Citizen Ziggy

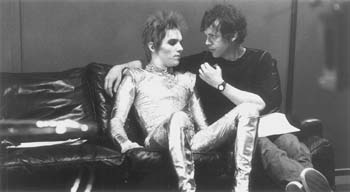

All That Glitters: Jonathan Rhys-Meyers (left) gets some tips on impersonating David Bowie from director Todd Haynes.

In 'Velvet Goldmine,' Todd Haynes mourns the glitter-rock utopia once promised by David Bowie and Iggy Pop

WERE OSCAR WILDE and David Bowie aliens from outer space? At the beginning of Todd Haynes' new film, Velvet Goldmine, a flying saucer drops the infant Wilde, carrying a magic amulet with him, on the doorstep of his parents. Many years later, the jewel is found by the little boy who is to become a fictionalized version of David Bowie (yes, yes, I know, he's fictionalized himself enough already).

In Velvet Goldmine, a rock star named Brian Slade (Jonathan Rhys-Meyers) is the Bowie of his dimension, complete with flamingo-tinged hair and a Ziggy Stardust-like alter ego, Maxwell Demon. At the peak of his career in 1974, Slade is shot onstage at London's Hammersmith Odeon, but what at first looks like an assassination turns out to be a neurotic publicity stunt.

On the 10th anniversary of Slade's "shooting," we visit a gray, tightly run New York under the regime of a Reagan-like President Reynolds. A reporter named Arthur Stuart (Christian Bale) has been assigned to find the missing rock god.

It's a painful job for Stuart. The reporter grew up gay in the suburbs and was saved from self-hatred and self- destruction by Slade's gender-blur glitter rock; the faked assassination was a personal betrayal of his trust. At this point, you may sense where Haynes has gone wrong--who can revisit the music of his youth without at least some pleasure?

Stuart, however, is a sad, mumbling shoegazer who'd probably be better off listening to Natalie Merchant. Still, Arthur eventually solves the mystery of Slade's disappearance and is himself made whole by an encounter with Slade's old friend, collaborator and lover Curt Wild (Ewan McGregor).

HAYNES IS A postmodern pastiche artist. His early film He Was Once... parodied claymation Davy and Goliath cartoons. The underground Superstar (using Barbie and Ken dolls) was a show-biz bio of Karen Carpenter. B-grade '50s science fiction movies gave structure to the smart AIDS allegory, Poison. And Safe, Haynes' best film, was an inside-out version of a television disease-of-the-week movie.

As a mark of his ambition for Velvet Goldmine, Haynes has used Citizen Kane as the model for his narrative. Stuart is given his assignment in a newsroom with a movie screen, just as in the beginning of Orson Welles' classic. Stuart's sources include Cecil (Michael Feast), Slade's ex-business manager--a character very much like Joseph Cotton's Jed Leland in Kane. Slade's ex-wife, Mandy (Toni Collette), is interviewed by Arthur in a closed nightclub during a thunderstorm, as was the Susan Alexander character in Kane.

Velvet Goldmine is also inspired by the ideas of the Fox Mulder of rock critics: Greil Marcus. One of the exhibits in the search for Slade is a record album titled Lipstick Traces, which is also the title of a Marcus book. Like Marcus, Haynes tries to search out the links between pop music and higher art forms--hence the guest appearance by Wilde in a story about the glitter-rock era. (Quotes from Wilde and philosopher Norman O. Brown stud the film.)

And like Marcus, Haynes stares so closely at the fragments of a scene that he loses the big picture of what was going on elsewhere. London pop music has always been a blend of so many signals that even the most sympathetic, studious American listener is going to miss clues--everything from slang to the names of neighborhoods. Haynes, an American, suffers the same problems as a European making a movie saluting American pop culture.

Haynes does acknowledges some of the musicians who pioneered gender-blur rock, such as Little Richard. Still, it's overstating the case to argue that glitter was ever anything more than a marginal outcropping of British rock in the early 1970s, back when men first started to perform in torn lingerie and lipstick.

Who can blame Haynes for romanticizing? Like all Americans entranced by British rock music--who spent hours scrutinizing the cryptic album covers--Haynes has deluded himself into thinking that England was a country where everyone would understand your jokes, wimps were welcome and all sexual possibilities were accepted.

Of course, the reality was something different. The glitter scene wasn't democratic, as punk was--snobbery ran wild. And as I recall it, more and more sobering recollections pop up: Oh, yes, them were great bloody days. Dried egg white fixing glitter to the eyelids, shedding razor-sharp bits into the corneas; too-tight French-cut T-shirts garroting your armpits; badly engineered, hulking platform wedgies held on by tiny little ribbons.

A typical memory of the time is propping up a Qualuuded date as she limps back on her twisted ankle to the RTD bus stop or escaping a disco where all the Eurotrash snubbed us for being suburban pratts. Which we were.

IT WAS TRULY FUN music, however, and Velvet Goldmine is certainly not a fun movie. The baleful Christian Bale sets the tone for this study of melodramatic, facetious music. Velvet Goldmine is a dirge for all of those polysexual dreams running down the drain like so much periwinkle-colored hair dye.

Unfortunately, the film is most coherent when it follows the well-worn wheel ruts of the standard show-biz biography: star gets swelled head, star fucks himself up on drugs, star finally honks off his loyal wife.

The center of Velvet Goldmine is a bisexual love triangle modeled on the relationship of David Bowie and Iggy Pop. Thus, Slade's wife, Mandy (played by Toni Collette with the jittery, needy, scary mannerisms of Liza Minnelli), must be based on Angie Bowie. The ex-Mrs. David Bowie was on the chat-show circuit a few years back, telling everyone who would listen about the day she discovered her husband and Mick Jagger in bed together, and that anecdote (with Mick changed into Iggy) turns up in Velvet Goldmine. Curt Wild is a fictionalized Iggy to match the fantasy Bowie, Slade.

As Slade, Rhys-Meyer is no worse than the since-forgotten pseudo Bowieoids of that time, such as Jobriath or Leo Sayre. But fictionalizing Iggy Pop--now you've insulted the Sultan! McGregor, the Scottish actor best known from Trainspotting, commits the common mistake of people covering Iggy Pop songs: he tries to make the vocals musical.

Those magnificent Aborigine death shouts that Iggy calls singing don't benefit from added melody. McGregor's preposterous impersonation of the sui-generis rock star performing Iggy's songs "TV Eye" and "Gimme Danger" is insufferable. This isn't a performance, this is karaoke.

For whatever legal reason, Haynes wasn't allowed to use Bowie's music. In Surviving Picasso and Love Is the Devil, the filmmakers had no legal access to real Picasso and Francis Bacon paintings and had to create imitation ones. Similarly Velvet Goldmine's soundtrack contains Bowie and Iggy pastiches created by Ron Ashton, ex of Iggy Pop's band the Stooges.

The rest of the film's soundtrack consists mostly of pieces by Roxy Music and solo work by Roxy Music's gifted keyboardist, Brian Eno. Roxy Music was interesting for the tension between the crooning of lead singer Brian Ferry and the icy, futuristic keyboard playing of Eno. Although the Roxies dressed up in Halloween-came-early outfits for their publicity photos, it's less clear that gender blur interested them.

The group's album covers featured lingerie photos of supermodels like Jerry Hall, who later married Ferry. One feels dislocated hearing Roxy Music's "2HB," a song about Ferry's manly admiration for Humphrey Bogart, sung by Velvet Goldmine's Brian Slade, covered with more glitter than Dorothy's pumps and more feathers that a pheasant.

Haynes makes clever use of the Eno song "Dead Finks Don't Talk" as accompaniment for scenes of Stuart unearthing Slade's betrayal of his wife and fans. Still, Eno was a collaborator in the changing of Bowie's stage persona from Diamond Dog glitter boy to bloodless white-clad aristocrat, and the two worked together on Bowie's Low and Heroes albums. In Haynes' view, Bowie's change of style betrayed glitter rock and the bisexuality it championed. But since Eno was Bowie's accomplice in killing off glitter, why celebrate Eno's brainy, cold-blooded pop music?

This may be quibbling. All of those varied musical styles and substyles are moldering in a common grave today, unvisited by any but us cultural sextons. But this difference between Bowie and Roxy Music is notable; and what Haynes has done is the same as making a movie about Nirvana using Soundgarden's music. (And you know there's going to be a Nirvana movie someday, as sure as needles are sharp.)

Velvet Goldmine is an inchoate picture, all about the filmmaker's deeply personal reactions to glitter rock. It's always fascinating to watch an artist work out his obsessions. But in losing the music of Bowie, Haynes couldn't find a worthwhile substitute; it's like an Elvis movie without Elvis.

True, imitation Bowies were ridiculous, but somehow the real one wasn't. Space alienism? Who knows. But like opera, rock almost always looks bad in close-up on a movie screen. Velvet Goldmine will join the rock fantasias that seem like betrayal of the personal daydreams of most fans, about what the meanings of songs were--like Ken Russell's Tommy or Franc Roddam's Quadrophenia. This film fails its ambitions; it aspires to be David Bowie, and it's more like Gary Numan.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![]()

Peter Mountain

Velvet Goldmine (R; 117 min.), directed and written by Todd Haynes, photographed by Maryse Alberti and starring Ewan McGregor, Jonathan Rhys-Meyers and Toni Collette.

From the November 5-11, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)