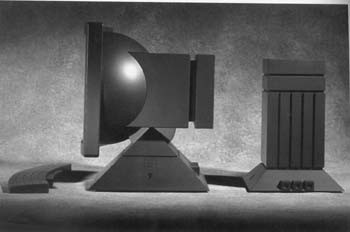

Digital Dreams: Apple's futuristic hardware designs are lovingly displayed in 'AppleDesign.'

Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders

By Jim Carlton

Times Books, $27.50 cloth

AppleDesign: The Work of the Apple Industrial Design Group

By Paul Kunkel and Rick English

Watson-Guptill Publications, $44.95 cloth

Apple's problems are not new, but its best creations are still beautiful to behold

By Tom Geller

IN MARCH, shortly after Apple laid off 30 percent of its workforce, I went to a party at the home of one of the company's recently canned employees. But instead of the funereal atmosphere I'd expected, these unemployed folks were thrilled to be free of the beast. No more idiotic Apple politics, they sighed, telling stories of management working at odds with engineering.

They were happy to have their severance packages and were looking forward to their next jobs. And they probably wouldn't have to wait long. As venture capitalist Ann Winblad likes to say of computer professionals, "There's zero unemployment in the Valley."

I'd grown up believing the Apple mystique, so their elation at being fired was a shock. What had happened to the company where, 15 years earlier, applicants camped out in Human Resources for days in hopes of landing a job? What happened to the belief that Apple would, as co-founder Steve Jobs exhorted early employees, change the world?

The answers are spelled out in painful detail in Jim Carlton's Apple: The Inside Story of Intrigue, Egomania, and Business Blunders. Carlton draws from more than 150 interviews and several years as a technology reporter for the Wall Street Journal to make his point that Apple's current problems are firmly rooted in a history of arrogance, shortsightedness and greed dating back to the company's founding 20 years ago.

If you're a recent follower of Apple's fortunes, you've seen a string of questionable actions leading to the loss of more than a billion dollars in the past year. Carlton's book shows that ineptitude is nothing new, describing dozens of missed opportunities.

For example: The company nearly killed the underpowered and overpriced Macintosh 128K with unreasonable market expectations; it insisted on high profit margins at the expense of market share; declined to license the Macintosh operating system for 10 years; and has failed to modernize its crown jewel, the Mac OS, despite years of pie-in-the-sky promises and hundreds of millions of R&D dollars. (The industry watches Apple's current effort, code-named Rhapsody, with an extremely jaded eye.)

Along with a recitation of dates and events in the corporate saga, Carlton tries to dig into the participants' psychologies. He describes Jobs' magnetic effect on an audience, as well as the bullying tactics he used on employees. He shows how a string of presidents and CEOs failed to provide Bill Gates-like effective leadership--from the abrasive Mike Scott through the deferential John Sculley to the peculiar Michael Spindler and the ill-fit Gilbert Amelio.

In these matters, Carlton generally does a good job capturing the chaos that is Apple. He follows along as the company careens from unlikely success to unexpected failure, mostly tying events together by following their players. As a result, we see individuals' quirks and flaws repeated in numerous circumstances, and the book takes on the feeling of Greek tragedy.

Dry, With a Twist

UNFORTUNATELY, Carlton's dry writing style doesn't match the story's drama. The author suffers from an ailment common in the daily newspaper genre: in order to maintain a pretense of objectivity, he avoids signs of personal involvement.

He'd have done well to show his hand more often. One of the book's most entertaining moments occurs when Carlton describes chasing then-CEO Spindler around a trade-show floor while the elusive neurotic flees the building through a side door. A better example of a personal business history is found in Jerry Kaplan's Startup; there, the author lets his emotions show, but doesn't let them get in the tale's way.

On top of that, the book desperately needs to rid itself of redundant descriptions and paragraphs. How many times do we have to hear that Satjiv Chahil is "beturbaned," that Debi Coleman left Apple to "battle a weight problem" or how Michael Spindler got the nickname "The Diesel"? This repetition reminds us who the players are, but it's not nearly as useful as a chronology, glossary, dramatis personae or photo section would be--all of which the book lacks.

In essence, Apple: The Inside Story serves well as a reference book, a starting point for future discussion. Carlton himself avoids deep analysis until the last two chapters--and more's the pity. But his final thesis there may be right on: that nothing short of a buyout or a miracle can save Apple from its legacy of squandered opportunities.

Polished Pictures

LEST WE FORGET, Apple has also left another legacy: beautiful, groundbreaking hardware design. It's this legacy that Paul Kunkel and photographer Rick English report in AppleDesign: The Work of the Apple Industrial Design Group, a gorgeous coffee-table book. In form and function, it's similar to a 1987 Apple-produced retrospective called So Far--that is, it blows the company's horn with beautiful pictures and soft, laudatory words.

While the earlier work was Apple's own paid advertisement, AppleDesign is a sincere and credible look (despite numerous irritating typos) at one of the company's greatest strengths. It charts designs from their earliest stages, some of them so vague and fantastic as to give the book a dreamy quality.

Perhaps that's appropriate for Apple, a company where dreams have often taken precedence over reality. When Apple launched the Macintosh with the now-famous "1984" commercial, it also instituted another campaign: "Apple II Forever." Then, as now, it asked us to look toward its version of the future. But in a company as chaotic, disarrayed--and vision-centered--as Apple, the future exists only in soft-edged, rounded-corner dreams.

Tom Geller is an independent computer-industry analyst and consultant.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)