![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

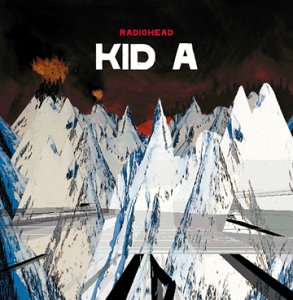

Sex, Dread and Rock & Roll On 'Kid A,' Radiohead embraces the anguish of rock By Gina Arnold RECENTLY, the U.S. Court of Appeals heard the RIAA's case against Napster, and (as had been the case at the previous hearing, only more so) the San Francisco courtroom was packed with media representatives from around the world. Most of the reporters were tech or business types, so it was downright astonishing that one of them, upon learning of my specialty, asked eagerly if I'd heard the new Radiohead record yet. It was the only mention of actual music during the proceedings (minus lawyer David Boeis' example of why a search eliminating, say, the song "Age of Aquarius" (his choice) couldn't reasonably be implemented. Not surprisingly, the reporter who inquired about Radiohead was from England--the band's country of origin and a place where it has reached superstar proportions similar to those of R.E.M. five years ago. In 1998, readers of Q magazine--the English equivalent of Rolling Stone--voted the band's 1998 record, OK Computer, the Most Important Record of All Time, an indication of Radiohead's stature in England, if not of its sales. In England, if not here, Radiohead is regarded as the band whose music matters the most right now. Radiohead is the harbinger of all things pop-cultural. This is a surprising development, given the group's banal beginnings, its one hit (the 1992 song "Creep") and its depressingly old-fashioned attitude. Radiohead plays prog rock, pure and simple, and prog rock with a single theme: the deadening effect of modern life. Nevertheless, like Oasis, the Smiths, R.E.M. and the Velvet Underground before it, Radiohead now inspires other bands to fits of emulation. Indeed, Travis--last year's Next Big Thing in England--is pretty much a Radiohead wannabe whose record neatly filled in while Radiohead was still recuperating from the giant success of OK Computer. Travis plays Pearl Jam to Radiohead's Nirvana, and just as Nirvana's post-Nevermind album was scrutinized for cultural signposts, Radiohead's Kid A (Capitol Records), its first LP in three years, is being carefully studied (like worm sign in Dune) for some indications of the direction of Rock Itself. There's plenty to talk about, too, since the record not only represents a radical departure from previous work but is also being plopped into the middle of one of the most unpropitious musical landscapes ever. Kid A is, in fact, Radiohead's fourth LP. Early word mentioned the fact that it was "ambient," but that's putting it mildly. The NME--a British paper that takes everything Radiohead leader Thom Yorke says very seriously indeed--wrote that the album exhibited "a mood of breakdown and psychosis," and you can say that again (which is why I just did). Kid A is full of loops and sound effects, pulsing and repetitive beats and disembodied vocals--mainly Yorke cooing and yelping short, distressed phrases that have been put through a voice processor. The words "is this really happening?" and "this isn't happening" appear in several songs; elsewhere, the lyrics indicate a level of desperation: "I am crazy maybe," "women and children first," "flies buzzing round my head" and "I laugh until my head comes off." The whole record is built up on layers of rhythm tracks--and yet it is practically impossible to dance to, thanks mostly to Yorke's horrid world view and distinctly anguished and alienating presence. Not only is it undanceable, but the CD is 50 minutes long and all but tuneless in the conventional sense. Only the songs "Optimistic" (my favorite), "Everything in Its Right Place" and, possibly, "Idioteque" demonstrate a modicum of melody--but "modicum" is the operative word. If you attempted to download a song like "National Anthem" or "Treefingers" from Napster, you might think at first that you'd accidentally captured the modem noise by accident instead. The funny thing is, all these things together ought to make Kid A one of the most unlistenable records ever. But it's not (although fans of the band's more singable work should approach this record with caution). Kid A makes for compelling, even at times enjoyable, listening, and here's why: The thing that Radiohead possesses that other bands lack these days is integrity. The most obvious form this integrity has taken is the fact that Radiohead insisted on touring this summer in tents that lacked all sponsorship logos. Its less obvious form is more subtle. Radiohead's members aren't nice-looking, and their songs are not anthemlike or catchy, but they have the courage to show the world their vision of rock, in all its ugliness, without flinching from the resulting anomie and chaos. After all, truth is beauty, beauty truth--which may explain why Kid A is actually quite beautiful, despite all those limitations. What I like about Radiohead is its ability to transmit its feelings whole. Without even being a big fan, I really feel like I "get" Yorke's vision; I know what's on his mind. Part of this feeling comes from having seen the group live. I was unenamored of OK Computer, but Radiohead's live show was much more absorbing than I had imagined--purer, more intense. Also, the band's beautifully shot concert movie, Meeting People Is Easy, did a lot to explain its central theme for me. In Meeting People Is Easy, the band members moved like automatons through the boring and alienating tasks associated with a world tour. Thus, they are captured in stilted interviews with dumb reporters, sitting alone in lonely hotel rooms and, most hauntingly, performing onstage in dark arenas in front of the faceless, invisible hordes of fans. (The song "How to Keep From Disappearing" on Kid A reflects this experience.) Kid A transmits the severe disjunction such experiences cause, and there is something touching about that. The album's numbers--they're not songs--seem intent on killing the thing the band (presumably) loves most: that is, rock, with all its pomp and purpose. After all, if you take away the melodies and words and funky beats of rock, what do you have left? Only emotion, and the emotion conveyed here, in one beautiful and easy to understand swoop, is dread. Can it be possible that Radiohead dreads the very thing it makes, and that is what makes it successful? Judging by Kid A, yes--but dread is definitely a healthy thing, especially in times like these, when rock & roll is all but over, corrupted and rotten and silly. Kudos to Radiohead for not feeding on its corpse, but showing it to us--and helping us mourn properly. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the October 26-November 1, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.