The Boys in the Band: Euphemisms have no place in the gleefully explicit world of Pansy Division.

Punk is dead, but its rage and anarchistic joy live on in lesbian and gay bands like Pansy Division, Team Dresch and Tribe 8

By Gina Arnold

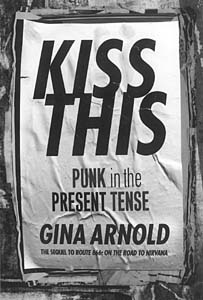

In her new book, Kiss This: Punk in the Present Tense (St. Martin's Griffin; $11.95 paper), Gina Arnold went looking for the remnants of a movement that had sold out, grown old and died off. Along the way, she discovered the true children of punk who still believe that the music matters more than the money. In this edited excerpt from Kiss This, Arnold explores the fierce independence of openly gay and lesbian rock bands.

THERE ARE PLACES IN this world where irony is inappropriate--places in the past, and places in the heart. One such place is Portland, Ore., where the downtown has no cafés or liquor stores, just a profusion of old-man hotels and steak restaurants called things like Jake's. It looks like a scene from a Depression-era photo, all warehouses and train tracks and evergreen-colored vistas of the Willamette River popping through the gaps between old brick buildings.

Portland is a city whose denizens will never need sunglasses: the air is so perpetually cool and dark there, it would seem like the world's biggest affectation to don them. It is, however, a place where the burning embers of punk rock are being harbored and hoarded in every corner and cornice. Slack and unpretentious, a vision in black and white, Portland bands huddle together over a little pile of coals, warming their hands and drawing strength from the fire. And nowhere is the fire so strong as in the center of Portland's queercore movement.

Greil Marcus once noted that "there is no greater aesthetic thrill than to see minority culture aggressively and triumphantly transform itself into mass culture." Thanks to Nirvana's diffusion of alternarock values throughout the very fabric of the mainstream, the past couple of years has allowed pop-culture mavens to view just such a phenomenon at all-too-close range, and alas, the thrill is gone.

Sure, the economic ramifications of having an indie band like the Offspring all over MTV are inspiring, but where is the rush involved in the sight of Henry Rollins shilling for Macintosh computers, Kim Gordon hawking clothes for über-hip anorectics or Courtney Love on the cover of Vanity Fair?

If you're addicted to being a member of the underground opposition, you now have to look elsewhere for the sense of exhilaration that the sight of minority culture infiltrating the status quo can give, and at the moment, that means looking queerward.

Queercore--a.k.a. homocore, a broad term used to describe punk rock bands formed by out gays and out lesbians whose politically charged music explores aspects of being gay with a defiant mixture of humor and anger--has been cultivating itself for quite a while.

Queercore differs radically from previous forms of gay expression in rock & roll in its extreme sexual explicitness. Songs like Pansy Division's "Ring of Joy" ("It's an orifice of elimination / It's an orifice of self-expression") and Tribe 8's "Neanderthal Dyke" ("I never read Dworkin / I ride a big bike") are, by conventional standards, more than a little offensive.

To queercore acts, utter abrasiveness is part of the solution. "We've been excluded for so long that we have to balance out the imbalances," explains Tribe 8's Lynn Breedlove. "It's like affirmative action; for a while, you have to go to the opposite extremes."

Queercore has been around for some time. But it wasn't until Green Day took a goofball queer band called Pansy Division out on the road with it last fall that the subculture was allowed to peep its little head over the barricades that guard the entrance to mainstream American life--much less even think about making a dent in youth culture.

Subsequently, in its first two days of release, Pansy Division's new LP, Pile Up--actually a collection of B-sides and covers--shipped 7,500 copies, nearly what the band's previous LP, Deflowered, sold in a whole year.

Pansy Division, who had been playing around the Bay Area for about three years (appearing at Streetlight Records in Santa Cruz, Cubberley Auditorium in Palo Alto and the Cactus Club in San Jose), sings punky, poppy songs about, not to mince words, buttfucking. Led by former Outnumbered guitarist Jon Ginoli, Pansy Division's whole trip is a relentless, remorseless, seemingly endless celebration of anal sex.

In some ways, Pansy Division's tuneful repertoire is like one of those really bad jokes that only gets funny on its millionth utterance. Its litany of songs about men with big dicks may be queer in intention, but it is still, after all, a series of songs about men with big dicks, and therein lies its charm: by retaining one of rock & roll's heterosexual constants, it really puts its message across. Kids love it, because it shocks their parents even more than "Cop Killer" or "Gin and Juice." Straights love it because it's ironic and funny. And queers, of course, can consider it a call to arms.

On Pile Up, Pansy Division invigorated an otherwise moribund punk scene with covers of songs by Spinal Tap ("My baby fits me like a flesh tuxedo / I want to sink him with my pink torpedo"), Liz Phair ("Flower") and a particularly seamy version of Johnny Cash's "Jackson," done as a hilarious boy-boy duet with Beat Happening's deep-throated Calvin Johnson. The band even revitalizes Nirvana's "Smells Like Queer [sic] Spirit" by injecting the already unstoppable tune with its own original defiance via lyrics like "bun splitters and rug munchers too / We screw just how we want to screw" and "forget the closet, nevermind."

Lawrence Livermore, owner of Lookout! Records and the man who signed Pansy Division, says that queercore's closest analogy is to '60s activist music. "Back then there were bands who sang overtly about politics--putting politics first--while there were other bands who had similar views about being against the war and pro-pot but didn't make it the focus of their music," he says.

"Nowadays, certain [queer] bands make that a central issue of their art and music," says Livermore.

Subcultural Revolutional

Subcultural Revolutional

QUEERCORE IS not a genre, like grunge, however--it's a subculture. The bands involved may be allied in their goals, but they sound entirely different from one another. Tribe 8, for example--which records for the Alternative Tentacles label--is a loud, fast, and angry punk rock band whose members often pretend to castrate men onstage during performances.

In 1994, Tribe 8 was invited to perform at the prestigious Michigan Womyn's Music Festival, where it challenged mainstream lesbians' preconceptions about punk rock through its performance, and through a workshop it led to help educate those who didn't understand its message.

"They realized they missed out on asking 7 Year Bitch and L7 before they got too big to play," explains Tribe singer Breedlove. "But they know they needed to get a younger generation interested, and that PC lesbian folk music isn't going to do it anymore."

Similarly, many young homosexual men are not particularly enamored of the stereotypical gay man's delight, disco. "I've always felt," Pansy Division's Jon Ginoli comments, "that mainstream gay culture not only didn't include me, it was antagonistic to me. People were like, 'You like rock? You don't like Judy Garland?' "

According to John Gill, author of Queer Noise: Male and Female Homosexuality in Twentieth Century Music (University of Minnesota Press), the recent development of queercore is an appropriate response to the current economic and political climate of America. "The cultural profile of mainstream gay culture is complacent, white, male, upper-middle-class. It has no relation to young people growing up angry and scared in the age of AIDS," explains Gill.

"In the '80s," he adds, "people were not too bothered by gay identity--they were too busy having a party. Hence the popularity of artists like Boy George or Erasure. Queercore shows that there is a new form of anger in society. Young gays are determined not to (a) assimilate and (b) adopt the bourgeois culture they see around them."

Gill also points out that many cutting-edge purveyors of popular music have been perceived as "queer" when first seen by a puzzled mainstream. "I suspect that, early in his career, certain white people called [male] Elvis Presley fans queer."

"In the late '70s, if you were into punk rock," agrees Ginoli, "you got called a faggot anyway, whether you were or not," Ginoli agrees. "That's why homocore has this obvious connection to punk."

Growing up in central Illinois, Ginoli had, in fact, liked such punk bands as the Buzzcocks, the Ramones, the Au Pairs and the Slits. After attending college in Champaign, Ill., he formed a band called the Outnumbered, which released two albums in the mid-'80s. He was, however, the band's only gay member.

"The other guys were really cool with it, but I felt I couldn't sing openly gay lyrics because it wouldn't be fair to them," Ginoli says.

In 1987, the band broke up. "I said, to myself, If I'm ever in a band again, it will be an openly gay band," Ginoli explains. "So I figured I'd never be in a band again."

A few years later, however, having relocated to San Francisco, he saw the Austin-based rock band 2 Nice Girls. "They did this song, 'The Queer Song,' " he recalls. "It was really funny and gutsy and in your face, and I thought, 'Why aren't there any guys doing stuff like this?' "

Inspired, Ginoli went home and wrote four such songs on the spot, which resulted in the formation of Pansy Division. The group soon had a local following and an album (Undressed, 1993) out on the Lookout! label--the same label that released Green Day's first two albums.

After Pansy D's second LP, Deflowered, came out in 1994, Green Day's third LP, Dookie (on Warner Bros.), went platinum, and the band insisted on taking its former labelmates on tour with them.

"The thing about going out with Green Day that was so great," says Ginoli, "was that we got to play to really young and diverse crowds. I always thought I'd only be playing to people like me, in their 20s and 30s, who are disaffected with the gay scene, who wanted to hear something gay that wasn't techno or disco or show tunes."

Tribe 8 agrees. "Here in San Francisco, there is a community of gays, lesbians, queers and punks, all kinds of freaks from all over, and we validate each other every day," says Breedlove. "It's really important for us to get our music out by touring and going to towns where there's not a community like this, to let people know that they aren't excluded, they are included in something, however small, however peripheral."

What are straight people getting out of queer bands? "Don't a lot of people go to reggae shows?" asks Breedlove, rhetorically. "And isn't all reggae music about the white devil?

"It's really important for white people to teach each other about racism and for straight people to teach each other about homophobia," she adds. "That's why some guys like us--because they know that their ilk has caused a lot of problems!"

Marc Geller

On the Attack: Tribe 8 believes that utter abrasiveness onstage is sometimes necessary to make sure that queercore bands are heard loud and clear.

Core of the Matter

FOR BANDS like Pansy Division and Tribe 8, the punk rock roots of the suffix "core" are just as important as the prefix "queer." They are extremely concerned with retaining their credibility, fearing corporate co-option, the punk rock dilemma that recently skewered Green Day.

Some queercore protagonists feel that the media are already exploiting the movement by turning it into a trend that will subsequently be defused and discarded--as they have previously done with riot grrrls, angry women rockers and a few other radical subsets of rock & roll. To "go mainstream" is unpunk--and, apparently, unqueer.

But the incorporation of queer culture into the mainstream is of slightly more political importance than the vaguer ideology of opposition that indierock represented. (After all, indie rockers, the vast majority of whom are white, upper-middle-class, college-educated males, could hardly be called an underclass.)

In light of that fact, it becomes less surprising that this burst of what Yeats would call passionate intensity would come from an all-women band. Not only is the all-guy band sound pretty much all played out, but guys who join bands have everything to gain: the respect of their peers, a girl- (or in Jon Ginoli's case, a boy-) friend, and--in this, the heyday of alternarock co-option--a shot at Sonic Youth-sized superstardom and the concomitant bucks.

Women, however, still have more to risk and almost nothing to gain from joining bands, since bourgeois culture has little to offer them that's worth thinking about. (What? Flowers? Liposuction? A date with Johnny Depp?) Thus, in punk rock, women are still margin walkers--and the band that is simultaneously marginal and potentially commercial-sounding is Portland's Team Dresch.

Less obnoxious in its personal manner than Bikini Kill, less off-putting than Fifth Column or Tribe 8, Team Dresch stands in direct opposition to most all-girl bands in that its members are completely unconflicted about their sexuality, their long-term aims and their music.

More than any all-female band today, Team Dresch (which has performed at the Santa Cruz Vets Hall) rocks out. Its two records, Personal Best and Captain My Captain, have nothing in common with hard-core queercore, with riot grrrl, grunge or even the band members' antecedents. Instead of the boring old rage of the disenfranchised female; the hoarse medusa shouts of Donita, Kat, Kathleen and Courtney, Team Dresch provides a precisely furious but tuneful roar--and passionate but fluttery vocals that sound like Kim Deal if Deal sang songs by Railroad Jerk.

As if that were not enough, Team Dresch's songs have the energy of Biohazard crossed with melodies as hooky as Oasis'; and Captain My Captain opens with a kickass couplet that could lead a generation into battle: "My mom says she loves me / but I don't think she does / 'cos she only loves me when I act just like she does." The rest of the album is equally salient, one long stretch of music that literally redefines the very boundaries of what is punk, while even questioning its very own motives on the songs "Yes I Am Too, But Who Am I Really?" and "Remember Who You Are."

Team Dresch isn't really concerned with assimilation (like L7) or challenging conventions of femininity (like Bikini Kill). Its songs are intensely personal rather than political ("Hate the Christian Right" is an exception). The band is, however, in many ways modeled after Fugazi, both in band dynamics--lead vocals are shared, switched and intertwined by Donna Dresch, Jody Bleyle (a.k.a. Coyote) and, on the earlier record, Personal Best, Kaia Wilson--and also in that it has a policy of playing all-ages shows and aggressively interfering with the audience if the audience gets out of hand. Like Fugazi, the band has the sheer chops to back up its moral dictates. Its contextual idiosyncrasies are merely convenient adjuncts meant to facilitate the main thing: music.

Like Ginoli, Bleyle says she doesn't feel a lot in common with mainstream queer culture. "When I was at Reed, I identified way more with the rockers than I did with the women's-center people," says Bleyle. "I went to one women's-center meeting and I felt totally ... I think what I felt was total gender dysphoria. I felt like a boy who wasn't supposed to be at the women's-center meeting; I felt like a spy who was going to say something wrong or do something wrong and get kicked out."

As for mainstream gay culture, she distrusts it as much as straight punks distrust the corporate version. "These days, everybody has a lifestyle marketed to them--and when it gets more specific, it gets more offensive," she comments. "I mean, we're all getting marketed to, but when you open Out magazine and it's that specific, and the bourbon ads are like so ... embarrassingly homocentric ... the more offensive it is."

Diana Morrow

Dresch for Success: What separates Portland's Team Dresch from other angry women bands--the riot girrls, Hole, whoever--is its sense of humor and courage.

Screwing Your Courage

WHEN PUNK becomes ineffective, it's time to change its tune--and that's precisely what Jody Bleyle and her friends have gone ahead and done, inventing a new-sounding voice for the disenchanted, a genre all their own. It's a stance that's somehow beyond queercore, or perhaps it's above it; soaring over the jokes and silliness that characterize it in San Francisco; soaring, also, over the murky world around it.

In Portland, after all, punk must exist side by side with the burgeoning redneck world that birthed Tonya Harding, and a conservative governmental streak that sheltered U.S. Senator Robert Packwood and doled out one of those all-purpose homophobic bills called Proposition 9.

Portland is also home to a group of people for whom the terms "gay" and "lesbian" seem totally outdated--like saying "colored person" or "Negro" rather than "black" or "African American." Dresch's Bleyle is a perfect example of this type of post-gay person. Charismatic, effervescent, humorous, smart, she is the embodiment of everything cool about queer.

From a distance, the trousered, bespectacled Bleyle conforms to the word "dyke," but up close and personal, she confounds it utterly. The first time I met her, she was lovingly toting a 3-month-old baby named Isabelle, the daughter of Brady Smith, bassist for the group Hazel. It turned out she is Isabelle's de facto nanny, taking care of her by day while she runs her record label out of her home, in exchange for free rent in Isabelle's parents' basement.

An unlikely maternal streak isn't the only way that Bleyle--who runs Candy-

ass Records and plays drums for Hazel and guitars in Team Dresch--confounds one's expectations. Her sport of choice is golf, and she doesn't call herself a punk.

In high school, Bleyle was into music--just not punk music. "Every single day after school, I recorded on a four-track with my friend John. I played music nonstop in high school. I was in every vocal group, every jazz band ... every stage band, every marching band, I played saxophone, and every day between all my periods I played the piano down in the practice room, and every day after school I went home and John and I recorded songs on our four-track. They just weren't punk. I thought punk was tuneless."

"I was a late bloomer," explains Bleyle. "I didn't come out in high school; it was totally under my radar. I didn't define myself as a punk or a queer; I was just a musician."

When Jody was 17, she moved from Connecticut to Portland to attend Reed College. "There was a great rock scene when I went to Reed. There were tons of bands and we'd have shows in the mailroom all the time, shows in people's dorm rooms and at houses, all the time. There were like 30 people there who were literally majoring in rock. There were people from Madison and Minneapolis, people from D.C. and from Boston ... all of whom would be like, 'Here, you have to listen to this Rites of Spring record. Here, you have to listen to Hüsker Dü.' And I was just like flooded within a couple of years.

And this was at the same time that SubPop was starting to happen and I would go down to Satyricon every night by myself and see Tad and Nirvana and the Fluid and I just loved all that shit. It was 1987."

Then one day at Reed, Jody continues, "I said to this boy, 'Is there any hard-core music that has melodies, that people really sing?' and he goes, 'Yeah, it's called melodic hardcore.' "

Pretty soon Jody was in Hazel, in which she played drums. But presently, she decided that Hazel wasn't fulfilling her emotional needs. "I just got sick of just being at a Hazel show and going, 'Oh by the way, I'm queer.' I was like, 'It has to be more than this. It has to.' I started to realize how [being punk and being queer] couldn't be separated, because unless I am vocal about this part of my life all the time, it doesn't exist."

For a while, Bleyle played in an all-woman band called Love Butt, which she liked because of its noncompetitive atmosphere. But none of the other members were gay. Then she met Donna Dresch at a Hazel gig in Olympia.

"After the show," Bleyle recalls, "I went off to her for about 20 minutes about how Tribe 8 was looking for a new drummer, and I was going to try out, and I couldn't take it anymore and I wanted to play with all dykes ... and blah blah blah, and I didn't even know Donna was a dyke!

"And then I met Kaia around the same time, and she was like, 'I'm playing with this girl Donna in Olympia, you wanna play with us? and I'm like, 'I know Donna, yes!' And ever since then it's been like ... that's the way it has to be."

Bleyle's casual acceptance of the difference between male and female social relations--particularly in a band context--is where Team Dresch shows such a huge leap forward in sociosexual politics. Remember the old joke "How many feminists does it take to change a light bulb?" and the answer is "That's not a funny subject"? What separates Team Dresch from previous angry women bands--the riot grrrls, from Hole, whoever--is its humor and courage.

But perhaps the most unique thing about the band is its nonjudgmental character. It is the first upfront gay band to successfully reduce queer issues to the dust they ought to be. In TD's hands, queer love--and hate, and lust, and betrayal--are merely love and hate and lust and betrayal: stuff that anybody can relate to.

Team Dresch doesn't shy away from gender specifics--"Growing Up in Springfield," "She's Crushing My Mind" and "Screwing Your Courage" are pretty damn frank--but their take on sexual orientation is all-inclusive. As Jody says, "You can't extrapolate from Pansy Division. You can't listen to their music and go, 'Well, I'm not a fag, but I understand wanting to be treated more fairly.' You listen to a Pansy Division song and you go, 'God--I didn't know you could use cock rings like that!' Whereas with our songs, the idea is just that, well, liberation is liberation."

From the straight point of view, this is crucial: it means that we--straight people--can join Team Dresch's noisome fray with the light of battle in our eyes as well.

That may sound specious--of course one could and should always support queer issues--but in fact so much of current queer culture is deliberately alienating to straight people. One can understand their impulse to shock the namby-pamby sensibilities of the despicable bourgeoisie, but there is something intrinsically defeatist about the alienating tactics of militant gay activists.

But Team Dresch is anything but defeatist. The minute you hear the band, you know what's been missing from the Superchunks and Sebadohs of the world. It might be going too far to say that Team Dresch put the venom back into punk, but its goals have a lot in common with the furious passion of English punk, circa 1977.

Like the British underclasses, Team Dresch's members feel oppressed and persecuted, even in danger, just for being who they are. So before most Team Dresch shows, the band holds a self-

defense workshop onstage to teach women and queers how to defend themselves against attack.

Men at Work: The cover of Pansy Division's 'Pile Up' album is not afraid to speak its name.

Hitting the Comfort Zone

TEAM DRESCH also makes a point of setting up shows that are friendly to queers. "Especially if it's a bar," says Jody, "we try to make sure it's advertised as a queer show, so that queers don't feel like they're going to a straight bar. Not that anyone's disinvited, but just as a step forward toward making it a safer space for everyone."

As Jody says, it's all about liberation--about building a community of like-minded people who you can feel comfortable with, about forging new values and reassuring yourself that others like you exist in this, the most sterile time in our history.

"People sometimes ask me, Does it feel bad or are you insecure to know that people just like you because you're in a band?" comments Bleyle.

"And I say no, because if someone likes me because I'm in Team Dresch, I believe that they do know me, and that they like me, and I like them and respect them too--and that is a really great feeling," Bleyle continues.

"The word 'punk,' " Bleyle adds, "to everyone it means a bunch of different things. The kids who see me out walking around Portland who have mohawks think that I'm a big poser, alternative-rock sellout or whatever. But I know--it's in the lyrics of our songs--that I would probably have committed suicide if Team Dresch hadn't formed.

"Because people, kids, who write me letters that say they need to meet me and that they needed to hear my music and that it's helping them get through a really hard time and they gave it to their friend who's having a really hard time ... those things literally take my day from what's my point of being alive today, to going, 'OK, there is a point.' "

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)