![[Metroactive Stage]](/stage/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

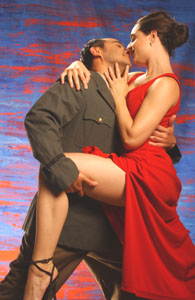

Dance of Danger: Emily Duarte-Rosenthal and Jaime Avelar-Guzmán carry on an affair amid the political turmoil of Pinochet's reign in 'Chilean Holiday.' The Other 9/11 Teatro Visión finds humor in the tragedy of Chile's dark days under Pinochet in 'Chilean Holiday' By Marianne Messina AFTER A WEEK of news reports about police shooting at peasants from helicopters and overpasses in El Alto Bolivia, it was appropriate to go to the Mexican Heritage Plaza to see Chilean Holiday. Billed as serio-comedy, Guillermo Reyes' festive title actually refers to the holiday imposed on Chile by Augusto Pinochet to honor the day of his bloody coup--Tuesday, Sept. 11, 1973. "They are still with us, the enemy," Pinochet's voice announces over the radio at the play's beginning, "they are everywhere, these terrorists." And at that point, I considered the theatrical truism that in times of social stress, people don't need to be reminded of their troubles at the theater. But Reyes' play isn't about reminding, it's about taking an insightful look at the tragicomic human hatchery beneath these troubles. In Chilean Holiday, Digna and her suitor, the police officer Lautaro, are both passionate and conflicted. Emily Duarte-Rosenthal gives Digna breadth, as an impetuous, opinionated "princess" with just a touch of unmarried-at-30 vulnerability. Jaime Avelar-Guzmán generates a strong-silent mystique with ease as Lautaro, though he somewhat lacks the smooth charisma of the Olympic-bound equestrian hero and self-proclaimed Don Juan--or Don Quixote, as Digna corrects him. But as Chile's "disappeared" start turning up dead in mass graves, and it becomes impossible to deny the handiwork of Pinochet's soldiers and secret police (DINA), Digna and Lautaro are forced to get their internal houses in order. For Reyes' characters, fitting into a dictatorship means distilling inner tensions down to some core essential. Enter Yolanda Cotterall, a dynamo full of nuance as Lautaro's mother, the feisty bartender Doña Conchita. Not only does Doña Conchita embody the wonder of contradictions that make up a human being, but she's a quick brush stroke of Reyes' genius for the humor in tragedy. "Don't use that tone," she says to Lautaro. "We're your elders. Even if we are all drunks." In Conchita, we see how a dictatorial regime can gain purchase. She has long been against the Communists and in favor of a strict government, "a necessary evil to keep you young kids in line" (the same kids to whom she sells alcohol). But in Conchita, we also see how good-hearted people can get crushed in a runaway machine. "Why can't we have just a regular old dictatorship," she laments, "not the secret police?" In the moving moments when Lautaro announces that he's been selected to join the DINA, Doña Conchita decides that her rancor was just talk uttered under the influence. And similarly, the other characters must decide which parts of themselves to cut off, which to espouse. Age group or romantic connections? Compassion or indignation? Roots or way of life? Career or beliefs? "How am I supposed to get to the Olympics?" Lautaro cries out. And he answers himself, "You play the game." Reyes' tough, funny play shows that while his characters have hard choices--ones that may decide who informs on a neighbor, becomes a martyr, joins a resistance movement--they are choices everyone is free to make. Director Pamela Salazar-Schell and Teatro Visión deserve kudos for a well-done, heady production that provides illumination of, not escape from, the difficult truths.

Chilean Holiday, a Teatro Visión production, plays Oct. 23-25 at 8pm and Oct. 26 at 2pm at the Mexican heritage Plaza, 1700 Alum Rock Ave., San Jose. Tickets are $12/$17. (408.928.5585)

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the October 23-29, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.