![[Metroactive Movies]](/movies/gifs/movies468.gif)

[ Movies Index | Show Times | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

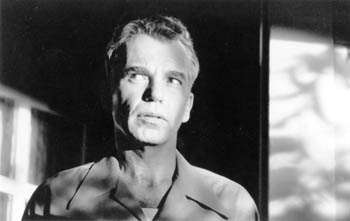

Close Shaver: Barber Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton) is tired of barely scraping by.

Barbered Wire

The Coen Brothers' 'The Man Who Wasn't There' is crypto James M. Cain

By Richard von Busack

WHY IS IT that The Man Who Wasn't There lacks the kind of advance buzz you'd expect from a movie that follows O Brother, Where Art Thou? It's because the Coen Brothers--Joel, directing and co-writing; Ethan, producing and co-writing--have failed to get a handle on the themes in writer James M. Cain, in contrast to their lovable Raymond Chandler parody The Big Lebowski.

The mostly humorless The Man Who Wasn't There represents the Coen Brothers' salute to Cain's fatalistic novels, especially The Postman Always Rings Twice. Here, as in many other of today's neonoirs, we see the stately moviemaking style usually inflicted on grand literature. That's what happened when Cain's vivid, greasy pulps became regarded as classics.

The film is set in Santa Rosa in 1949. Ed Crane (Billy Bob Thornton), a morose barber, is looking for a way out of his job. A slick out-of-towner named Creighton (Jon Polito) entices him with a business plan. Ed needs several thousand dollars to buy in as a silent partner.

Meanwhile, the barber starts to suspect that his wife, Doris (Frances McDormand), is sleeping with her boss, Big Dave (James Gandolfini), owner of the local department store. Crane decides to blackmail Big Dave for the money to pay Creighton. The plan goes wrong, and Big Dave ends up dead.

The first half hour is slick, economical storytelling. Thornton is, at first, amusingly unrecognizable. He seems to have been starched. His mouth is collapsed in disapproval, his hair slicked back into a stiffly clenched pompadour, a la Hugh "Ward Cleaver" Beaumont.

Thornton cuts back his dialogue to a bare flickering response, and only his deep grumbling voice hints at the inner anger beneath the unemotional talk. The typical Cain character had big, splashy appetites.

For some reason, the Coens put a bottled-up Jim Thompson nut case in a Cain plot.

The Coens follow the Cain scheme so much that they even load in a lumpy third-act subplot about a local girl named Birdy (Scarlett Johansson), whose classical piano playing touches something in Crane's heart. This discursion sticks out as badly as the passage about the lady lion tamer in The Postman Always Rings Twice.

Apparently, for Cain, sections like this were meant as new avenues of hope for our rat to run down before he ended up in the trap. If a Cain character avoided falling into a pit, the author grabbed the hole and moved it--as Bugs Bunny always did--so we could see the plummet we were waiting for.

The Coens' film looks avant-garde, but it evinces the wooden conventions of Hollywood past: overproduction and acting with quotation marks around it. Photographer Roger Deakins' black-and-white images are as pristine and spotless as Crane's barber's tunic. Deakins, the Coens' regular cinematographer, is an expert at nostalgia, but nostalgia is probably the last quality a Cain-oid film needs.

Our moneyless barber lives in a showpiece house and works in a barber shop as big and clean as an operating room. Similarly, the acting is showy. There's never any doubt in our minds who everyone is--and doubt should be part of a mystery.

Except for Gandolfini's Big Dave, the supporting acting seems too broad for suspense. Michael Badalucco, who played Baby Face Nelson in O Brother, Where Art Thou?, shows up as Ed's racketing, pestering brother-in-law who owns the barbershop.

Polito looks like Akim Tamiroff. He wears a toupee that, like Tamiroff's rug in Touch of Evil, seems to have a life of its own--but when an actor reminds you of how relatively restrained Akim Tamiroff was, he's overdoing it.

It's also kind of Bizarro-world film when McDormand, an actress who radiates modesty and decency, plays the bad girl, and Johansson, a humid Lolita, plays the good girl. Throughout, the acting displays the usual problem with the Coens' primarily serious work. Here's cartoonish evil without cartoonish wit or energy; here's dialogue that's flamboyant and yet self-conscious.

The Coens' most serious work is usually inferior to their comedies. Barton Fink and Miller's Crossing are tragedies punctured by gross caricature. Despite strange and exciting passages, they're mostly unwatchable. In the much better Fargo and Raising Arizona, the comedy is ascendant. And The Man Who Wasn't There, a tragedy, isn't just gross but frigid.

The Man Who Wasn't There recalls film critic Manny Farber's famous dialectic: white elephant vs. termite art. By "white elephants," he meant cluttered big-budget films that aged badly into the kind of relic you find in a thrift store. These films decayed compared to the work of slapstick comedians and film noir directors, low-budget talents who nibbled around the edges of Hollywood, working under the wire and under the radar.

The Man Who Wasn't There is meant as termitey film noir, but it has a terminal case of white elephantiasis.

[ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

![]()

Photograph by Melinda Sue Gordon

THE MAN WHO WASN'T THERE (R; 116 min.), directed by Joel Coen, written by Joel and Ethan Coen, photographed by Roger Deakins and starring Billy Bob Thornton, Frances McDormand and James Gandolfini, opens Friday at the Camera One and Century 25 in San Jose and Century 16 in Mountain View.

From the November 8-14, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.