![[MetroActive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

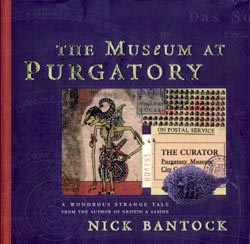

The Museum at Purgatory Nick Bantock HarperCollins; 113 pages; $25 cloth Emotional Baggage Nick Bantock takes readers on a richly visual tour of 10 imaginary collections in 'The Museum at Purgatory' By Heather Zimmerman THE CONCEPT of emotional baggage gets a literal interpretation in Nick Bantock's new book, The Museum at Purgatory. Bantock, the artist/author best known for his sumptuously illustrated epistolaries in the Griffin & Sabine trilogy, turns his exotic imagination to an intriguing vision of a secular afterlife, where, at least as far as Purgatory, you can take it with you--a few things, anyway. Bantock's Purgatory hardly matches the religious version of a souls' holding area only marginally better than hell. Although this Purgatory does exist between the earthly world and the true afterlife, it's as a kind of serene, nonjudgmental city where the dead can decide for themselves where to head next: the Utopian states, among them Avalon, Nirvana and Eden, or the Dystopian states, which include Pandemonium, Styx and Hell. Purgatory's museum houses items that have accompanied some uncertain souls to Purgatory to help them decide their destinations. These items are collections of life-defining objects that the dead gathered throughout their lives in their studies, hobbies, work or obsessions. In The Museum at Purgatory, Bantock has once again adroitly used his talent for making a fantastical fictional artifact seem absolutely real. Curator Non, an amnesiac, narrates a heavily illustrated tour of 10 collections that have personal resonance for him and later shares his own story: having arrived in Purgatory with no memory, his life-defining collection is made up of the obsessions of these other collectors. The book works on many levels; the most obvious and practical is that Bantock has found a clever showcase for some of his three-dimensional works that don't lend themselves to publication as well as the collages that made the Griffin & Sabine series so popular. Purely an art book, with its photographs of unusual sculpture, both beautiful and slightly grotesque, and fanciful, bizarre objects (where, other than in a Bantock book, can you find bottled angel essence or psychically charged Persian carpets?), The Museum at Purgatory will look great on the coffee table. NOT QUITE SO ASTUTE as his illustrations, Bantock's text relies heavily on amateur psychology in the collectors' case histories, as told by the curator, which accompany samples from their collections: a mummy-gathering archaeologist dreaded the future and thus stayed focused on the past; a board-game designer satisfied his competitive nature with his creations. When at last we learn something of the Curator himself, the knowledge proves to be a little disappointing, a little too pedestrian, perhaps, compared to the fascinating assortment of people who interested him. Fortunately, it is not just Curator Non's personality that gradually takes shape in these collections. There seems to be a thinly veiled hint of Bantock himself in some of these characters, most whimsically in Matrice Levant, a maker of spinning tops who created an elaborate fake history for his creations that people accepted as reality. One of Levant's tops supposedly originates from the Sicmon Islands, the fictional South Seas home of Sabine in the Griffin & Sabine trilogy. Another collector devotes his life to studying the link between words and images, trying to understand their connection. Although this collector tortures himself over whether or not his scholarship succeeded, Bantock's own soul might be free of such worries. The Museum at Purgatory is a beautiful, imaginative book that, in both visual appeal and content, demonstrates the emotion with which we can imbue objects, and, more specifically, art--whether it's simple admiration or disgust at outward appearance, or a deeper, more personal resonance. With The Museum at Purgatory, Bantock offers something of a visual catalog of the nature of art itself--it means different things to everyone, but it always means something. [ San Jose | MetroActive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 4-10, 1999 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 1999 Metro Publishing Inc. MetroActive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.