Art to the Max

From 'Yellow Submarine' to the sides of buses, Peter Max's designs defined the sixties

FEW ARTISTS are as evocative of a time and a place as Peter Max, and though the time ran out and the place vanished, the artist still remains. Max, who will appear Friday (Oct. 23) at the Virtual Gallery in Los Gatos, was the great celebrity artist of the 1960s and the foremost representative to the mainstream of the psychedelic style.

Max was more easily recognizable and more accessible to the public eye than Andy Warhol. The characters in the Beatles movie cartoon Yellow Submarine were blotchy copies of Max's originals. His designs were everywhere, from the sides of busses to inflatable vinyl pillows.

Max had sold 2.5 million posters by 1969. His vibrant colors and clean, cartoonish lines were wildly popular. Each design bore his bold trademark: his name in an oval cartouche, written in sloping Art Nouveau calligraphy. Max's heyday as a celebrity artist was described in June 1968 in a burst of typically breathless Time magazine prose: "He zaps around Manhattan with his blond beret-crowned wife in a decal-covered 1952 Rolls Royce with a liveried chauffeur." (By describing Max as colorful kook, Time obscured an important first: Max tells me that the decals were made specifically from his drawings; for what it's worth, then, Max drove one of the first art-cars.)

Today, you reach Peter Max through a lattice of receptionists; and you have lots of time to think about your sins listening to pretty on-hold music with flutes in it. The man himself, 60 this year, still nails down a busy schedule. He apologizes for the lateness of a callback, on the grounds that he'd been on the QVC Channel until 1:30am the previous night. "To our happy surprise," he says, "we sold 2,000 signed posters. I think we made half a million yesterday."

I wondered if he didn't get carpal tunnel from signing all those posters. "Nah," he replies, "I do about one or two hundred and then take a break--and then sign some more."

Max didn't realize that he was speaking to an ex-12-year-old who owned a prized Peter Max notebook. Thus the artist explained that he had once upon a time made millions in retailing. "I had licensing agreements in 1970 with Van Heusen, J.P. Steven, all the biggest corporations--I'm starting up all of the franchising all over again." Max seemed especially chipper since he'd just recently handled some tax-evasion problems with the IRS. "All that is settled now," he explains. "I didn't have to go to jail, thank God. I had a bad manager is how that happened."

WHEN YOU ARRIVE in America from Canada, see that sign that says "Welcome to the United States?" It's a Max design, spangled with his trademark cartoon stars; it is fancifulness incarnate, politically correct because it's politically neutral. The signs promise that you're entering a fantasyland where any berserk thing can happen. Can't call that false advertising--and the signs were created by an immigrant.

Max grew up in the milieu later immortalized by novelist J.G. Ballard in Empire of the Sun. He was the only child of a German-Jewish couple that had relocated to Shanghai to escape the fury of the Reich. In Shanghai, his father ran a small import/export business. Like Ballard, young Max was tended by a Chinese nanny (an amah to crossword-puzzle lovers).

She and the others in the neighborhood wrote their Chinese characters with sumi brushes, and these brushes were Max's first drawing tools as a child. After the war, Max lived in Israel, India, Africa. When he came to New York as an art student, he studied realism at the Art Students League.

"My teacher there, Frank J. Reilly, was a co-student with Normal Rockwell, both of them learning under Dean Corwell, a famous muralist," Max recalls. "I studied figure drawing for seven years, life drawing from nude models, learning body and fabric, light and shadow."

Although Max has been experimenting with computers for creating his art lately, he still uses his easel. "I'm a real painter," he says. "I really enjoy the creativity at the easel, with the real brushes and pigment, paint and textures. Some computer artists bypass paints, but they're limited to the thin computer line. And there's a thousand times more free flow in the hand and the wrist and the elbow with a brush."

When Max emerged from art school, he was dismayed to see that photography had taken over: "Avedon, Scavullo, Irving Penn and guys like that could knock off 40 images in no time at all. I realized that it was ridiculous to paint realistically." At this point, Max changed his style from technical accuracy to more intuitive painting: "China burst through my chest," Max says, dramatically. "That's when I started my work."

Max's art was influenced by a favorite artistic period, the 1890s. This was the era of the Fauvists, or "Wild Beasts," the artists who used brutal color contrasts. At the turn of the century, Art Nouveau entered commercial art, with its tendencies to adapt the shapes of vines and vegetation to iron ornaments. (Many of the Parisian Metro stations still standing are executed in this style, their entrances framed with cast-iron leaves and lilies.)

The women in Max's work recall the voluptuous cigarette-paper advertising posters of Alphonse Mucha. The British illustrator Aubrey Beardsley is also important to an artist who once loved drawing lean, long-legged imps, with huge perukes of hair on their heads.

Repressive times--whether it was WWII or the Nixon regime--looked back in nostalgia to the peace, opulence and easy morals of the 1890s, and Max struck a nerve. "I got about 250 design awards a year," he says. "I did posters for fragrances, covers for TV Guide and U.S. News and World Report, soup to nuts. That's when I learned that brand building was very important, and that's when I began putting my logo up there. Eventually, companies hired me just to get the logo up there."

The amount of work Max and his studio generated must have given him a rather more hard-working '60s than most who were there. He doesn't feel like he missed anything.

"I just was in glee bringing that generation into the limelight," Max says. "It was so fabulous, so rich in its aura, in its hopefulness. It was the first time man saw planet Earth taken from afar, photographed from above. It was evident there are no borders, this is one big park, all the divisions aren't important."

That optimism seems a long time past, in an age of scarcity and nationalism. "It's going to be a long process, " Max says. One part of the spirit of the '60s that remains important to Max is the importance of Eastern religion.

Max was an early patron of Swami Satchidananda. "I begged him to come to America, telling him, 'America needs you.' America was experimenting with drugs, and they'd get the feeling of inner peace and inner silence, but you couldn't keep the feeling for more than a night. Satchidananda spent 10 days with me and my wife, then he started an ashram at the Oliver Cromwell Hotel. He has 39 ashrams today, including. Of all of the things I ever did, maybe this was the most important, even the most patriotic."

ABOUT 30 YEARS AGO, Business Week started out an article on Max with the cliché "There's a thin line between art and commerce." Max's success has been due to not seeing that line at all. In a time when hippies fretted about selling out, Max was designing household clocks made by that stalwart of the nuclear industry, General Electric.

Later, Max created official art for all the presidents, including Reagan. You may not think of Ronald Reagan as a Peter Max fancier, but Max claims, "They all are, all of the presidents. I'm a yogi, I practice yoga, and I'm always in that frame of mind. So I believe in supporting the president and support the country as it is. So I was behind Carter, Reagan, Bush, Clinton. I just saw Clinton a few days ago. The first time we met, he said that he and Hilary had my posters all over their walls when they were young."

While honoring his business acumen, the major news magazines used to needle Max. What their articles suggested was that underneath every hippy was a hip capitalist. Describing Max as a "millionaire hippie" was a way of targeting the flaws in the youth movement, implying that every one was waiting to sell out their high-toned values if they just got a big enough check.

But Max was so completely free of political agenda, it's impossible to describe him as even bearing an agenda, other than the Artist's Imperative: to draw pictures and not to starve doing it. Max's art is inimitable. No, actually, it's easily imitated, but it's extremely obvious where it's being imitated. So Max's invention of the brand name as art--seen today in the jumbo CK logo on a Calvin Klein sweatshirt, and many other places--may be his greatest artistic achievement.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

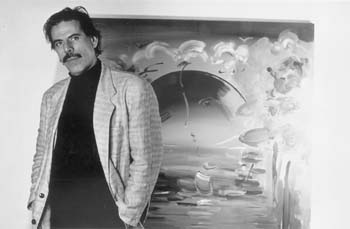

Rick Bard

The Peter Principle: Although he has been using a computer for some of his work, Max still prefers the feel of a brush.

Peter Max appears Friday (Oct. 23), 6-10pm at the Virtual Gallery, 105 N. Santa Cruz Ave., Los Gatos. The show previews Oct. 22. RSVP at 408/399-3456

From the October 22-28, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)