![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

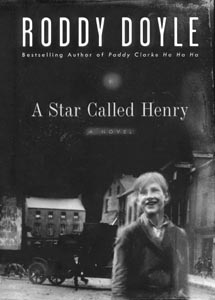

A Star Called Henry By Roddy Doyle Viking; 344 pages; $23.95 cloth A Beautiful Terror Roddy Doyle's street-smart Irish killing machine doesn't give a 'shite'--but readers will

By Allen Barra WOODY ALLEN was probably right when he said that comedy sits at the children's table--at least that's what most critics seem to believe. In Roddy Doyle's case, critical acclaim lagged not only because he wrote terrific comic novels--The Commitments, The Snapper and The Van--but also because those acclaimed novels were made into successful movies. And those were his first three! How deep can a writer be who conquers so easily? With Paddy Clarke Ha Ha Ha, he invoked the routine terror and joys of a 10-year-old boy so exhilaratingly that Doyle began to be overheard at the adults' table. With The Woman Who Walked Into Doors (1996), a terrifying tale of a battered housewife, Doyle pulled up a chair. Now, with A Star Called Henry, the story of a Dublin street urchin who grows up to be a chillingly efficient I.R.A. killer, Doyle is on the verge of having a table all to himself. Doyle's new protagonist is Henry Smart--as in street-smart--the son of a hideously congenial one-legged thug who murders by splitting skulls with a detachable wooden leg. Named by his mom for an older brother who died at birth, Henry grows up amid circumstances so wretched as to make Frank McCourt's childhood seem like Laura Ingalls Wilder's. "I was 8," he tells us, "and surviving. I'd lived three years in the streets and under boxes, in hallways and on wasteland. I'd slept in the weeds and under snow. I had Victor [his younger brother], my father's leg and nothing else. I was bright but illiterate--strapping but always sick. I was handsome and filthy and bursting out of my rags. And I was surviving. [But] it wasn't enough. I was itching for more." Henry seems destined to follow his father's path until he gets caught up with politicals and is trained to kill for a purpose. At first, Henry cares nothing for the politics of killing: "Home Rule ... meant nothing to us who had no homes." Later, he confesses, "I didn't give a shite about Ireland." Soon, though, the war fills the moral vacuum inside of him and, to paraphrase Yeats, a beautiful terror is born. Henry becomes a virtual killing machine: "I shot and killed all that I had been denied, all the commerce and snobbery, that had been mocking me and other hundreds of thousands. ..." Henry is the id of the evolution, an uncontrollable force set in motion by the conditions that shaped the conflict. He escapes from the executions that follow the Easter 1916 uprising and just misses being included in the famous photo of Michael Collins and other leading rebels: "If Hanratty had moved his camera just a bit to the right, just a fraction of a bit, I'd have been in. You'd know my face, you'd know who I was." Henry emerges a year later to find that ballads have been written about him--he has become a folk hero. James Joyce liked to boast that if Dublin were destroyed it could be reconstructed, brick by brick, from the pages of Ulysses. Maybe, but Roddy Doyle would have to be consulted for the seamy underside--the sewers, the back alleys and the docks, the smithy that forges Henry's soul, a soul he seems to find near the novel's end. Avenging his father's death, Doyle realizes, "I wasn't angry any more. I was just murdering. I could have stopped." With a sense of guilty horror we are forced to admit that we don't want him to. [ San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 4-10, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. MetroActive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.