Musical Magritte

Robyn Hitchcock's music is more beautiful than ever on new 'Storefront' album

By Gina Arnold

'BEAUTIFUL." That's the first word that would come to my mind if a psychiatrist played that word-association game with me and said, "Robyn Hitchcock." Sure, beauty is in the eye of the beholder. But whenever I behold Hitchcock, I'm struck by the beauty not just of his music but of his spirit.

Alas, a beautiful spirit is not something one meets very often in the field of rock music, a sad fact that may explain why Hitchcock has fallen short of megasuccess in the industry, despite having gathered the highest possible accolades for his 19-odd (and 19 odd) records.

Hitchcock is beloved by critics and has a cult following, but he's never quite made it into the mainstream. This is not surprising, since his lovely melodic songs, which draw their musical inspiration from the Byrds, Syd Barrett and John Lennon, are far too lyrically strange to charm the masses.

Hitchock is the Rene Magritte of rock & roll, bursting with surreal ideas that make deep psychic sense. In his world, it rains prawns and frogs, and the past and the future coexist in the present. It is not a world that appeals to everyone, but those who get it, get it good.

His newest album, Storefront Hitchcock, is the soundtrack to a film made by one of his fans: Jonathan Demme, Oscar-winning director of movies like Melvin and Howard and The Silence of the Lambs. Demme is a longtime music fan (he made the Talking Heads' in- concert movie, Stop Making Sense) and has had the innate sensitivity to capture Hitchcock at his most intimate and communal.

Live, Hitchcock--playing solo acoustic with only the occasional violin and one or two extra guitar parts--is known as much for his monologues as for his songs. Lyrically, he often dips into the surreal, and the same goes for his stage patter. But nothing he says is entirely crazy.

"I don't know what kind of church you like to imagine, but I like to imagine one with carcasses," he begins one such monologue. On another, he posits a hellish journey in which bodies are swaddled in duct tape and conducted about by two Minotaurs, a strange circumstance that somehow causes a total panic in greater London.

Conveniently, these absurd monologues have been set apart on separate CD tracks, so they can be programmed in or out for your listening pleasure. They're certainly worth listening to once, but perhaps not if, say, you're listening to the CD in your car.

Storefront Hitchcock draws its material from more recent records, namely 1993's Respect, 1995's Eye and 1996's Moss Elixir, and inevitably its excellence depends on the choice of material. There are those in this world who might prefer Hitchcock's last live LP, 1985's Gotta Let This Hen Out, which showcases earlier material but which does not include any spoken-word selections. Storefront Hitchcock also contains a fabulously subdued cover of the Jimi Hendrix song "The Wind Cries Mary" and four new songs, which are among the album's best material.

Hitchcock is always at his very best when he writes nostalgically--who can forget the poignancy of the songs "Winchester," "A Raymond Chandler Evening," "I Often Dream of Trains" and "Trams of Old London"? The opening track here, "1974," is one of the best of that breed. "It feels like 1974," Hitchcock sings, "ghastly mellow saxophones all over the floor. ... It feels like 1974/you could vote for Labour, but you can't anymore."

"No, I Don't Remember Guildford" is another such paean to the past. "What was the something that jogged my memory? Not the cathedral or the pool/But I'm a little past it, near enough to be scorched, not blasted." Those two songs and "Beautiful Queen" are the album's highlights.

If all this sounds somewhat abstruse and arty, please remember that it is mitigated by the touch of Hitchcock's fingers on the strings of his acoustic guitar. He is one of the people who helped to perfect the bell-like chime of the 12-string Rickenbacker that is the basis of music by R.E.M., the Byrds and Tom Petty. This is jangle pop, at its most simplistic.

In some ways, Hitchcock never gets too close to real emotions. "Where do you go when you die?" is as close as it gets for him--and indeed, imminent death and our possible resurrection seem to be the underlying themes of the record, which essentially ends with the gentle, if slightly apocalyptic, pronouncement "I'm not afraid to be the only person on the planet/I'm not afraid to be the only person in the world with you."

In fact, love is not a subject that Hitchcock approaches very often, but given the wealth of material on that subject, that's kind of a relief. Indeed, in this overwrought and angst-ridden world, there is something peaceful about listening to music that detaches itself from the tiny personal issues of life and merely grapples with the big ones.

[ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Maintained by Boulevards New Media.

![]()

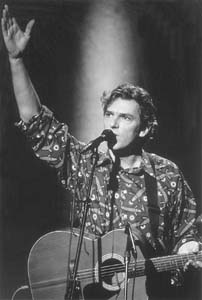

Start Making Sense: Even his most surrealistic lyrics seem to add up in Robyn Hitchcock's oddly compelling new realease, 'Storefront Hitchcock.'

Start Making Sense: Even his most surrealistic lyrics seem to add up in Robyn Hitchcock's oddly compelling new realease, 'Storefront Hitchcock.'

From the November 12-18, 1998 issue of Metro.

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)