![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

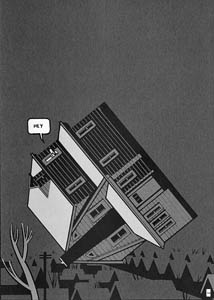

F.C. Ware; Pantheon Books 100 Years Of Solitude With 'Jimmy Corrigan,' Chris Ware brings the art of the comic book into the new century

Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth By Chris Ware Pantheon; 380 pages; $27 cloth COMIC BOOKS have always been the solace of the powerless. Writing and publishing comics was an industry created by urban Jewish immigrant kids in the 1930s. When tracing the history of comics, few observers fail to mention the Golem, the Jewish legend of the superheroic living statue that protected the persecuted Jews in the ghetto at Lodz. The Golem spawned Superman and Frankenstein alike. The comic-book hero, son of the Golem, is a shrimp with secret powers, like Captain Marvel. He is an orphan who has turned his solitude into a weapon, like Batman. He is a meek square, eager to please, like Clark Kent. The best horror comics were published by William Gaines, son of Max Gaines, the man who helped create the comic book as we know it. Tales From the Crypt and William Gaines' other titles were elaborate revenge fantasies in which the unjust of the world faced poetically apt punishment. Despite the violence in comic books, the creators of comics are usually just like their readers: reticent and shy. Yes, they're boastful, overcompensating oafs, sometimes. Types like the "Comic Book Guy," the obese, pontificating fan on The Simpsons, can be easily found at any comics convention. But whether brash or nervous, all comics fans look back to a time when comic books were printed by the millions. The fans are members of a diaspora culture. They are slaves of a medium whose best days, all agree, are over. If any one writer can turn around the declining course of the medium, it's Chris Ware, who has gone further in creating a beautiful comic book than any other artist. Ware has also journeyed inward, going further than any other comic-book artist in unveiling the meekness of the comic-book fan. Puzzle of Survival WARE'S NEW COLLECTION, Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, sums up a century's worth of comics. His images, lettering and language remind us of the long-dead craftsmen who first developed comic art, and Ware brings that art to the present by using comics as a tool for confession and self-expression. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth is part of what Ware calls "the universally unfashionable world of the comic strip." Movies, television and video games should have made the comic book extinct; thus the survival of comics is a puzzle even to the artists like Ware who toil so hard at the art. He works in a medium with a forgotten past and an uncertain future, and thus his twin themes are lost history and abandoned children. Fantagraphics originally printed the Jimmy Corrigan saga in a series of comic books titled Acme Novelty Library. Ware describes his comics as "a bold experiment in reader tolerance." Ware's story danced around in time and space from issue to issue of Acme Novelty Library. His books were printed in various shapes and sizes, making it hard to tell where, exactly, one could pick up the thread of his tale. Vital information was concealed in panels the size of a thumbnail; clues were hidden in dream sequences. Now assembled in one volume, Ware's work is revealed as coherent. Jimmy Corrigan: The Smartest Kid on Earth, has, in Nabokov's phrase, the wings and claws of a novel. The ordinary comic book seeks to be dynamic. Splash-page pinups of heroes leap at the reader, fists forward, trying to burst into three dimensions. Ware's contemplative work, on the other hand, is always flat and usually small, with sequences of panels not much bigger than postage stamps. With these little rows of squares, as alike as ellipsis dots, Ware cuts time into fractions, preserving small moments of burning shyness. The book follows three generations of Midwestern men all named Jimmy Corrigan. The dates here may not be accurate; I had to estimate them. The closer Ware's timeline approaches the present, the looser it gets. "Jimmy I" is Jimmy Reed Corrigan (b. 1883), who is beaten and neglected by his father, William Corrigan, a brutal, unsuccessful Chicago glazier and maimed Civil War veteran. Jimmy Reed's son, James William Corrigan (1921-1987), or Jimmy II, is a Marine vet and bartender in the fictional town of Waukosha, Mich. In turn, his son, whom he hasn't seen since the boy was 6, is the virginal, mother-dominated Jimmy III (1941-present), a slouching Chicago office worker with a drooping, potato-shaped face. One typically uneventful day in the 1980s, Jimmy III receives a letter, from the father he never really knew, enclosing an air ticket to come and visit him in Michigan. This first meeting since Jimmy III's childhood is a thorough disaster. Jimmy II, now an old man, tries to reach out to his bitterly shy son through man-to-man kidding around. He is defensive about abandoning his son since early childhood. ("You'd think this whole country was a bunch of child-abused mental patients," Jimmy II grouses while they watch some casualties of life on the Oprah/Sally/Rikki shows together.) Jimmy III, unused to the company of men, has fantasies of murdering this strange father, or being murdered himself. Ware knows how to make silence deafening by spreading out an uncomfortable moment into a dozen minute panels. "The popular late-20th-century social process fondly known as 'bonding' has yet to adhere our two decidedly un-magnetic protagonists," Ware notes. Jimmy III's troubled relationship to his father cuts a deep current through the book. Superman himself (1931-forever) turns up as both an ideal of manhood and also as a swag-bellied bully. In the book's preamble, Jimmy III catches glimpses of a primal scene between his mom and a cheap actor who plays Superman at a hot-rod show. ("Tell your mom I had a real good time," the man says as he sneaks out in the morning.) Superman, the archetypal comic-book figure, isn't just the father Jimmy III never had--he's the bluff, hearty man he'll never be. (As an adult, Jimmy Corrigan III still reads Superman comics, still eats cold cereal as he reads.) Things to Come A STOLEN CAR, a minor injury and a severe accident deepen the scenes of Jimmy III's exquisite discomfort. As a relief from the two men's stalemate, Ware takes us back to the childhood of Jimmy I, whose lonely, painful life is contrasted with the construction and opening of the nonesuch of the times, the great Chicago Columbian Exposition of 1893. In his pastel-colored panels, as pretty as the fairy palaces the pioneer cartoonist Winsor McKay drew in the 1890s, Ware shows us the wonders of the future as predicted by the fair. It was a water park with allegorical statues built on the shore of Lake Michigan. The Exposition both celebrated the 400th anniversary of the landing of Columbus and lauded the century to come. Then we see that future realized, in the highly ordinary town of Waukosha. It's there that all three Jimmy Corrigans--grandfather, father, son--encounter each other one last time. Ware's drawings of Waukosha are as perfectly satirical as they are perfectly accurate. (Ware includes a set of imaginary trading cards highlighting the town's wonders, describing them in high-flown language: a water tower, a Stop 'n' Spend, a Dairy Queen, a Greyhound station.) Ware leaves behind the simple, solid comic-book spectrum: the red, yellow and blue Superman, and the black and blue Batman. His Waukosha illustrations are as softly colored as a Japanese woodblock print. Spare and yet detailed, each little drawing opposes the visions of the last really influential avant-garde cartoonist, Robert Crumb. In Crumb's Midwestern cityscapes, the skies are lowering, polluted, bound up with ugly power lines, perforated with trash-can-sized transformers and telephone poles. His drawings are the artistic revenge of a genuine Luddite. Crumb once did a poster titled "A Short History of America" that showed the transformation of a virgin meadow into a besmirched, traffic-laden intersection, with the words "What next?" Crumb sees American history as a downward spiral. Ware, a less furious artist, sees transience in these images of malls and fast-food joints. Ware knows that Waukosha's cinder-block businesses--stark and square against rose or aqua horizons--are all temporary things, transparent, as insubstantial as the buildings of the Columbian Exposition. Waukosha is a remarkably boring town, but it's also the site of the most ravishing moment in the book. Jimmy III, stunned by a rare instance of praise, steps outside his grandfather's apartment to clear his head. He stands in the freezing dawn in an empty parking lot. There are patches of snow on the ground. On a street lamp, a dimly seen cardinal is perched, singing a one-note song. For a moment, it seems that Jimmy III has the capability to make sense of the sad 100-year history of his family. The Anti-Superman WHEN AN ARTIST describes what seems like flawless work as "flawed"--as Ware does in his afterward--you do want to go over it again ... not to nitpick, but to see what he meant, to get a deeper understanding of the work. What might the flaws be? Maybe it's a cliché that Jimmy III's adopted stepsister Amy, is, as an African American, the only character emotional enough to be outside the loop of repression and loneliness that could be called Corriganism. Amy is the only one to react to the amazing banality of Waukosha ("God, I hate this town"), and Ware also uses her to burst the standard cliché that all African Americans have good taste in music--she's a Barry Manilow fan. Amy also says she's not a "comedienne"--Ware puts the word comedienne in quotes, underscoring that Amy isn't going to be part of the persistent racist symbols (like a Jim Crow magic-lantern slide) he's been using to counterpoint the supposed majesty of the American century. Maybe it's a weakness for this book to end on an optimistic note. Ware offers a possible reprieve for Jimmy III, introducing a girl into his office who is as socially awkward as he is. The possibility of romance goes against the unpitying way Ware has treated his hero, this sad heir to the ages, the anti-Superman. Jimmy Corrigan III is at once the most boring man on the planet and a surrogate for the reader who can never get over childhood, get over shyness, get over fatherlessness--those who sometimes seek refuge in comic books. Tolstoy wrote, "Consciousness is immovable. Due to this alone there is the movement which we call 'time.' If time moves on, then there must be something that stands still." Ware's comic art--as delicately colored as Japanese woodblock prints, fresh, incisive and satirical--has above all captured this idea of immovable consciousness during the course of decades. With this story of 100 years of solitude, Ware has taken the art of comics into the new century. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 9-15, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.