Robert Scheer

Music Man: Victor Santos' teaches a first-grade music class focusing on Spanish and Mexican music.

Ron Unz says he launched his crusade against bilingual education to help immigrants, even though it would destroy exemplary local programs

By Lauren Barack

CECILIA BARRIE walks across the grounds at River Glen Elementary. It's recess, and children dart across the blacktop, playing ball while chasing each other. Barrie, 47, a petite woman with blond hair and wearing a bright yellow pantsuit, cuts a striking figure. She's the school principal, and the children react immediately when they see her.

"Hola, Maestra Barrie," shouts a young Latina girl in pigtails. She starts to rush toward Barrie, who smiles but holds up her hand as if to say "not now." A young boy shoves his friend forward and says, "Maestra Barrie, he's a dork." She keeps walking until she's a comfortable distance away and laughs. "Did he really say that?" she asks as she walks into bungalow 15, one of four kindergarten classes at the school.

Inside, six students are coloring pictures with a teacher, who asks them in Spanish to put the drawings away in plastic envelopes. "Like this?" asks one little girl, in English. "Si," replies her teacher and repeats her request again in Spanish. The children follow her instructions, and the little girl smiles and claps her hands.

Most of the students at Willow Glen's River Glen Elementary have no idea that their Spanish teachers know English. That's the way the teachers want it. Through immersion in the language, native English-speaking students become fluent in Spanish by the time they leave school in the seventh grade. Spanish-speakers learn English without being sent to slow-tracked ESL classes and without losing their native language.

Ron Unz has never seen the inside of bungalow 15 nor walked the school grounds here, where children banter in both Spanish and English. A 36-year-old Palo Alto businessman and onetime candidate for governor, Unz is the author of the so-called English for the Children initiative. If approved by California voters in 1998, the initiative would prohibit bilingual education in public schools.

In Unz's world, non-English-speaking students belong in segregated remedial classes where English is spoken, and English only. Unz says he's always been opposed to bilingual education and has spent the past year campaigning to put an end to programs at schools like River Glen.

Unz doesn't like to answer questions directly and instead replies with theories and ideas about possibilities. He occasionally contradicts himself.

"It doesn't make sense for there to be bilingual ballots," he says emphatically during one of our interviews. "They should be in English. That's the official language of the state." He pauses. "But then it's not really a significant issue."

Unz doesn't waffle about his belief that it's better for immigrant students to learn in a crash-course approach and to be segregated from mainstream classes until they know English. "They're segregated in bilingual classes now, aren't they?" he asks rhetorically.

In his mind, learning English is an important part of fulfilling the American dream. It's a patriotic duty. "It's an important part of assimilating into society, and it's important to continue that tradition, especially for immigrants."

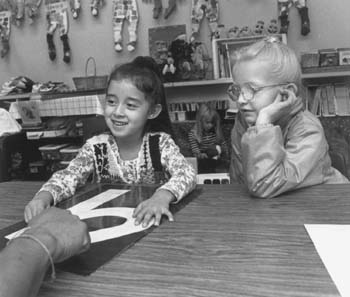

Robert Scheer

Math Communication: Rosalyn Grijalva, left and Erin Wilcox, both kindergartners at River Glen Elementary, learn their numbers in Spanish.

Strike Tres

UNZ'S SCHEDULE is packed. He appears in forums, makes speeches, holds meetings and gives interviews on his cell phone on his way to the airport--so many that he doesn't remember one reporter from the next. He's driven to see his initiative succeed, though that's occasionally hard to decipher beneath his evenly paced, singsong voice.

Unz credits two articles in the Los Angeles Times for spurring his recent interest in ending bilingual education. Latino parents, angry that their children were in bilingual classes and not learning English, began boycotting an elementary school in Los Angeles in early 1996, he says. That spring, Unz met with the parents and then drafted his initiative. "The kids aren't learning to read and write English," he says. "And if you can't speak English, you probably can't get a job. And those people contribute to other problems."

Unz, who says his grandparents emigrated from "Russia, Poland and other Slavic countries," says he feels "an affinity for immigrants." He was very strongly opposed to Proposition 187 ("I'm the one that got Kemp and Bennett against it," he brags) but in favor of Proposition 209. He says he made his run for governor two years ago because he was "very angry at Wilson about his immigrant-bashing."

But Barrie, who is in the trenches, calls his solution to end bilingual education the "third strike" against immigrants--even though she believes that traditional bilingual education is failing children.

More than a quarter of the students that enrolled in San Jose schools last year--8,989 children--either could not understand English or had a limited grasp. More than 90 percent spoke Spanish, Vietnamese and Portuguese, and of those, 4,154 enrolled in bilingual programs teaching the children in their native language. The rest spoke an assortment of 38 or so languages, including Kurdish, Serbo-Croatian and Samoan, or didn't have bilingual classes at their schools and were taught in ESL classes. In ESL, or English as a Second Language, students are taught English--but without help in their own language.

Unz' initiative would force all non-English-speaking students, like the 367 enrolled in bilingual classes at River Glen, back into sheltered English immersion classes, such as ESL. The initiative would force schools to segregate the students by their language abilities, but without regard to grade level or native language. The instruction would last a maximum of one year, and the students would then re-enter regular classes.

"It's the 'sink-or-swim' approach," Barrie says. "At best they learn some English. At worst they learn nothing or forget their original language."

Robert Scheer

Minds over Manner: Seventh-graders at the bilingual River Glen Elementary work on a diagram comparing the Romans and Byzantines. From left, Megan Beaver, Adrianna Hernandez, Jamie Murphy and Jose Luna.

Losing a Language

THE BILINGUAL PROGRAM at River Glen teaches children English and Spanish by instructing them in both languages during the day. The students start the program at kindergarten and by the end of seventh grade are fluent in two languages. It takes more than the year suggested by Unz, but Barrie believes the payoff is worth it.

"It's extremely important for Latino children to learn English," she says, "but it doesn't have to be at a cost to their native language."

Many Latino parents agree with Barrie's point of view. Vicky Ortundo emigrated with her family from Argentina six years ago. She was placed in an ESL class at Carson Elementary School. But in the fourth grade her parents enrolled her at River Glen, concerned that she wasn't learning English well enough and that she was losing her native Spanish.

"I kind of had an accent," says the 12-year-old with dark-rimmed eyes and long chestnut hair, who now speaks both languages fluently. "I love her accent," says 12-year-old Jamie Murphy, his face flushed.

Jamie, a native English-speaker born in San Jose, enrolled at River Glen in kindergarten. Now in the seventh grade, he can speak fluent Spanish and often translates for his mother at work or when she's trying to talk with Jamie's Spanish grandfather. "It's cool," he says. "They should have more programs like this, not take them away."

Unz says that would never happen. The software entrepreneur still feels the same as he did when running for governor. He's not against immigrants, he says, and points out a clause in his initiative that allows parents to put their children in bilingual classes if they meet certain requirements. Unz believes that should be enough to reassure concerned parents, who are part of what he calls the "bilingual establishment."

"It doesn't outlaw bilingual education," Unz says.

Inside a conference room at River Glen, Marilyn Dion points to the cover page of Unz' initiative. "Then what's this?" she asks, pointing to a line that reads, "With your help, we can end bilingual education in California by June 1998."

With two children at River Glen, Dion is concerned about the fate of the school. Along with several parents of children at River Glen, she is looking into a state bill drafted by Sen. Dede Alpert and Assemblyman Brooks Firestone that would allow local districts to decide if they want bilingual programs.

Robert Scheer

Principal of the Matter: Cecilia Barrie, principal of River Glen Elementary (with Ariel Casillas, left and Jazmin Lavigne), says Unz's English-only initiative will be the third strike for immigrants.

Talking Money

AS OF JUNE, Unz had reported spending $60,000 of his own money on the initiative, though he says the amount is now more than $150,000. Another $50,000 in donations came from two Florida contributors. When asked why Florida residents are contributing to a California initiative, Unz says, "It's an issue that will affect the whole country. Once bilingual education is gone in California, I think it will be gone across the country in a year or two."

Help closer to home is also on the way. The state's Republican Party voted to put the initiative in its platform at the annual convention this October.

Meanwhile, River Glen Elementary is still planning to add eighth-grade classes next year. Bulldozers strip dirt from the grounds for a new staff parking lot and classrooms, near a field where Vicky, Jamie and other students stretch during a physical education class. As they exercise, they also talk, often in a mixture of Spanish and English, "Spanglish," says Vicky sheepishly. "We're not supposed to," adds 12-year-old Sarai Camberos, Vicky's classmate, who also enrolled in River Glen in the fourth grade, with English as her second language.

The students are careful about not speaking the hybrid in class--that can result in a reprimand, their name being written on the board or being sent to Maestra Barrie's office.

Today, there are no names on the classroom board, just Spanish words. "This will help us get jobs one day," says Sarai, who is thinking about becoming a lawyer. Vicky doesn't know what she wants to be yet, but she agrees with her friend about the advantages of speaking more than one language. Says Vicky before she turns to join her friends in conversation: "It's a great privilege to be bilingual."

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)