Robert Scheer

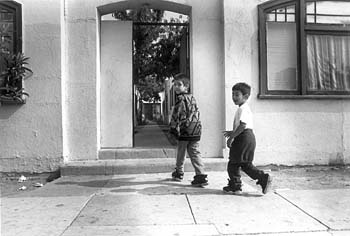

One of Gilbert Marosi's problematic rental properties, located at 22 South Fourth Street in downtown San Jose, where code inspectors say complaints of rats, roaches and leaks have gone unresolved for years.

With vacancy rates edging close to 1 percent , it's a scary time to be a renter in Silicon Valley. So throw the deadbolts, dim the lights and pull the covers way up to your chin. There are horrors out there.

By Michael Learmonth

IN THE WORKING-CLASS and well-to-do neighborhoods of Silicon Valley, house after house is festooned with make-believe frights: cackling jack-o-lanterns, Kmart cobwebs and tombstones inscribed with ominous epitaphs. But the true haunted houses in Silicon Valley need no decoration. Scaly-tailed rats saunter through baseboard holes. The autumn wind whistles through cracked windows and broken frames. And the steady plop-plop-plop isn't the beat of a telltale heart but the sound of autumn's first rain hitting the bedroom carpet.

With vacancy rates hovering at a stingy 1 percent, it's a scary time to be a renter in Silicon Valley. The price of an average two-bedroom apartment has soared to almost $1,500 per month. Renters know that any provocation can lead to a sudden unexplained rent hike or, even worse, the 30-day eviction notice. Still, they cling to their homes in fear. They know that for every apartment, no matter how ghastly, there are legions of dispossessed waiting in line to take their place.

In this, the renters' time of need, there are landlords all too willing to turn a house of horror into a fast buck. In the absence of a healthy balance between supply and demand, they feel free to wring extra cash from the poor, let dwellings deteriorate into haunting conditions and give walking papers to any soul foolish enough to complain.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The global economy, local zoning decisions and California's tax revolt bear responsibility for skyrocketing rents and housing scarcity.

Where to go for help with landlord/tenant disputes.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Love It or Leave It

EVEN IN THE MIDST of a blighted block, the residents of 22 S. Fourth St. in San Jose manage to give the one-story stucco apartment complex some charm. The windows facing the street are blocked from view with colorful Mexican blankets. The black steel gate on the street opens into a long courtyard, about 6 feet wide. Next to the path, some plants grow, and in places the dirt is turned over in an earnest attempt at gardening. Most of the windows are open, and the steady beat of tejano music and the smell of cooking chicken fill the air.

But this building has been cited by San Jose city code inspectors 12 times since 1988 for infractions ranging from rat infestations to festering piles of trash. And as a tenant in apartment D found out, the owner of the property, Gilbert Marosi, doesn't take too kindly to tenants' complaints.

Maria Elena Cerda, her husband and three children moved into the apartment in June 1995. Cerda kept a clean house, her attorney says, constantly mopping the floor and wiping down the kitchen in a Sisyphean battle to stay ahead of the rat turds. After she had lived in the apartment 17 months, Cerda complained to the apartment manager that her bedroom window had fallen out of its frame and that her bathroom sink had become separated from the wall.

On Nov. 18, 1996, a maintenance man showed up, taping a brown plastic bag over the broken window and doing nothing about the sink.

The next month, Cerda told Marosi that she was withholding December's rent until repairs were made on the window and the sink. Shortly thereafter, Marosi informed Cerda that he was increasing her rent from $485 to $725 per month.

In January, Cerda was confronted with a few other unpleasantries. Her heater was broken, and that little leak in the ceiling had become a deluge. Cerda informed the manager of the problem, then called the fire department. When firefighters arrived, they found a ceiling about to cave in and informed Cerda the building was unsafe. An hour later, a code enforcement inspector arrived and issued a compliance order to Marosi. Marosi then informed Cerda and her family they had 10 days to leave.

"She was a pain in the ass," Marosi now says of his former tenant. "I had already contracted with a roofer, but she called the fire department, the police and code enforcement, and everyone got on my tail. She was supposed to call me first." Marosi still bristles over it. "I gave her a 30-day notice, and she went bonkers."

Marosi took Cerda to court to have his eviction demand enforced, but Cerda's attorneys from Community Legal Services were able to settle with Marosi and buy her an extra five months to move out.

"Landlords sometimes get angry at tenants for making complaints to this office," says Larry Boales of the city's Rental Dispute and Mediation Program. "We try to get people to get together and cool off, but retaliatory evictions are illegal."

Cerda moved as soon as she could, which was several months later, and a new crop of tenants moved into 22 S. Fourth St.

Marosi is well known among city authorities. He held a press conference last year in the lobby outside the offices of Mayor Hammer and the City Council to protest a $10,000 fine after the city threw the book at him for a garage he was illegally renting out as a "granny unit."

"I pissed off Susan Hammer no end," Marosi now says proudly. "I identified 120 units in the city with equal granny units just like mine."

Marosi was also named in the suit the city brought last year against the owners of 92 fourplexes in the long-troubled Santee neighborhood of East San Jose. Today, the city has a satellite office in Santee with two full-time building inspectors, just to keep landlords in line.

City code inspectors say Marosi's MO is fairly simple: he rents to mostly poor, Spanish-speaking tenants. When they complain, Marosi evicts them and rotates others in.

The city forced Marosi and other landlords in Santee to plant grass, paint over graffiti and landscape their properties. As a result, Marosi's two buildings have a lush layer of sod in front, but the dusty, trash-strewn conditions in the back remain. When he does make repairs, one inspector says, "he does just enough to keep himself clean. We'll find out when it starts raining how he did on the roof repairs."

Robert Scheer

The Tudor-style Los Altos residence of local landlord Gilbert Marosi is a far cry from some of his rental properties throughout the county, where charges of rats and filth have gotten him fined and sued by the city of San Jose.

For the record, Marosi owns 16 properties in Santa Clara County and lives in a home in Los Altos the county assessor values at $748,683.

Currently there are seven men living in the apartment, splitting a $700-a-month rent.

The laundry list of unresolved code violations on the books at the city's code enforcement department still includes roaches, rats, leaky faucets, the falling ceiling and a carport full of trash. But despite Marosi's mounting code citations for 22 S. Fourth St., he's poised to make some serious money when he sells it. Marosi's property sits in the middle of the city of San Jose's preferred site for the new city hall.

I ask one of the new tenants of apartment D in Spanish if he's had any particular problems since he moved in. He looks at me confused. He is, after all, paying $100 a month rent in Silicon Valley. Finally, he walks me over to the side of the unit to an obviously needed repair he imagines will be fixed sometime soon. He points to Cerda's old bedroom window, now covered with an aluminum screen crudely nailed to the frame. "This window is broken," he says. "It won't close."

The Section 8 Ball

WHEN HELEN LEE signed a lease on a three-bedroom apartment at 4415 Norwalk Drive in San Jose, she felt lucky. Her rent was $1,200 a month, but she would only have to pay $116 of it. Lee, an African American single mother of three teenagers, is one of 9,000 holders of a Section 8 voucher (out of an estimated 50,000 who are poor enough to qualify) from the Housing Authority of the county of Santa Clara.

For the poorest of the poor, a Section 8 voucher is like a winning lottery ticket. Owners of the voucher pay only one-third of their monthly income for rent, while the Housing Authority chips in the rest. The Department of Housing and Urban Development sets the grant levels according to average rent rates, but with rents rising so fast, the grants are often a few hundred dollars less than what a landlord could expect to get for an apartment on the open market.

Landlord Bharat Shah signed a contract with Lee and the Housing Authority in September 1995 and agreed to accept two checks each month--$116 from Lee and $1,084 from the county--for the apartment at 4415 Norwalk.

But Shah, who has access to his tenant's financial information from Housing Authority paperwork, apparently felt that this wasn't enough. Soon after the ink dried on the contract in September 1995, Shah started slipping postcards in Lee's mailbox demanding that she pay extra money each month or, he threatened, he would terminate her Section 8 contract, according to Lee's statements to attorneys.

Lee, a soft-spoken woman who looks away when you address her directly, says she was intimidated. She agreed to pay him a $1,000 security deposit and an extra $50 each month. She was poor and getting poorer. A month later, the Housing Authority noted that fact and reduced the amount she had to pay Shah from $116 to $75 a month. Shah decided to raise his demands on the postcards to Lee, from $50 to $166 a month.

Sometimes, according to Lee, Shah applied a portion of Lee's rent payment to repairs without telling her, and then charged her a $50 late fee on the balance.

Finally, in January 1997, Shah sent both Lee and the Housing Authority a notice that he was evicting her family from the apartment. Since, in San Jose, landlords must show good cause to evict from Section 8 and rent-controlled apartments, Lee was able to challenge the eviction in court.

And Shah soon found out he had made a mistake most landlord-extortionists take pains to avoid. Lee had been saving those handwritten notes Shah liked to place in her mailbox, and she happily handed them over to Angelique Gaeta, an attorney at Community Legal Services.

"It's unique that a landlord would leave such a paper trail," Gaeta comments. "Usually landlords are savvy businessmen who know the last thing you want to do is leave a paper trail that you are breaking the law."

Gaeta settled with Shah for $2,500 of the $3,000 he extorted from Lee over 17 months, which Lee received. There were no damages awarded, and no criminal complaint was filed against Shah. Gaeta says Shah's practice is widespread in Silicon Valley. "It's a big problem here, and a lot of people are willing to pay that extra money," she says. "I guess Shah thought [Lee] would be a pushover, that she wouldn't take action."

The Potty Mouth

IT'S NOT EVERY LANDLORD who gets fined $20,000 by the city of San Jose and is given nine months to sell three houses. But then not every landlord has the rhetorical grace of Allan Mueller, who explained to me over the phone, "I basically rent to fags and niggers."

The College Park landlord was equally candid in a deposition given to a San Jose city attorney earlier this year. He said his ideal tenant had to have special qualities: enough money to pay the rent and the deposit, and they had to be an "introvert." Mueller explained that an "extrovert" would be the type of renter eager to impress a potential landlord with "what a wonderful tenant they were and how many jobs they had." An introvert, said Mueller, "would be one who would come and basically beg for a place to stay."

Mueller began buying properties on the shady blocks of Victorian and mission-style homes across from the Rose Garden in the late 1970s. Over the years, as the housing shortage grew more desperate, he chopped them up into small units, renting them out to his own special type of tenant. Over the years, Mueller rented four houses on one block to all comers. Rent was collected weekly, and turnover was high. Between November 1993 and August 1995, Mueller's records show that 102 people lived in those four houses. To skirt city housing ordinances that prohibit boarding houses in the neighborhood, he assigned the people living in the homes to "families." The houses were listed as inhabited by "The Family of Big Pink," "Freddy's Family," "Turtle Pond Family" and "Uncle Al's Family."

Mueller, never shy about his philosophy, told Kayla Kurucz, a neighbor and president of the College Park Neighborhood Association who complained about the tenants, that it was she who chose to live in a "shitty neighborhood" and promised to rent the house next to Kurucz to "drug addicts, felons and hookers."

Mueller apparently also has an interest in social engineering. In the deposition he outlined his approach. "Well, most of my tenants are color- and gender-challenged, so we try and match them up somewhat along those lines."

The city attorney then asked if he intentionally grouped his tenants by race, at which point Mueller's attorney asked for a recess.

When he came back, Mueller said, "Race has nothing to do with it." But then he continued, "I have one house that had mainly lesbians and gays in it. I have another house that had mainly Neo-Nazis, right-wing extremists, that kind of thing."

But Mueller sees himself and landlords like him as part of the solution to the Silicon Valley housing crisis. By making him sell three houses, he says, the city shows it doesn't care about providing housing for poor people.

"San Jose can give a shit about poor people," Mueller says in a phone interview. "The yuppies want their little places of San Jose for themselves. I'm putting my people out on the street this week. They've got no place to go."

Brad Solberg, an SJSU student who lives in the house next to 812 Myrtle, says one batch of residents of the house next-door broke through the fence so they could take a shortcut to buy liquor at the Bell Market on Emory Street. At night, when Solberg and friends sat on their porch, they watched a prostitute who lived next-door, whom they called "Alameda Carol," ply her trade in the neighborhood.

Solberg says he's had few troubles with the tenants, and his friend Tony Hall says he found his car undisturbed after he left it unlocked overnight.

San Jose Police Lt. Dennis Luca wasn't so lucky. His squad car was broken into in the neighborhood, and his police revolver recovered in one of Mueller's boarding houses on Emory Street.

The 807-Unit Gorilla

RICHARD GREGERSEN owns 807 apartments in Santa Clara County alone, so when he throws his weight around, it doesn't go unnoticed. Last year when he decided to jack up rents 30 percent, he ticked off a lot of people, including one very intense man named Mark Sherwood. An electronics salesman and single father of two, Sherwood received notice that rent for his three-bedroom apartment in Cupertino was suddenly increasing from $1,100 to $1,474. He placed a call to Gregersen immediately to discuss the increase. The building manager returned his call and told him bluntly he could "pay or get out."

Unbeknown to Gregersen, he had just created a monster.

Sherwood called a local television station and held up his notice of increase for everyone to see on the evening news. Then he went door to door in the Westwood Townhomes in Cupertino and convinced 64 out of 114 families to join the Westwood Tenants Union.

Gregersen finally agreed to meet with Sherwood and representatives from the union, and they hammered out an 11-point agreement that rescinded the 30 percent increase and limited future increases to 15 percent or to current market rate.

The deal also delved into maintenance problems at Westwood. The pool, for example, had been closed by the health department, and the roof in two apartments caved in during a rainstorm. One laundry room was closed by Cupertino building inspectors for seven months.

The agreement with Westwood tenants proved to be only the beginning. Sherwood had metamorphosed almost overnight from mild-mannered Republican into tenants' rights superhero. Sherwood, who talks like a lawyer but never went to college, began helping other Westwood tenants and pushing for new rent-control laws in Fremont, Campbell and Palo Alto. Tenants of the Highlander, another Gregersen building, withheld rent en masse until certain "habitability" issues were addressed.

Then Sherwood got a call from another Westwood tenant, Bill Alden. Alden had come home to his apartment that day, smelled something funny and discovered that a maintenance man had sprayed the pesticide Diazinon inside his apartment, in the company of his two parrots.

Sherwood called the Santa Clara County Department of Agriculture.

"The tenants were advised not to go back into their unit until it was industrially cleaned," Sherwood says.

Diazinon, which is toxic to humans and deadly to birds, is an insecticide. Bill and Lisa Alden took their pet parrots, Alex and Nina, to the vet for the antidote--a shot of atropine.

"He [Gregersen] compensated us for the [parrots'] toys and for the vet and food," Lisa Alden says. "He was pretty nice about it."

This year, the rent for the Aldens' two-bedroom unit, however, went up from $1,167 to $1,342.

After the Diazinon incident, Sherwood got word his mother was dying of cancer in Los Angeles. He dropped a check by the Westwood management office before he left and asked that they hold it a few days. He was going to have to pay for his mother's cancer treatments and needed to transfer money into his checking account.

When he got back to Cupertino on Feb. 4, his rent check had bounced, so he wrote another check. Gregersen refused to accept it and began eviction proceedings.

Sherwood challenged the eviction, and Gregersen agreed to terminate it if he would agree to leave voluntarily. That month Sherwood relaunched his tenants' group as the California Tenants Association, which now boasts more than 4,000 dues-paying members. Sherwood hopes to attract some of California's 12 million renters to the group.

"I'm not some rent-control fanatic," Sherwood says. "We do not have a free and open market."

With or without Sherwood as a tenant, Gregersen faces bigger problems. The owner of buildings like the Westwood, the Highlander, the Summerwind, Inn at Pasatiempo, Sandalwood Apartments, Monterey Apartments and Terrace Apartments, Gregersen is accused of using especially creative lease terms to help him exact a pound of flesh at move-out time. Now the Santa Clara County District Attorney has filed a civil complaint to stop and seeks $1 million in damages.

The district attorney alleges that Gregersen used "rental agreements with unlawful terms" and "improper deductions from security deposits in the form of 'turnover fees.' "

"A far as we're concerned, that's a made-up term," says Robin Wakshull, a Santa Clara County deputy district attorney.

Attack of the Green Slime

DAISY IRENE WOOD, a hearing-impaired woman in her 60s, lived for 10 years in the heart of sleepy suburban Santa Clara in a small three-bedroom home which became a house of horrors. A year ago, according to next-door neighbor Steve Cabral, there were pieces of mildewed carpeting and an old Opel GT rotting in the yard. Inside the house, an algae film covered the surfaces. When it rained, water leaked from the ceilings and soaked the rugs. Wood, 61, had to abandon the master bedroom after a rainstorm left inches of standing water on the bedroom floor. The wet carpets became a de facto cockroach ranch.

After the rainstorm, Wood called her landlords, Robert and Helen Hsin, and informed them that she would be withholding rent until the leaky roof and a broken toilet, sink and window were repaired.

The Hsins' reply? "We do not have the money to make the repair. You live in the house; you fix it."

But Wood was in no condition to make repairs to the house. Her only source of income was a disability check. To make rent, she borrowed money from her two daughters.

When she began to withhold rent, the Hsins told Wood, who is nearly deaf and had recently suffered two heart attacks, that she must pay them something or the "government" would come and evict her, Wood says.

Wood complied, paying the Hsins $300 of her $1,100 monthly rent.

Then, the ceiling fell in one of the bedrooms. Wood paid a roofer $602 to fix the roof and was never reimbursed.

According to her attorney, Rubén Pizarro of Community Legal Services, on the few occasions when the Hsins did make repairs, they raised the rent.

"She did not pay rent for two years," Helen Hsin says of her former tenant. Hsin says that she allowed Wood to stay because "I didn't want to make an old person move out on the street."

Wood's daughter Sandy Cates says her mother had an agreement with the Hsins to pay rent only on the parts of the house that were liveable.

When the building inspectors came, they found the house "untenable" and cited the Hsins for 22 code violations.

The Hsins claim they wanted to repair the damage, but Wood prevented them from surveying the damage by changing the locks.

The city of Santa Clara gave the Hsins 30 days to repair the damage, and Wood's attorney settled for $2,225 in restitution.

The Hsins fixed the roof and raised the rent, and Wood had to leave.

Once Wood was gone from the house, the Hsins spent $20,000 to gut the place, pulling out the fixtures, the walls and the wood floors, which had buckled from the standing water.

Today, their daughter Jenny Hsin lives in the tidy little one-story, now painted cream with teal trim. There is a freshly cut lawn and a garden with withering sunflower stalks.

The elder Hsins, both in their 60s, say they need the income from renting the house to help support them. "I use that for my retirement," Helen Hsin says.

Daisy Wood left the decrepit conditions on Francis Avenue and in the end chose to leave the housing horrors of Silicon Valley altogether. Today she lives with a sister in Half Moon Bay, where she has no phone, but her daughter says she finally has a protective roof over her head.

Shelter Skelter

IN THE DAYS BEFORE housing shortages, tenants faced with problem landlords had an attractive option: give 30 days' notice and walk. Today, in Silicon Valley, more and more tenants are choosing to stay and fight in mediation or the courts.

"I think it used to be that people with a leaky roof could move to a better apartment," says Larry Boales of San Jose's Rental Dispute and Mediation. "Now, it's harder to find an apartment so it's more of an incentive (for tenants) to deal with a problem."

Boales has seen his caseload shoot up in the past three years, from 33 cases in fiscal 1995 to 75 in 1996 to 61 cases in just the first six months of this year.

City Attorney Joan Gallo says that her office is working closely with code enforcement to bring the scofflaw landlords into compliance with city regulations. Four of the Santee neighborhood landlords eventually got jailtime for their consistently dilapitaded buildings. One was banned from ever owning rental property in San Jose.

"What we have is a very coordinated effort between the department of code enforcement and the city attorney," says Gallo.

Tamara Dahn, executive director of Community Legal Services, says 59 percent of the cases her office handles are housing-related.

"The cases are becoming more and more difficult," Dahn says. "Once code enforcement gets a landlord to fix the property, the client can no longer afford to live there."

One thing Dahn says is certain: For every tenant they try to help, there are others too afraid to come forward.

"People are living in garages and basements," Dahn says. "They are just happy to have a roof over their heads. Period."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)