![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

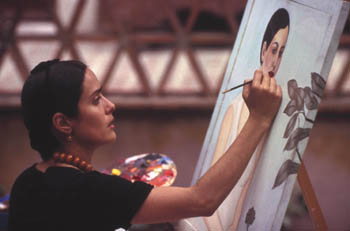

Frida's Touch: Salma Hayek applies the finishing touches to her portrait of the artist as a young woman. Kahlo Waiting 'Frida' pays homage to the Mexican artists sensuality and creativity--but not her politics THE DELAYED biopic of Frida Kahlo, Frida, is finally here. The personal and romantic agony of this artist has been shaped into the form of a basically mainstream film. It's sumptuous, with the year's best use of color by photographer Rodrigo Prieto, who shot Amores Perros. The production design and art direction are a tribute to Mexican decoration and crafts. Playing Frida is the film's co-producer, the most lush-lipped and voluptuous actress since Sophia Loren: Salma Hayek. Though it's a financial risk to make an R-rated movie in these cowardly days, director Julie Taymor hasn't scrubbed clean Frida's sexually ambidextrous love life. As famed photographer Tina Mondotti, Ashley Judd does a slow dance with Frida; Saffron Burrows turns up, stiff as a board in a New York fling. Taymor, whose Titus was an example of the Fellini-goes-to-Soho style, cools it here. The moments of surrealism are all inspired, including animations of spilled drops of Kahlo's blood forming into flowers or butterflies. The film aptly reflects the macabre art of a woman whose face was her subject--most of her 200 paintings are self-portraits. That the paintings sometimes come to life makes dramatic sense, even in the last shot, taken from a painting, The Dream, that Kahlo created years before her death. Taymor perfectly rhymes Mexican fatalism with the art and life of the nation's most popular artist. Kahlo is, as novelist Carlos Fuentes put it, "The Mexican St. Sebastian," as famous for her wounds as for her work. At 18, she was almost killed in a traffic accident. After countless operations, the artist was wedged into 28 different kinds of corsets in an attempt to give her relief from her chronic pain. With a superb effort of will, she focused on her art and squandered her energy on her turbulent marriages to Diego Rivera. For a biopic--especially for a biopic of a woman who spent years of her life on her back in bed--Taymor's film flows smoothly and quickly. After recovering from her accident, the young Kahlo befriends Diego Rivera (played by Alfred Molina), who champions her work. Diego never had trouble finding lovers, and his refusal to stay monogamous had factored in ending his two previous marriages. Though Frida agreed to an open marriage, this vow was tested with her brief affair with the exiled Leon Trotsky (played warmly by Geoffrey Rush). That Frida's tale is told as a love story helps the commercial chances of a film shaped in the MGM style. Four screenwriters--including Gregory Nava--have worked to make sure there's never a scene in which there are two possible meanings of what's going on. Which of the four writers gets credit for Rivera's line to Frida, "Thank you for making a fat, old, crazy Communist a happy man"? Taymor's visual ideas are often deft. Frida's love scene with Trotsky is shot in soft focus as the camera sweeps by their bed, the scene coming into sharp focus for an instant as we pass by the lenses of Trotsky's eyeglasses on a bedside table. Frida and Diego's first trip to New York finds them wandering through a collage of the city. The finale presents Frida's first solo show at the Lola Alvarez Bravo gallery; her arrival is a surprise appearance because she is too sick to rise and must be transported in her bed. This was no surprise in real life. It's staged for the same reason that the Nobel speech was made up in A Beautiful Mind: to hit the audience hard. Another choice for Taymor and company would have been to show Kahlo not at the art opening but at her actual last public appearance, in a wheelchair at a march protesting the CIA-sponsored overthrow of the left-wing president of Guatemala, Jacobo Arbenz. Kahlo, who said her three aims in life were to be a Communist, an artist and Diego Rivera's lover, has gotten two out of three in Frida: her deep and never-renounced politics are treated like a silly affectation, like her habit of carrying monkeys on her shoulder. While Frida celebrates the passion of an artist who ended up blue-chip (one of her paintings recently sold for $2.3 million), and is at least as honorable as Lust for Life, the film is a throwback to the noble old popcorn tradition of a girl acting bad because a man drove her to it.

Frida (R; 118 min.), directed by Julie Taymor, written by Clancy Sigal, Diane Lake, Gregory Nava and Anna Thomas, based on the biography by Hayden Herrera, photographed by Rodrigo Prieto and starring Salma Hayek and Alfred Molina, opens Friday at selected theaters valleywide.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the November 7-13, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.