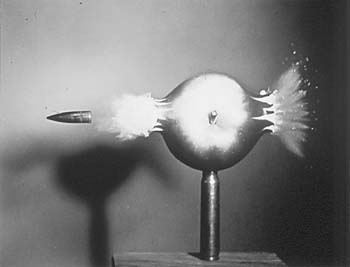

William Tell in the 21st Century: Harold Edgerton's 1964 photograph '.30 Bullet Piercing an Apple' is part of a series deconstructing high-speed events with the aid of stroboscopes.

Artists use and abuse technology at the San Jose Museum of Art's 'Alternating Currents' show

By Ann Elliott Sherman

A VERY BROAD overview of technology's influence upon American art of the last 40 years, the San Jose Museum of Art's Alternating Currents: Art in the Age of Technology produces the same kind of overstimulated daze as a theme-park thrill ride. The mind latches on to a few fun tricks and interesting details, of which there are many, but not much coherent thought results.

Neither a chronological history of technology's employ within art genres or movements nor a tracing of changing attitudes toward technology, the latest installment from the Whitney Museum is a sampler of art using technology as subject, as raw material, as perceptive experiment.

The show is arranged in three sections. The first of these, "Industry and Consequence," presents work that uses industrial materials and/or imagery to comment upon the postindustrial world. Significantly, this segment is dominated by three goliath sculptures--Claes Oldenburg's Ice Bag, Jonathan Borofsky's Hammering Man at 2715346 and Tom Otterness' The Tables--putting the viewer in the position of submitting to the inevitable.

The shape-shifting result of Oldenburg's collaboration with Disney "imagineers" takes the artist's ironic fascination with the effluvia of American postindustrial affluence one step further, capturing an ice bag's particular marriage of form and function in entertaining fashion.

The threats of nature and industry converge in city life in Otterness' cautionary triptych of outsized metal picnic tables aswarm with tiny cast-bronze cartoonlike figures going about the business of destruction/survival. The Tables is interactive in a subversively traditional sense, without a switch or mouse in sight.

Otterness has used functional design, scale, context and association to involve the viewer and affect perception. The first sensation upon sitting on one of the built-in benches is of being a child at the grownups' table. Then, looking down upon the little scenes in whatever sequence s/he pleases, the viewer puts together the overall story with the omnipotence of a kid playing with toys. Otterness serves up an epic that blends "high" and "low" culture in a manner that Brecht--who, appropriately enough, said that the "Fate of Man is now Man himself"--would applaud.

The second part of the show, aptly titled "Challenging Perceptions," presents pieces that toy with technology, our psyches and optic nerves in equal measure. Most are fun in and of themselves, which is lucky, since the way they fit into the artistic philosophies and cultural zeitgeist of their time isn't always explained.

It's doubtful, however, that many will care about such academic i-dotting with diversions such as Harold Edgerton's stroboscopic photographs that freeze a splash or deconstruct a blur of wings, Earl Reiback's box of dancing lights or the now-you-see-me, now-you-don't fun-house effect of Buky Schwartz' Yellow Triangle video installation.

These and other pieces do raise questions about technological enhancement or manipulation of sensory information, but collectively they threaten to overload the synapses. Those works that require a more isolated installation are better able to transmit the wonder and liberation from convention inherent in such exploratory creations.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The SJ Museum of Art reopens its historic core.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

BY THE LAST SEGMENT of the show, technology is more or less a given, one of many things put in service to the artists' "Message and Narrative." If it feels less historic, well, it is--almost all the work here dates from the '80s onward. The usual techno suspects are rounded up--Nam June Paik, Jenny Holzer--only to get upstaged. Pepón Osorio's incorporation of videos in the shrine honoring Angel: The Shoe Shiner make us really see someone whose status otherwise renders him invisible.

Holzer's Unex Sign #1 stems from her work displaying text on the huge public signs in New York's Times Square, but the in-your-face power of having someone's slightly off-kilter truisms insinuated into your own consciousness via a public medium is lacking here. Instead of the original subversion of commercial communication, it plays like an artier version of an electronic beer sign in a basement rec room.

Tony Oursler's disembodied emotional projections do give pause. A rag doll is hung in effigy, a laser-disc image of a woman's painfully unsuccessful attempts to contain her tears projected on its empty face. Yes, it's just a Crying Doll, but try to watch without feeling at least a little like one of Kitty Genovese's neighbors.

San Jose artist Joel Slayton's installation for the Cathedral Sculpture Garden, To Not See a Thing, aims to tie all three parts of the show together. Through glass now tinted intensely red, a Plexiglas box resting on a pedestal in the enclosed patio can be seen. Or one can choose the view from surveillance cameras aimed at the box.

To the left of the cameras, a small maquette of the box has been wired to register the spatial coordinates that track its movement when physically examined by the viewer. These are translated into a digital representation on a computer programmed to record the box's movements during the run of the show, to later be played back and incorporated into the piece. To Not See a Thing might make a point about reliance upon video accounts or virtual recreations of reality diminishing our actual perceptive acuity or rendering it obsolete. Or maybe viewers will watch the screens to escape the red glare.

Alternating Currents will be around for a year--like the best thrill rides, it warrants a return trip, if only to get a crack at the 30-foot-long interactive timeline wall designed to connect the dots between watershed events in art, technology and culture.

Alternating Currents runs through Oct. 18, 1998, at the San Jose Museum of Art, 110 S. Market St. (408/271-6840)

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)