![[Metroactive Stage]](/stage/gifs/stage468.gif)

[ Stage Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

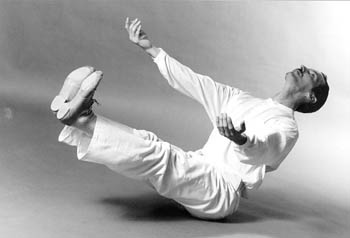

Portrait of the Artist as a Young Dancer: Michael Howerton portrays artist Marc Chagall in Margaret Wingrove's 'The Art of Dreams.' Time, Lines and Dreams Margaret Wingrove explores the light and dark sides of the creative impulse in newest pieces By Marianne Messina WITH HER creativity on overdrive, choreographer Margaret Wingrove and her dance company presented a program of three premieres last weekend at San Jose Stage, all researched and composed over the short span of summer. The current Chagall exhibit in San Francisco inspired the first piece, The Art of Dreams. "Chagall is a happy artist," Wingrove observes, and as principal dancer Michael Howerton rendered Chagall's puckish visual lines, his frequent smile captured the artist's lightness of spirit. Decked in Karen MacWilliams' outstanding costumes--from the lush red splash of Patricia Perez's Firebird leotard to the replicative costumes of The Fiddler and The Acrobat--the dancers played time and line games with Chagall's static counterparts, projected on a screen behind them. In a way, the second piece, Zelda (a portrayal of Zelda Fitzgerald, F. Scott's psychologically abused wife) forms a sort of Möbius strip continuum with The Art of Dreams. In Wingrove's vision, both Chagall and Zelda Fitzgerald possess--or are possessed by--artistic genius, but whereas Chagall's flows sweetly, Zelda's is bluntly thwarted. Both dances reach climactic intensity around music by Bach. Carol Ann Miller dances Chagall's The Acrobat, and at Saturday's performance, as she contorted herself into union with a hula hoop, she drew whisperings of "beautiful" from all over the house. When Lori Seymour's Zelda dances Bach with similar moves and a picture frame, the frame nearly bisects her, its sharp corners threatening--and what was a loving surrender for the Acrobat becomes a victimization for Zelda. Wingrove's work offers so much food for thought, it seems irreverent to waste words on minor imperfections--didn't Jekyns Pelaez's lifts and assists in the Firebird and Prince sequence seem just a bit strained? Didn't the costumes in A Sacred Path have that polyester cling? And what, in Miller's hoop dance, as she danced angular power and discipline to Bach's punctilious, predictable rhythm, was that arhythmical clicketyclacking? (Can't you buy a hula hoop without beans in it these days?) But Miller's magnetic performance forces meaning from the loose, random noise. Like the ruthlessness of geometric shape against the sloppy roundness of human form--or the improbability of imposing static design on something fleet--the physics of beans in motion inside a hula hoop simply ignore human conceptualization. In the performance, they foreshadow the way Chagall's life, picture-perfect by human design, was dealt the random disruption of his wife's untimely death. The Wingrove Company's program offered many of those perfect instants that linger. For example, Patricia Perez breathes life into the feathered and combed iterations of Chagall's Firebird with her tiny but frantic finger flutterings. And in The Sacred Path, Pelaez and Laura Sefchovich approach each other, slow and dazed, exchange a flicker of recognition, of possible embrace, then drop all recognition and pass each other by--an impeccable fraction of a second, haunting in its sense of desolation. Wingrove ends The Sacred Path ensemble piece by banding the five lone wanderers together to form a human wave, and in her characteristic way, she leaves us inspired by a vision in which our essential human connectedness prevails.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the November 6-12, 2003 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.