Robert Scheer

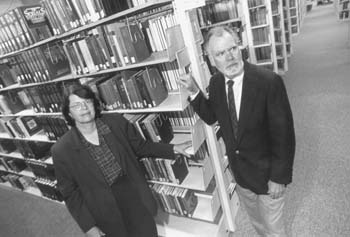

Booked Up: Jane Light, San Jose city librarian, and James Schmidt, SJSU librarian, believe the joint plan will meet two sets of pressing needs.

An ambitious plan to bridge the town-gown gap with a huge joint-venture library may mean less of everything for everybody.

By Michael Learmonth

WHEN JAMES SCHMIDT came to Silicon Valley to take a job as San Jose State's head librarian, he and the university clearly had big plans. Schmidt's résumé already boasted several significant construction projects, including the Lyndon Baines Johnson Library on the campus of Southwest Texas State University, five library projects on the Ohio State campus, and two new libraries in the Mississippi State University system.

"I'm assuming a body of experience in planning library buildings was one of the things the university found attractive when I joined the team in 1992," Schmidt says modestly, during an interview in his office on the top floor of SJSU's Clark Library.

The university wanted to consolidate library holdings that currently occupy two campus buildings, Clark and Wahlquist, and Schmidt worked to further that rather pricey plan. But in 1994, voters rejected a bond issue, indefinitely postponing all new construction in the 22-campus California State University system.

Soon after the bond failed, and with State's library buildings running out of shelf space, Schmidt says, interim university president Handel Evans bounced a dramatic idea off San Jose Mayor Susan Hammer.

Less than two years later, this past February, the plan became public. The economy was up, crime was down and the city budget had just sailed through with nary a fuss when Mayor Hammer stood in front of a bank of video monitors to give her State of the City address. But rather than reel out a list of past accomplishments, the mayor took the occasion to unveil a vision for the future: a proposal to build a new San Jose library.

Hammer described a joint venture, built, paid for and shared by the city of San Jose and San Jose State University. Students and citizens would enjoy a state-of-the-art facility, located on the edge of campus, replete with workstations and hard-wired with the trappings of the Information Age. It would represent the kind of creativity and innovation that one would expect from a big time city and a university in the middle of Silicon Valley.

Back then, the mayor was long on vision, short on details. Ten months later, three committees have been formed, several focus groups have been consulted and a plan is taking shape.

The committees are looking at the corner of N. Fourth Street and E. San Fernando Avenue--the current site of the Wahlquist Library. When (and if) it's completed, the library will be huge--almost twice the size of the new San Francisco main library--making it one of the nation's biggest libraries.

The response from the campus community, however, was not what Hammer expected.

Almost 300 faculty members have since signed a petition against the proposal, and an increasingly vocal cadre of students and faculty question whether the merger is a good idea at all.

Double Issue

FOR THE CITY, the timing of the proposal couldn't have been better. City officials had long lamented that the McEnery Convention Center, built in 1989, wasn't large enough to compete for conventions with other cities. The Redevelopment Agency wanted to knock down the 27-year-old Martin Luther King Library and expand the convention center onto that site.

By collaborating with the university, the city could avoid the headache of searching for a new site for the library and could link the project to the proposed Civic Center complex the city hopes to build across East San Fernando from the university.

While the idea may have been born from fiscal necessity, its novelty has many officials intrigued. City librarian Jane Light is excited about opportunities to collaborate with the university. She's bubbling over with ideas on how both libraries could benefit from the merger.

Over the past five years, library funding at SJSU has slipped 25 percent, and new book acquisitions have fallen 50 percent. San Jose spends a mere $22 per citizen on its library system, half what Light's former employer, Redwood City, spends per capita.

Light came to the city of San Jose six months ago from Redwood City, where she was city librarian and, for a time, deputy city manager. She knew when she took the job in San Jose that the main library was too small (115,000 square feet) for a city of almost a million.

Schmidt believes the joint library would have to be at least 525,000 square feet. He says that will cost in the neighborhood of $100 million--a lot less than two new facilities. The two libraries could also combine staffs and save money by eliminating duplicate volumes and services, he says. He held up the reference section as an example of another place where money could be saved.

While the joint venture would stretch resources, it is uncertain whether the needed funds are available at all. The California State University system has about $150 million to spend on capital projects throughout the 22-campus system each year, and the competition is fierce. There is evidence that campuses willing to go outside the university for some funding are more likely to get some of that money.

In 1994, Cal State Los Angeles collaborated with Metrolink, Southern California's regional commuter train, to build a station on campus. Cal-Poly built a performing arts center in 1996, with around 15 percent of its funding coming from the city of San Luis Obispo. And Sonoma State will break ground this spring on a joint library and tech school with the Rohnert Park-Cotati Unified School District.

Off the Shelves

BRUCE REYNOLDS is chair of the history department at SJSU, a member of the Academic Senate Library Committee and a strong opponent of the joint library. He concedes that there are a lot of reasons for the city and the university to collaborate, but worries that few of them have to do with students.

"My view is that this thing is being pushed for all kinds of reasons other than for how well it would serve the university or the city," Reynolds says. "I'm afraid the functionality of the library for the public and the students will be lost in the shuffle."

English professor Scott Rice (famed on campus for launching the annual Bulwer-Lytton bad-writing contest) agrees with Reynolds and thinks that city and SJSU officials are playing fast and loose by attempting a merger that has never been conducted on this scale.

"English teachers have a way of getting hysterical when something like their library is being treated cavalierly," Rice admits. But he points to declining acquisitions as evidence of a prevailing attitude among the university trustees which he finds disturbing, one which holds that the classics are great for schools like Stanford, but commuter-university students benefit more from access to the latest technological gimmicks.

"This is the mentality we are dealing with, and I can't separate it from the library issue," Rice says. "A proposal like the merger can only be taken seriously in a certain intellectual climate, and it is one that devalues the importance of higher education in the lives of middle-class and lower-middle-class students."

Jo Whitlatch, a tenured SJSU librarian, agrees that the two libraries' clients are just too different for the merger to work.

"Saying one building will solve both functions is a questionable proposition," she argues. "The reference questions you get in the public library system are very different. Public libraries get questions like What is a good current novel? or price quotes for used cars over the phone."

To assuage the skeptics, Schmidt insists that what is being considered is not a "merger," but a "shared-use facility."

The distinction is important for the constituency on campus that opposes a library "merger" but could live with an arrangement in which the libraries remain separate but share a building.

"I'm not opposed to a building with two libraries in it, but I'm very much opposed to a merged library," Reynolds explains. Reynolds' position has become known among the various committees as the "duplex model." This would allow for a joint facility--basically a huge building with a wall separating the two collections, both literally and bureaucratically. The collections would not intermingle, and SJSU presumably would have greater control over who gets access to the university collection.

Schmidt, however, wants to see the two libraries become one. He argues that the duplex model would require a larger building and rule out some of the efficiencies a joint library would enjoy.

"I think that the duplex model misses most of the collaborative opportunities that the joint facility offers," Schmidt says. "It misses so many that I have to ask, Why do it? Why not go it alone?"

Schmidt chides joint-library critics for their fear of innovation.

"I think the joint library is frightening largely because of its uniqueness," Schmidt says. "A change in the status quo engenders resistance."

On this, Rice would probably agree. But he believes that in the sanctified halls of academia, and especially between the dusty stacks, resistance to the whims of expediency and economics is a virtue.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

![[Metroactive News&Issues]](/gifs/news468.gif)