![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)

[ Music Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

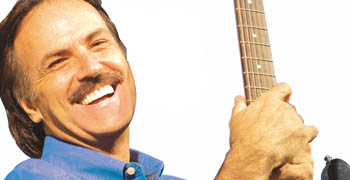

Photograph by Anthony Pigeon Hey Joe We can't all be Smash Mouth or the Doobie Brothers--and maybe we don't want to be. Joe Sharino is one valley rock & roller who defines success one festival at a time. By Todd Inoue MOST OF THE PEOPLE MILLING about at the Santa Clara Art & Wine Festival didn't come here to rock. They are more interested in crushed grapes and country crafts. Vintners fill the glasses of tipsy suburbanites clutching handmade pottery and "dirty/clean" dishwasher magnets. Local jazz and rock bands have been serenading the folks all day inside Central Park's bullring-shaped amphitheater. Consumers of all ages, waist sizes and bank accounts sit a spell in the shade of the creeping ivy, but it isn't until the Joe Sharino Band takes the stage that the crowd gets off its collective ass, braves the mid-September sun and transforms the sleepy festival into a full-blown fiesta. Maybe it's the wine, maybe it's the sense that summer's end is near, but the Joe Sharino Band throws a switch that spurs the party animals to stampede. Sharino and his band of merry men--drummer Andy Morales, keyboardist Peter Cor and saxophonist Mark Belshaw--play a set of party-rock classics like Bob Seger's "Old Time Rock & Roll," Jerry Lee Lewis' "Great Balls of Fire" and the Commodores' "Brick House." The band merges the '60s-'70s hits that everyone knows with an '80s or '90s song or two. The newest number is Santana's "Smooth," which the fans take as their cue to fall into line and dance the Electric Slide. Sharino rips a respectable guitar solo during the song's break. The temperature level skyrockets during revved-up songs like the Doobie Brothers "China Grove" and Lynyrd Skynyrd's "Sweet Home Alabama." Sharino and his band have been playing for nearly three hours, and the crowd--numbering 800 people--isn't going anywhere. A conga line opens up during "Tequila" that stretches the length of the amphitheater. Every song is instantly recognizable, and everyone--from a Vietnamese cowboy to a great-grandmother to jaded teens--gets moving. When Sharino sets off a confetti cannon during Kenny Loggins' "Footloose," the place goes bananas. Belshaw leaves the stage to solo in the crowd. Sharino exudes laid-back cool in black jeans and a Hawaiian shirt. His voice has the same Ventura Highway feel as Loggins' or Jackson Browne's. Every now and then, Sharino will lean over to whisper something to his band mates and crack a 100-watt smile. In front of the stage, regulars cluster, singing every song, working up a sweat. During a set break, I recognize one of them, a friend's older sister. She's dabbing her brow and looking for a water source. I want answers. Chris, I ask, "What the hell are you doing here? What is up with this guy with the mustache, feathered hair and parade of hits?" Chris' answer is pure nostalgia. Chris remembers sneaking into Campbell clubs when she was 18, just to see Sharino play. She's 42 now and a mother. She doesn't go out as much as she used to, but she made a trek to see Joe do his thing. "Were you here earlier? Remember how everyone was sitting down?" Chris asks. "Joe gets everyone up and dancing." Who the heck is this guy? And why is he so damn popular? Joe Familiar Look at that picture. You've seen him. If you're over 40, Joe Sharino played your high school dance. If you're young, you danced in your parents' arms at a wedding, art festival or chili cook-off while he jammed. Maybe that was Sharino singing "Good Lovin'" in the parking lot of Candlestick, Spartan Stadium and other houses of worship. He's played every possible food-related festival within a 100-mile radius. Zucchini, garlic, artichoke, broccoli, strawberry, squid, pumpkin, prune and Brussels sprouts--you name it, he's played it. Here's what is known about Joe Sharino. He's booked until 2004. He and his band play 90 shows a year and turn down 275. When the Joe Sharino Band "four-walls," that is, rents a hotel ballroom for a concert, it sells out. His annual pre-New Year's Eve show at the Coconut Grove in Santa Cruz--a tradition that stretches back to 1984--sells out 1,000 tickets at $35 a pop. His email list is 3,200 names deep, and his fans are some of the most dedicated party people in the South Bay. He owns two houses--one in Santa Cruz and a 6,000-square-foot mansion in Oakhurst, near Yosemite. He's a devout Christian who teaches Bible study once a week. He married his college sweetheart and has two children: a son at Yosemite High School and a daughter at UCLA. You want to get Joe Sharino for your wedding, company party or bar mitzvah? Break the piggy bank, because he doesn't play cheap; a set of cover tunes will cost between $2,900 and $4,800, but he rocks as hard at a wedding as he does at community events. Sharino has become a commodity, one that operates on a simple philosophy: Give the people what they want.

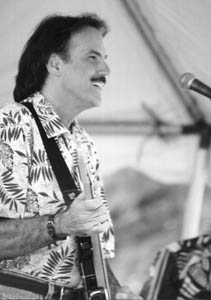

Photograph by Brian Camp

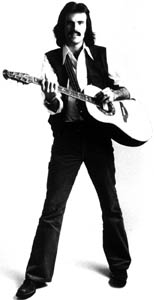

Original Joe Offstage, Sharino looks like any ordinary Joe--think Dennis Eckersley meets Magnum P.I. Minus the guitar and microphone, the man chowing down on a tuna salad opposite me at Original Joe's (my choice) looks like the kind of guy who would help you move or pick you up at the airport. His dark brown hair is showing some thinning, but he maintains his rock & roll neck warmer and Goody comb feathers. He's trim and well preserved at 48 years old. He's a huge sports nut who follows the Niners, the Lakers and the Giants, and plays golf and softball in his spare time. "We equate all our performances with a sports analogy," says Sharino, between bites. "If we can win the audience over, that's a touchdown. We actually walk over and say something to each other during songs. Like 'China Grove' on Sunday--if it's really going over, I'll walk over to the guitarist and say, 'Touchdown,' 'Gain of 43' or 'First and 10.'" In 1963, at age 8, Joe and the Sharino family left Massachusetts and settled in San Jose. The next year, he saw the Beatles on The Ed Sullivan Show, and his whole world changed. Suddenly, the accordion he had played since the age of 5 didn't look as cool. He borrowed a friend's guitar and taught himself to play ... wrong. He holds the guitar upside down, making him appear left-handed, a style he never corrected. He restrung his guitar and quickly learned Beatles, Rolling Stones and Motown songs. "I remember thinking this was the job for me," Sharino says, after watching the Beatles landmark TV debut. "Before that it was a dentist or something normal. I remember thinking it was a pipe dream. Nobody makes a living making music, and not for very long." At 14, he and his two best friends snuck backstage and met the Doors at the Santa Clara County Fairgrounds. Joe watched the show, taking in the action, lights and adulation from a new perspective. He started to make the connection between playing the guitar in the bedroom and playing the guitar to make a living. "I started writing songs that year," he says. He joined rock bands in junior high and at Willow Glen High School, playing dances and graduation parties before tiring of the constant power struggles. He attended San Jose State University and played acoustic songs for $30 a night at the Spartan Pub, where he did snoozy covers of Jim Croce, Bob Dylan and James Taylor before learning the secret to getting over: to be entertaining means being up-tempo. He started incorporating impressions and sing-alongs, and Elvis and Beatles songs, and within a year, lines were out the door. He went from $30 to $300-$400 a night. Joe quit college with one semester to graduate. Did he ever go back to get that degree? No way, he says and flashes that 100-watt smile. Prune Rock Campbell in the '70s was far from the gentrified mini-Willow Glen community it is today. Clubs like the Parlor, the Bodega, Khartoum, Smokey Mountain, the Garret, Puma's and Eli McFly's made downtown Campbell resemble Sunset Strip North, with bands loading and unloading gear. Monday nights at the Parlor, Sharino honed his nightclub act, elements of which persist in his show today. He combined cover songs, impressions, medleys and plenty of audience participation. Jim Valentine first met Joe in 1978, when he booked him at his Santa Cruz club, the Albatross. Valentine managed Sharino from 1978 to the mid-'80s. It was a crazy scene, filled with enthusiastic crowds willing to sacrifice their Monday nights to sing along, Valentine recalls. "When he backed away from the microphone during a chorus," Valentine says, "the crowd sang it back louder than the amplifiers." Joe already had a steady girlfriend, whom he married in 1982, but that didn't dissuade the lines of honeys in feathered hair and tight Chemin de Fer jeans. Valentine likens Joe's popularity with the ladies to what Dave Matthews enjoys today. "There were never more beautiful and younger women than at a Dave Matthews concert," he says. "That's what Joe Sharino had. He had gorgeous women willing to stand in line, spend their dollars on drinks and records." Being the late '70s/early '80s, drug use was rampant, and when you're a popular musician, everything is available. Sharino takes a pause when questioned about past drug use. He's worried about what his kids will think about his answer. Come on, rock & roll + '70s + Campbell clubs = plenty of doobage. Sharino concedes he dabbled--pot, mushrooms, acid, cocaine--before leaving all that alone to concentrate on music. "I quickly saw that I could end up like the others," he says. "I started playing in 1974. By that time, Jim Morrison, Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin were already dead because of drugs. I realized that I can't do drugs and still be able to sing. "Everybody dabbled, and I experimented and just decided I couldn't do it. In that era, it was common. And everything was free! I don't ever remember buying stuff. For musicians, everyone's trying to give you stuff. I was always turning it down." The Joe Sharino Band blanketed the South Bay and Santa Cruz club scenes. The group released a 7-inch single, "Thief in the Night," and did highly successful tours of Arizona. The band tested its moxie, asking for and getting opening slots for stars like B.B. King and America. Another venue it approached was casinos, and the band booked engagements at the Aladdin in Las Vegas and the Sahara in Tahoe. When Sharino did his act, full of audience participation, casino management had a fit and asked him to tone down the set. "That was like asking a fighter to take a punch and pretend he lost," Sharino says. "We lasted two weeks there. We thought it would be prestigious and a steppingstone, but it was the down-and-goers playing there instead of the up-and-comers." With his nose clean and clubs packed, the dreams that began in front of a television set and were nurtured backstage at the Doors show were starting to come true. Joe Sharino was on his way to become the next Kenny Loggins or James Taylor. Then came the big call.

Wizard in Woz Joe Sharino was sitting around his house when the phone rang. It was Steve Wozniak. Woz had made a fortune founding Apple Computers, and he was interested in putting on an event that would be the antithesis of the "me" decade, one that combined great music and Apple's vision of technology. Woz's idea became known as the US Festival. In 1982, he came up with the legendary US Festival concert lineup: 30 bands over three days, with performances by the Police, Grateful Dead, Tom Petty, the Talking Heads, the B-52's, the Ramones, the Kinks, Santana and more. Wozniak was already a fan of Sharino, whom he enlisted to play at his personal house parties and wedding reception (neat fact: the other act was Emmylou Harris). On the Wednesday before the big weekend, Woz asked Sharino to open the Saturday show. Flabbergasted, Sharino called a couple of extra guys to beef up the band, rehearsed their butts off and drove down to Southern California. "I knew Joe and immensely enjoyed his band and their music," Wozniak remembers. "His personality and onstage presence was very appealing and had great promise. Even though he wasn't as widely popular or established as the other groups on the main stage at the US Festival, I felt that he belonged there and that he would contribute to the overall entertainment of that event." Sharino was given the opening-set time, right after the national anthem. Some 200,000 people stared in his direction. "I've been performing eight years, so I don't get nervous before we play," he says. "This time, I am so nervous, because talk about a fish out of water. I've done Arizona, concert openers, casinos, but this is huge. It's 106 degrees at 12:30 in the afternoon, right after the national anthem. The PA is the biggest one I've ever seen. The stage is big as a football field. I'm meeting Bill Graham, Tom Petty, Santana, and it's people literally as far as you can see. We're the only unknowns on the bill, so we're nervous out of our minds." Wozniak personally introduced the band, saying that they were "real people." The band did a set of originals, save the last song, a cover of the Youngbloods' "Get Together." In a typical burst of exuberance, Sharino encouraged everyone to sing the chorus. It ended up being the theme song of the festival and the Showtime movie. The band's performance was covered in Rolling Stone and Time, and on NBC and ABC telecasts, as well as in the Showtime movie. Label execs were suddenly interested. "I thought, 'This is it," he says. "We felt like we won the ballgame." Head Start for Happiness Capitalizing on the sudden stardom would prove to be a daunting task. Sharino had the single and a couple of demos and not a lot of money. He decided to go to the source. Wozniak and Sharino met over lunch, and Woz wrote Sharino a check for $50,000. The band went into the studio and recorded a demo that was a mishmash of styles. A topical single about election promises, "I Wanna Be President," landed on then-new MTV but made no significant moves. Valentine felt the song never got the chance it deserved. "It was election time, and it was a gimmick song," he says. "But that song had a hook. As a gimmick song, if it had been better timed, had a better marketing push, if it didn't come up against election deadlines, that's the kind of song that would have gotten picked up in areas of the country where Joe never played. "I didn't want Joe to be a gimmick, but I did see it as a way to get an audience," Valentine adds. "If Joe did a gimmick song, and it got airplay, Joe's personality would endear him to the people that appreciate a gimmick song during that short window of time." But times were changing. The 1984 election came and went, New Wave had taken over and there was little call for a guy in denim with a moustache and feathered haircut who sounded like Kenny Loggins. Record executives didn't know what to do with him. The big break turned into a big crossroads. His original songs weren't catching on, but his cover-song act still drew lines out the door, and his corporate gigs were starting to pick up. He had a wife and a new daughter already; Sharino took the safe bet and stuck close to home. "I have no regrets, because I'm happy doing what I'm doing," Sharino says. "I was able to raise my kids without being on the road. There's something to be said about sleeping in your own bed. And there's the longevity. The first demo tapes I recorded were in 1975-1976. Who made it big then that's still popular now? Elton John did in 1970, and he's still around. But most of those people are dinosaurs, down-and-goners. I'd rather have the longevity and not be a has-been." Valentine had a scheme of packaging Sharino to Vegas as a more populist version of Wayne Newton. It entailed Joe being away from home eight or more weeks out of the year, playing Vegas showrooms. Joe--and his audience--wasn't ready for it. "Joe had reached a comfort zone," says Valentine. "Joe set his own limitations. He had reached a level of success that nobody had ever done in the niche he was playing in. He was making more than four or five times what any other band was doing playing the same nightclubs on the same days. And people wanted to keep him there." SemiLegendary Sharino closed out the '80s the way he began, packing the local clubs and making decent money. Then Sharino accepted jobs that may make "real musicians" puke. In 1989, Sharino was asked to help write jingles based on slogans that the companies provided. As the prune fields sprouted silicon chips, one gig led to another, and Joe fattened his portfolio, singing about meeting sales goals and producing faster semiconductors. "We started doing jingles; mostly we did in-house stuff for corporations," Sharino says. "GE had a meeting for 2,000 salespeople in the Bahamas. The theme of their conference was 'Catch the Spirit.' So we wrote a song called 'Catch the Spirit.' Corporations all want theme songs for their new product or to motivate the sales force [and] thank the marketing department who kicked butt this year. So we'd write and record them." Also in his repertoire is the "corporate music video," where Sharino records a song based on a slogan and then, using his college filmmaking background, makes a music video that stars the CEO, president and vice president lip-syncing and pretending to play the guitar, the sax, the keyboards and the drums. He's done 25 of these eye-rolling monstrosities. Hey, Joe, aren't musicians supposed to be above these things? No way, he says. He's never taken his career that seriously. And if you call him a sellout, prepare for a taste of his competitive nature. "If your band is playing at one end of the street--you who are calling us a sellout and doing your own songs," he says, sharpening his gaze, "and we're playing the other end of the street, and there's 2,000 people, who's going to have the bigger crowd at the end of the night? And what's wrong with that? Our shows are all sold out, so maybe we have sold out." But Joe knows the score. One day Joe Sharino found himself on the field of Candlestick Park, standing next to Huey Lewis and Seal. Joe remembers the moment well. "They were looking at me, thinking, 'Who the heck is this guy?' and I'm thinking, "Don't you know me? I wrote 'Catch the Spirit' for GE?'" And he laughs.

Any Requests? The Sharino Band doesn't do the "Macarena." Motion Man On this night, Sharino is set to headline a fireworks extravaganza on the beach at Seacliff, near Santa Cruz. The coastline is smacked with fog. About 20,000 people were expected, but it looks like only a third of them braved the elements. It doesn't deter the headliner and his minions, who are keeping warm by twisting in the sand. Joe goes through his usual hit list, leaning heavily on "Play That Funky Music" and "Get Down Tonight" to get the booties shaking. The confetti cannon causes another uproar on "Footloose." An encore is called, and he gets the crowd singing the "ahhhh" part in "Twist and Shout" and then slams the door shut with "I Saw Her Standing There." He exits to roaring applause. On the Seacliff pier, the fireworks show has started. Clouds of fog are suffused with eerie colors to the prerecorded tape of "Get the Party Started" and other contemporary pop hits. Behind the stage, Joe and his wife, Sheri, are enjoying themselves. New fans come by and offer cautious praise; veteran fans greet Joe like an old friend. He invites them all to his next show, a four-waller across the water at the Coconut Grove. Joe leans over and gives the result. "I'd score it 35-25," he says. "We didn't kill--a lot of people stayed home because of the fog. But everyone enjoyed themselves, and that's what matters most. So we still won." This wasn't the way it was scripted. Joe Sharino was supposed to be an international star, not shilling for the Man, far above playing weddings and corporate events, and never, ever playing second fiddle to a fireworks show. But guess what, he's not ruling out a comeback. Joe's currently writing country songs and shooting for a publishing deal. He wants to break into Nashville and pull a Diane Warren--writing songs that up-and-coming singers will like and turn into hits. Until that time comes, Sharino is content performing with his band and sleeping in his own bed. Playing nothing but covers affords Sharino the dual gifts of timelessness and longevity. The Joe Sharino of 2002 is the exact same one who toiled in clubs during the '70s and '80s. His fans know exactly what they're going to get, and Joe Sharino is only happy to give it to them. When I ask if the Sharino of 19 would approve of the Sharino of 48, the question makes him pause, as if a different life path as a superstar suddenly presented itself and distracted his concentration. He steps away from the Grammy podium, washes the applause from his ears and returns to the conversation. He begins his thought slowly and carefully. "The Joe Sharino of 19 would have thought that Joe by now would be touring, had five hit albums, hits on radio, a TV show and made the big time," he says. "From The Ed Sullivan Show, 9 years old forward, that's what I wanted to happen, but I knew it was a long shot. I don't think the 19-year-old Joe would be disappointed in the 48-year-old Joe, because I've got a wonderful family, [and] financially I'm doing well. And I'm still playing music and having fun. That's the bottom line."

The Joe Sharino Band appears Dec. 7 at the World's Largest Small Office Party at the San Jose McEnery Convention Center. Tickets are $40, and reservations are available by calling 408.277.3897. The band also appears at the Cocoanut Grove on Dec. 30 and at the Westin Hotel in Santa Clara on Dec. 31. For more information, visit Sharino's website: www.jsband.com.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the October 31-November 6, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

Left of Center Joe Sharino is right-handed at everything except guitar playing.

Left of Center Joe Sharino is right-handed at everything except guitar playing.

Burning Love: An early promotional shot circa 1975. During the '70s, Joe Sharino had standing-room-only audiences at Campbell clubs like the Parlor.

Burning Love: An early promotional shot circa 1975. During the '70s, Joe Sharino had standing-room-only audiences at Campbell clubs like the Parlor.