![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

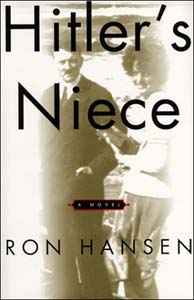

Hitler's Niece By Ron Hansen HarperCollins; 310 pages; $25 cloth A Human Hitler? In 'Hitler's Niece,' the terrible leader of the Third Reich is just a man--however dysfunctional

By Rob Pratt EVEN 65 YEARS later, debate rages over how a middling Austrian with virtually no prospects for making a dent in the world could rise in the span of 30 years to tower over the 20th century, dominating not just Germany but, in a way, much of the world long past his ignoble death. Telling details get left out of most of the theories so far put forward about the peculiar confluence of Adolph Hitler's personal qualities and the larger social and political workings that allowed him to symbolize the height of totalitarianism (even though Josef Stalin reigned considerably longer, and the Soviet Union labored under the Boss' gruesome machine well after his death). A gifted speaker and a leader of the post-World War I National Socialist movement in Germany, Hitler nonetheless had to have something more than a feel for political ideas that would play among the nation's growing disaffected classes to sway millions with his hateful ideas. Though he could thunder for three hours once started, Hitler obviously built most of the Nazi juggernaut while off the podium, face-to-face, whether in day-in-day-out plotting with lieutenants or up-close-and-personal encounters with the public. In Hitler's Niece, author Ron Hansen (a Santa Clara University teacher who with previous novels The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford and Desperadoes seems to have found a niche in fictionalized chronicles of criminal outsiders) presents a vivid and startling novelized account of Hitler's rise to power, making a compelling case for many of the nuances of Hitler's character now lost to the historical record that allowed him to manipulate the people around him and bend a nation's will to his own. In the end, the novel is brutal with an almost ambivalent assessment. Just as Hannah Arendt concluded that Final Solution implementer Adolph Eichmann was neither monster nor evil genius but instead merely emblematic of the workaday "banality of evil," Hansen paints Hitler, perhaps most frighteningly, as only human. The focal point of the story, however, is Geli Raubel, the real-life daughter of Hitler's widowed half-sister, and it's Hansen's characterization of Geli as a bright, charming and skeptical observer both privy to the inner dynamics of the Nazi leadership and entirely disinterested that drives the story. Previous insider accounts like Albert Speer's Inside the Third Reich have to be taken suspiciously, as their authors may have hidden (or, in Speer's case, obvious) intentions of gaining absolution for their part in the Nazi terror. The figure of Geli, however, carries none of this baggage and frees Hansen to investigate what kind of person Hitler was when he wasn't laying plans for the destruction of the Weimar Republic and all of Europe. Opening with Geli's christening, Hansen introduces a young Adolf as quirky and difficult but devoted to his family--particularly to his new niece, 19 years younger than he is. Hansen flashes through Geli's childhood and teen years (which coincide with Hitler's time in the German army during World War I, his early work with the Nazi party, the failed "beer hall" putsch and his eventual imprisonment) to focus on a critical five-year span. It is the time when Hitler invites the 18-year-old Geli to work as housekeeper at Obersaltzberg, his Alpine retreat, until her untimely death in 1931. Officially, her death is recorded as a suicide, but in recent years scholars have argued that she was murdered at Hitler's hand--and this is Hansen's take. It is also the time when Hitler and the Nazi party moved from the fringes of German political life to become a dominating mass movement, culminating two years after the close of the novel with Hitler's election as chancellor. Seen through Geli's eyes, Hitler has genuine charms. Her big-shot uncle is lavish with gifts and attentions even if he has some strange ideas. Soon Hitler's jealousy comes between Geli and a love interest in Emil Maurice, his chauffeur--and, for that matter, any other suitor who shows an interest in his poised, fetching young niece. It is here that Hitler's gross dysfunction becomes apparent. He attempts to control Geli. His mood swings from furious to despairing over her willingness or unwillingness to abide his ever-creepier whims. And as Geli learns of these things in her personal relationship with her uncle, she starts to see how Hitler's paranoia is taking over his Nazi comrades. Eventually forced to become his lover, Geli turns on Hitler and seals her demise. As finely wrought as Geli and Hitler are, though, Hansen otherwise populates Hitler's Niece with two-dimensional characters. Alfred Rosenberg is monomaniacal and dogged by bad breath. Rudolph Hess is jumpy and neurotic. Hermann Goering is fatuous, drugged and incoherent. No doubt the confines of the main story about Geli and Hitler and a well-meaning desire to avoid turning a comfortable read into a tedious tome demanded that Hansen resort to derivative stereotypes of some characters. Hansen does have considerable skill with characterization--even sketches of leading Nazi figures like Joseph Goebbels tell much about what drove them both personally and politically. But if he had loosed his shrewd powers of observation on other telling figures, Hansen might have developed a narrative that added a new wrinkle not just to our understanding of Hitler and Geli's ultimately troubled relationship but also to the larger dysfunctional social dynamic that founded the Third Reich. [ San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 4-10, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. MetroActive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.