, mercury and zinc emitted from the plant. Most of the increases were slight, and some of the chemical emissions normally associated with coal actually decreased during the test.

Despite the increases, all the emissions during the test were well below state standards. But a group of Cupertino residents, and the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition, have served notice to Kaiser that any increase in pollutants from the plant, no matter how slight, is too much for the valley's already abysmal air to absorb. They hope to force Kaiser to conduct a full environmental impact report, in addition to the $250,000 study conducted by a private firm, before one more retread is tossed into the kiln.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Pollution settles in the valley, making air quality in San Jose worse than the Bay Area average.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

KAISER'S DREAM of using scrap tires in its kilns reflects a major trend in the cement industry. Thirty-three other plants in the United States now burn some percentage of tires as fuel. Kaiser says that substituting scrap tires for 10 percent of the coal it normally uses will save the company about $500,000 every year. And what else is the country going to do with all its old tires, anyway?

Beyond the cement companies, the tire-burning trend makes municipal waste managers and the tire industry very happy. Americans annually discard a tire per every man, woman and child--over 30 million per year in California alone. This presents an ongoing waste-management migraine for local governments. It also looks bad for the tire industry, whose products are subject to increasing taxes to help pay for the disposal problem.

This triumvirate of tire-burning boosters wage constant battle against the image of burning tires most people have in their minds. Combusting tires under controlled conditions in sealed cement kilns, they argue, is as safe, if not safer, than burning coal.

"Tires are benign, they are not a hazardous waste," said Michael Blumenthal, director of the Scrap Tire Management Council, a lobby funded by the tire industry. Blumenthal was hired to head the organization in 1990 to promote "viable markets" for scrap tires.

The vulcanization process discovered by Charles Goodyear that makes tires indestructible is also virtually irreversible. In other words, they can't be melted into material for new tires. Last year 131 million scrap tires were burned as fuel in cement, power and paper plants. By comparison, 12 million were used for civil engineering in road embankments, landfill and highway barriers. Six million were ground into particles to make rubberized asphalt, hoses, mats and playground material. More than 30 percent of the tires scrapped last year were tossed into landfills.

Proponents of tire burning argue the cement-making process is especially suited to disposing of tires. The process that slowly super-heats limestone combusts the tire completely, steel belts and all. Any ash or oxidized metals become part of the product.

Imagine, an old tire that just vanishes! Could this be the tire collecting water and mosquitoes by the railroad tracks, the one stuck in the mud on the banks of a slough? Or one of the estimated 500,000 currently piling into mountains in the Santa Clara Valley? Blumenthal says the answer is yes.

BUT TIRE BURNING has not been welcomed with open arms everywhere. Some environmentalists say the practice benefits industry more than the environment. RMC Lonestar, a cement plant in Davenport, near Santa Cruz, gave up its plan to burn scrap tires three years ago in the face of citizen and local government opposition. Tire burning at California Portland Cement near Mojave was stopped when a judge withdrew the company's permit until an environmental impact report was conducted.

Leslie Byster of the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition argues that the quality of the ambient air in Santa Clara County is already poor. Measured in health risk per million, downtown San Jose scores 500 while the rest of the Bay Area averages about 300. According to estimates released by Austin-based Radian, an environmental contractor for government and industry, Kaiser's emissions contribute a total health risk of 4.6. Burning tires would only increase that to 4.8. But Kaiser's emissions alone already constitute almost 1 percent of Santa Clara's total health risk.

"These plants are high pollution sources," says William Pease, research toxicologist at the University of California at Berkeley. Pease conducted a study of cement plants that burn tires, and found the difference between coal and tires to be very small. "We didn't find that using tires made a drastic change in the type of pollutants released. I doubt you would find anyone in the scientific community who would say otherwise."

But some of the activists opposing Kaiser say any increase is too much.

"All polluters can say that they are only adding a little bit," says Byster. "Even if they're right, this is preventable pollution."

EARL BOUSE and his community relations manager, Ralph Venturino, were waiting for me when I arrived at the Kaiser plant at the end of Stevens Creek Boulevard. Spread across the conference table were three-foot-thick volumes of study results and the previous week's Metro, open to the cover story about the specter of corporate sponsorship of national parks. Bouse seemed particularly tickled by the illustration.

"I see you've got a corporate guy pissing on the environment," he said.

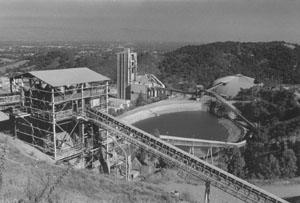

Kaiser has been chipping limestone out of the hills above Cupertino since it was built by American industrialist Henry J. Kaiser in 1939. The plant's first task was to crank out the 1.1 million tons of cement needed to build the Shasta Dam across the Sacramento River.

The chain of Kaiser hospitals evolved from the health plan Kaiser provided his cement workers. The modern-day HMO and the cement plant are no longer connected.

Our tour began at the massive dome where freshly mined and crushed limestone arrives by conveyor belt to be sorted. The limestone is dumped in a circular pile and a sample taken to determine its purity.

Then the limestone leaves the dome on a conveyor that takes it to the first of two furnaces that super-heat the stones to 2,800 degrees Farenheit. The whole burning concoction of limestone, coal and--if Kaiser has its way--tires is then poured down a revolving cylindrical kiln. The cooled product is called klinker, a hard, black substance that is ground up and mixed with gypsum. That's cement, the substance that glues rocks together to make the concrete in roads, bridges and subway stations.

Emissions are sucked into the "bag house" and filtered. Thirty-six stacks discharge an odorless exhaust that is invisible from the west, but a faint blue-gray from the east.

Bouse has worked in the cement industry since he came to the Bay Area from Montana in the 1960s. Some of his efforts to help Kaiser be a good neighbor to Cupertino include an electronic sign that posts the speeds of truckers on Stevens Creek, and a $100,000 vacuum truck to fight the dust.

Bouse has a folksy manner about him, openly admitting he has to wash his car every few weeks, or the ubiquitous dust may turn to cement in the first fog bank.

But his chance to have an amicable relationship with many people in Cupertino may have been lost last November, when residents learned of the tire burning not from Kaiser but from Sue Abby of the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition.

RUTH SCOTT REMEMBERS the Sunday that Sue Abby came to her door. She was spending time with her father, while her two sons worked in the back yard. The activist informed Scott the experiment would take place over the next few months, and it filled Scott with dread. Her younger son, born with a weak immune system, takes antibiotics regularly to stay healthy enough for school.

"Our son started getting sick when we moved up here three years ago," recalls Scott. "My husband said the other night maybe we should move, find some place where the air is safer." She has made plans to fork over the $800 it will cost to test him for sensitivity to dioxin.

Leslie Fowler lives within earshot of the Kaiser plant. During the test dates, she says, she wiped excessive dark-colored dust from the screens in her house. Fowler says that had she known about the plant four years ago when they were buying a house, they might have looked elsewhere.

THE BURNING ISSUE of tires appears to be adding fuel to the already hot race for the Santa Clara County Board of Supervisors between Barbara Koppel and Joe Simitian. Koppel, a Republican and former mayor of Cupertino, worked for Kaiser part-time 13 years ago. She also received donations from Kaiser employees when she sat on the board of the Bay Area Air Quality Management District. When Simitian accused her of a conflict of interest, Koppel argued that all decisions on Kaiser's permits were made by the air district staff, not the board members. Koppel also accepted campaign checks from Kaiser Cement, as well as Kaiser Sand and Gravel. Since both companies are owned by Hanson Industries, a British conglomerate, Koppel violated campaign finance rules by accepting more than the legal limit of $350 from one company. Upon discovering the violation, Koppel returned $350 and said the checks had come from different addresses and different banks.

Despite her Kaiser connections, Koppel has sided with the neighbors in asking for an environmental impact report.

Simitian also says if elected he will push for a "rigorous" environmental impact report on Kaiser's plans, performed by the county.

THE ENVIRONMENTAL Protection Agency recognizes dioxin as the most carcinogenic synthetic chemical known. It increased 54 percent during Kaiser's test. But no matter how small Kaiser says the increases were, it is too much for the Silicon Valley Toxics Coalition and the West Valley Citizen's Air Watch.

Their point is that Kaiser's emissions are already high, and this is where they want to draw a line in the sand. Forcing Kaiser to undergo an environmental impact report would balloon its costs. It could also effectively halt Kaiser's tire-burning plans for years to come.

A exasperated Bouse is candid at the prospect of more study.

"We're in the business of making cement," he said. "If it's something that's going to be a drag-out fight for four or five years, why do it?"

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)