![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Houses of Pain

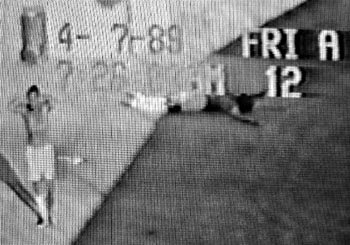

Tape Measure: A videotape obtained by Metro shows that after guards at Corcoran State Prison shot William Martinez in the back, they left him dying on the ground for nine minutes. Dan Lungren's office provided evidence to the court that Martinez was removed from the yard after only 18 seconds. Taking his punitive law-and-order ideology to the extreme, Dan Lungren instructed his office to ignore murderous conditions in California's prisons By Jim Rendon

ON AN EARLY MORNING in April 1989, William Thomas Martinez walked out onto the tiny wedge-shaped yard in the secure housing unit of Corcoran State Prison to get a little exercise. A few moments later, Pedro Lomeli, another inmate, walked onto the yard. Martinez charged him, fists flying. The two punched and kicked each other for about 10 seconds. A few ticks of the clock later, a guard shot Martinez in the back. Within an hour, the inmate was pronounced dead. The last time the two inmates had been in the yard together, Lomeli had attacked Martinez, and on this April morning, the guards had deliberately arranged for the two enemies to be in the yard at the same time. A later investigation revealed that guards at Corcoran regularly staged fights between rival inmates, just for kicks. No guards were prosecuted or disciplined for the event. Martinez's 1989 death marked the beginning of a long, violent period in California's prison system--a decade of woundings, shootings and abuse. For years, all of this violence was ignored by California's top law enforcement official, Attorney General Dan Lungren. After determining that guards had injured and killed an alarmingly high number of inmates, the FBI was finally forced to begin its own outside investigation in 1994. At the same time, Lungren and his deputies vigorously defended violent guards, as well as the Department of Corrections' policies, fighting a series of civil suits which the state ultimately lost. When the Martinez family sued the state of California, Lungren's office argued that the shooting was justified. Between 1989 and 1998, 36 inmates were shot dead by guards in California prisons, and hundreds were wounded. Not one of these shootings was prosecuted by the state. Guards With Guns

THE EPICENTER of the violence has been Corcoran State Prison, a maximum-security facility located in Kings County. Seven inmates have been killed by guards at Corcoran over the past nine years--more than at any other prison in the nation. All the shooting deaths took place in the Secure Housing Unit, which is reserved for the hardest cases in the prison system--gang members and those who break rules on the inside. Inmates involved in everyday fistfights were regularly fired upon with a 37mm nonlethal wood-block gun. When that failed to stop the unarmed inmates from causing trouble, guards fired real bullets from 9mm and 14mm rifles. Department of Corrections rules allowed guards to fire on inmates if they believe one of the inmates is in danger of a serious injury. The prison guard who shot Martinez said he fired because Martinez could have caused serious damage to Lomeli by kicking him in the head. But on a Department of Corrections videotape of the incident, which Metro obtained, Martinez is clearly seen to be walking away from Lomeli when he is shot in the back and drops to the ground. That videotape shows that guards left Martinez on the ground for nine minutes before taking him to the hospital. A tape of the incident was turned over to the attorney general's office, which passed it along to the state's Department of Justice. But in a deposition filed with the court, Stephen O'Clair, a criminalist with the Department of Justice who reviewed the videotape that Lungren's office supplied, said that only 18 seconds elapse between the moment when Martinez was shot and when he was removed from the yard. Bob Navarro, an attorney suing the state in a separate shooting incident at Corcoran, believes another videotape may exist. That, he believes, would constitute evidence that Lungren's office submitted doctored evidence. He has spent months looking for that tape, but come up empty-handed. "I have not had any experience in another case where something similar has occurred," he says. O'Clair says he has been instructed by the attorney general's office not to talk to the media about the Martinez case or the videotapes. Antonio Radillo, the deputy attorney general who handled the case, referred inquiries to the attorney general's communication office, which has ignored numerous requests for information for this article. Federal Judge Edward Dean Price said the videotape which showed guards coming to Martinez's aid almost immediately after he was shot was "one of the most helpful bits of evidence" in the case. Judge Price dismissed the case, and he has since died.

Political Prisons: On Attorney General Dan Lungren's watch, more prisoners were killed in California jails than in every other prison in the nation combined. Blind Injustice

IN CORCORAN'S FIRST year of operation, guards fired at inmates with wood-block guns 662 times, and with rifles 47 times, according to published reports in the Los Angeles Times. More than 200 inmates were injured, and two prisoners were killed. Many of these incidents--as well as shootings and killings at Pelican Bay and several shootings at Folsom and Calipatria--resulted in civil suits that were defended by the attorney general's office. In the years following, the situation at Corcoran improved little. According to the Department of Corrections, in 1993 and 1994 at Corcoran alone, 15 inmates were seriously wounded and four were shot dead. In late 1994, the Orange County Register calculated the number of inmates who'd been killed in the state. Between 1989 and 1994, according to the article, there were three times as many shooting deaths in California state prisons as in all 49 states and the federal prison system combined. That story was followed by exposés by the LA Times and 60 Minutes, detailing many of the shootings. Only after these stories broke did Lungren's office peek into the Department of Corrections, launching an investigation which focused entirely on two specific incidents and ignored broader questions of systemwide guard violence. After 18 months, it produced no indictments. Finally, on Oct. 9, 1998, a Kings County grand jury handed down five indictments against guards who used one inmate to rape other inmates, after an investigation which the attorney general's office aided. But critics say this should have happened years ago. "They should be ashamed of themselves," says Catherine Campbell, an attorney suing the state over a 1994 inmate shooting which the attorney general's office is defending. "He already had all the information he needed to go after a criminal case." The only investigation which Lungren's office initiated, begun in 1996, focused on an incident in which guards dragged a number of inmates onto the yard and, hiding their own faces, proceeded to kick and beat the prisoners. Although the Department of Corrections is disciplining six guards for the incident, Lungren's office did not find enough evidence to indict. As part of its inquiry, the attorney general's office investigated another incident in which inmates arriving from Calipatria State Prison were met by a group of guards who then beat them severely. This time the attorney general's office reviewed the local DA's decision to not prosecute and agreed that there was no case. Al Fox, a lead investigator for the attorney general's office, subsequently took a higher-paying job with the Department of Corrections, the very agency he had just finished investigating. Indifferent Strokes

TURNING A BLIND eye to the abuse of inmates is part of a long pattern in Lungren's office, says Gwynnae Byrd. The principal consultant in a series of hearings on prison violence held by the state Legislature this summer, Byrd says Lungren let prison guards off the hook no matter what they did. "The attorney general had no interest in pursuing wrongdoing on the part of law enforcement," she says. "That attitude prevailed whether it was killing [of inmates], beatings, rape, whatever." Though the Sacramento hearings centered on problems within the Department of Corrections, Byrd says she wants more time to look into Lungren's indifference to violence in the prison system. Matt Ross, a spokesman for the attorney general's office, says Lungren did not want to interfere with the ongoing FBI investigation of the shootings, and therefore focused on the beating incident in his investigation. "We did not want to step on anyone's toes," Ross says. But Nick Rossi, an FBI spokesperson, says that the state could have investigated on its own. "State and federal investigations are often overlapping," he says. At no time did the agency ask the attorney general's office to limit its inquiry, Rossi says. In mid-July of this year, James Maddock, head of the FBI's Sacramento office, confirmed that the decision not to investigate these cases was Lungren's, not the FBI's. In a letter to state Sen. Ruben Ayala, who co-chaired the prison hearings, Maddock denied ever asking Lungren's office to limit its investigation. Ross insists that it was not the attorney general's place to investigate the shootings, indicating that local district attorneys should handle the cases. But in case after case, local DAs did not follow through on the shootings. And Lungren's office ignored requests for investigation by inmates, constituents and attorneys. Ultimately, Lungren demonstrated that his office does have a role to play when he stepped in to review two cases. Though the number of prison killings exploded throughout Lungren's tenure, AG spokesman Ross says investigating those shootings "would have been a waste of taxpayer money." During Lungren's tenure, the state lost or settled five major class-action suits over the treatment of inmates. Many of these cases alleged unconstitutionally cruel behavior on the part of the Department of Corrections. In each case, Lungren backed the department. "The California attorney general's office defends whatever happens at the Department of Corrections," says Elizabeth Alexander, director of the National Prison Project of the ACLU. That is not the way things have to be, she adds. In New Mexico, 1,100 prisoners took over an entire prison in 1980, taking guards hostage and killing 33 people in three days. In the riot's aftermath, Attorney General Jeff Bingaman--now a U.S. senator--used his office to force the state's corrections department to correct the conditions that led to the riot. Bingaman conducted a full investigation of the riot and of prison conditions. Mark Donatelli, one of the attorneys who sued the state over the riot, says the suits were settled quickly without a lengthy trial, and the attorney general's office did its best to ensure that problems in the prison system were addressed. "That is a shining example of an attorney general stepping forward to address problems," Alexander says--a stark contrast to Lungren's decision to sit on his hands. In other states, she says, staffers in offices of attorneys general work to ensure that problems are fixed. Instead of complying with the court and solving serious problems, Lungren's office just keeps fighting, she says. In a statement issued last week, at the close of the legislative hearings, San Jose's state Sen. John Vasconcellos roundly criticized the Department of Corrections' history of violence, and Lungren's handling of the case. His statement called for massive, immediate changes, and indicates that further legislative actions may be forthcoming. "When matters got out to the public, resulting in television and newspaper exposes, both the Department and the Attorney General's office announced thorough and comprehensive investigations. Yet, instead of breaking this pattern of cover-up, they reinforced it, producing nothing, except lies, to the people of California." [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()