![[Metroactive Arts]](/arts/gifs/art468.gif)

[ Arts Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

Click here to buy 'Frida Kahlo: The Paintings' at Amazon.com |

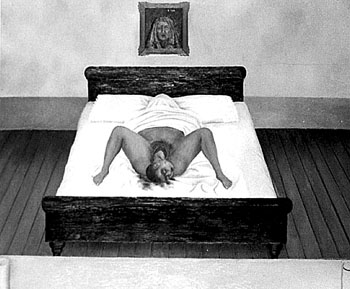

Frida Inc. Searching out the truth in the raucous rebirth of the original bohemian Latina--Frida Kahlo By Gretchen Giles SHE WAS furry-mouthed and hugely browed, contracted leg-withering polio as a child, was impaled by a streetcar's hand-rest as a young woman, endured more than 30 surgeries, matured into a crippled, bisexual Communist who twice married a man said to consider extramarital sex tantamount to a "handshake," and has even been dead for some 48 years. And yet none of this has dulled Frida Kahlo's cool quotient in the slightest. Most recently, she has been laboriously exhumed to habitation within the lithe, pampered, busty form of Salma Hayek for her eponymous biopic. Right this minute, Frida Kahlo's image can be found somewhere on the planet: dangling as earrings, sported on T-shirts, pasted to walls, flipped past in books, magnetically adhered to refrigerator doors or toted around on bags. A nice hot pot of soup somewhere is resting upon a Frida-adorned trivet, and endless coffee mugs are, in a subtle manner known only to the mass-market intelligentsia, expressing an affectionate affiliation with the longest-suffering minor painter of the 20th century. While 65,000 websites tout her or sell her, Kahlo (1907-54) only produced 200 paintings in her brief lifetime, most of them quite small, most of them self-portraits. Indeed, in the view of her biographer Hayden Herrera, all of Kahlo's works were self-portraits--be they of fruit or flowers or her own distinctive visage. Madonna jealously hoards Frida's paintings, recently retorting in the press that she "would not be friends with" anyone who didn't like her Kahlo piece titled My Birth. Madonna mister, Guy Ritchie, is reportedly "creeped out" by the work, which depicts a shrouded woman engaged in normal obstetrics upon a bed. The media hotly questions whether Madonna's children should be allowed to view it. And the nonsense continues. Jennifer Lopez engaged in a unladylike public catfight with Hayek for the film role, and just a few years ago designer Jean-Paul Gaultier sent a faction of shivering skinnies down the catwalk in Frida braids and transparent shirts boasting big bras, as though haute couture mistresses everywhere should stride Manhattan in perpetual preparation for a warmer, Mexican kind of bed. And then, of course, there's Japanese male painter Yasumasa Morimura, who is working to reproduce all of Kahlo's major paintings in faithful mirror images, albeit with his own hairy face in the place of hers. What the hell is this?

Diva Days: The Latino Film Festival celebrates the grand actresses of Mexican cinema's golden age.

It's the Clothes You may still be unaware of that fervent New World religion for which no innocents have yet been harmed known as Kahloism. "Kahloism is a religion that worships Frida Kahlo as the one true God," online Kaholism keeper Kimberly Masters explains on her website. "Kahloists have a dress code. Only incredibly sexy or very unique clothing is allowed. Kahloists are individuals who are not afraid to be themselves in a world that seems to reward conformity." With new worship comes new language, and Masters has introduced the hep term "Blue House." Because Kahlo was born and also died in Casa Azul (now a national museum), a home named for the color of its walls, Masters informs, "We use the term 'Blue House' to describe anyone who is awesome enough to either (a) have an affair with either Frida or Diego or (b) [be] able to party with Frida and the rest of the gang. ... Anyone [who] wears thick glasses and terrible clothes is not 'Blue House.' Madonna is 'Blue House.' A tremendous amount of today's models, actresses and actors are 'Blue House.' "I think," she ends archly, "you have the point by now." Yeah, it's about the clothes. Although she was perhaps more widely photographed than even self-painted, Kahlo's extreme decorative style is what remains best known about her today. Passionate about the peasant heritage of her homeland, she elaborately garbed herself in the decorative finery of the native Tehuana people. Long skirts hid her polio-ruined left leg; massive necklaces of turquoise, jade, coral and silver shielded her neck; frilly blouses adorned her bosom; and her hair was regularly dressed in braids and ribbons and flowers, even when she was hospitalized--and she was hospitalized often. Her nails were always polished--the national museum in Mexico still displays her solidifying bottles of varnish. Her lips were always rouged. And make no mistake: tweezers had been invented back then; she just chose not to use them. Now 86, Bay Area artist Pele deLappe was 14 when she first met Kahlo in 1931. Kahlo and her husband, the muralist Diego Rivera, were living for a short time in San Francisco while he painted the walls of the Pacific Stock Exchange. Freed from the strictures of a bourgeois education by an impatient father who wanted her to grow up and go to art school, deLappe spent her afternoons drawing and smoking with Kahlo, then 24. "She always wore long Mexican skirts and dresses, gorgeous-looking things, and these big, heavy necklaces made of jade beads that I absolutely adored--and very fancy earrings," deLappe remembers. DeLappe, who is well read and fiercely political, and has an extraordinarily cogent memory for dialogue, names and places, is hard-pressed to recall more. She remembers that Kahlo's English wasn't very good (she later became quite fluent in American slang), and that she met up with the couple again in New York, where Rivera was making his infamous mural at the Rockefeller Center. DeLappe washed Rivera's brushes and even posed for the work, which was destroyed before completion because the artist, a stout Communist, refused to remove Lenin's face from the painting. But what about Kahlo--her quirks, fears, pleasures, personality? "I would go shopping with Frida," deLappe says with uncharacteristic simplicity. "I remember vividly one purchase we made at Klein's on the Square. Frida and I went there and found these beautiful red suede jackets. I'd give my right arm for one now." We are, she is sternly reminded, talking about clothes again. DeLappe laughs gaily. I suddenly look down at myself. After a month of reading and thinking about Kahlo, I find that I'm wearing a long frilly skirt, my nails are painted red, I'm sporting a Day of the Dead skull necklace such as she favored and I am even wrapped in a gosh-darn rebozo. It's the Attitude Thank God for poet and novelist Kate Braverman. "Frida is a compendium of modernity, what a modern woman is," Braverman says crisply by phone from her Bay Area office. "If you only plug into her on the level of fashion, that's superficial. She was a sexual revolutionary, a political revolutionary, and her art is considered much more important [than Rivera's] now." A reverberant inner dialogue on Kahlo based on the artist's biography and work, Braverman's latest book is Incantation for Frida K., a prose poem in which she strives to translate Kahlo's images into words. "Most people, given an opportunity to respond to any phenomena, will take the most shallow and conventional aspect," she says. "That's why you have fashion being more important today than art or philosophy. In my book, the way that I explain the clothes is with the concept that Diego has that the only way to be a footnote in history is to create a media event. He seizes on the idea of [Kahlo's Tehuana] costumes to make [her] visually recognizable. In my book, he was a fashionmonger, and she dreams of being free, of a new life of never having to wear garish peasant costumes in the frigid chill of North America again. Imagine being in Detroit in those clothes! "She was not only a person of her time, but before her time," Braverman continues. "The real interest in Frida ... is that there is no aspect of the feminist movement that she does not presage. Her life was like a prophecy. She did it first. If you are just getting into Frida on a decorative level, you degrade her intellectual and artistic brilliance and her struggle to not only survive but to transcend her illness, which was ghastly."

It's the Pain Almost as well known for her suffering as for her paintings, Kahlo was first reintroduced to popular culture in the embrace of that late '70s-early '80s misguided faction known as "victim feminism." Lauded in narrow circles as a marvelous representation of female suffering --and making her first appearance on earrings and mugs--Kahlo served as an unintentional poster girl for this movement. Yet it must be admitted, we can find a creepy fascination with the tormented details of a woman possessing so many physical obstacles, who was unable to bear the children she so wanted and yet continued to display rapacious sexuality and a keen lust for all things corporeal--and who doggedly made herself into a star. "She recognized herself as being mythic when she was hit by the trolley car," says Braverman. "And as her life progressed, to live her life as a mythic character was a great ..." She pauses. "Well, it's a very dangerous way to live; I do it myself." What's it like? "It's a great rush. It's totally exhilarating. It's addictive." Indeed, Kahlo's horrific streetcar accident has the weighty stuff of addictive myth. (In her diaries, she writes that she actually had two terrible accidents: the first was the streetcar; the second, Diego Rivera.) Briefly put, the 18-year-old girl watched in slow-motion horror as a trolley hit the streetcar she was riding on, pushing a metal hand-rest in through her back and literally out through her vagina. The blast of the crash blew her clothes from her body, and she lay nude and bleeding, her spine broken thrice, with a pole protruding between her legs as a fine patina of real gold dust floated down upon her body from the fractured package of a fellow passenger. Hoping to distract her during her long recovery, her parents gave her a paint set. From this unlikely scenario, a painter--and now a film, many books and all those trivets and odd miscellany--was born. It's the Art Affixed to the underside of her bed's canopy was a mirror, and from its wavering reflection Kahlo wove her own visual language. An untrained "primitive" artist, she was later surprised to be proclaimed a surrealist by the French practitioner André Breton, whom she purportedly loathed and whose wife she purportedly seduced in a neat bit of revenge. Energetic romans à clef, her paintings symbolically depict her physical and emotional pain through recurring motifs and return unflinchingly to her own unblinking face. But were her paintings any good? Would we be watching biopics and reading nasty little Madonna stories and writing books if she hadn't been married to Diego Rivera? Depends on whom you ask. "That's just misogynistic blasphemy," Braverman hotly responds. "That's a way of attempting to trivialize woman artists, and part of the women's movement's focus has been to dig these women up and to show that they were people in their own right--and in many instances more important than the men." Milder perhaps is the response of Dr. Janet Bishop, chief curator of painting and sculpture at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. "I don't think that it's possible to discount everything that we know about her life, given how her paintings are infused with it," she says. "Her biography is very much a part of the paintings," Bishop continues, "but aside from the hype associated with the work, she is highly regarded in the art world. There's a great element of daring in the work; she revealed so much of her physical pain and her emotional pain--so much of herself--in her paintings. She put a lot out there. They're also painted in a way that's very engaging to people. She uses a combination of realism and magic realism; there's an element of reality and fantasy that comes together in a very visually compelling way." And then there's art historian Sharyn Rohlfsen Udall. "Kahlo was a very uneven painter, as most painters are," says the author of Carr, O'Keeffe, Kahlo: Places of Their Own from her Santa Fe home. "When she was expressing in very accomplished formal terms what she thought about herself and her life, portraits that she did before her technique faded later in life, such as The Nurse, Two Fridas, Love Embraces the Universe--those are unapologetically extraordinary and would stand up against any 20th-century artist today. Having said that, there are many that wouldn't. That, of course, has to do in part with the waxing and waning of her physical powers. "Her willful act of painting was part of her strategy to survive. As long as she could keep painting and hold that brush, she was alive and wasn't going to die." Indeed, when Kahlo was on her feet, she appears to have been the rare kind of person who understood that our human animal in full is exquisite. But her feet were eventually trimmed, the toes of her right foot lost to amputation. Eventually, too, that leg was taken. What is not surprising in Frida Kahlo's story is that she died soon after.

It's the Husband Why Frida Kahlo set her sights on marrying Diego Rivera, some 20 years her senior, some 200 pounds her better, a huge froglike man whose physical attractions can never be accurately represented through photographs, is not really known. Perhaps, as some have claimed, she was simply a groupie. Certainly, she presented herself with a groupie's brashness to the painter, then the most famous artist in Mexico. Based sturdily on Hayden Herrera's seminal biography of the same name, director Julie Taymor's film Frida shows the young woman, recently rehabilitated from her bed, demanding that Diego come down from his painter's scaffolding to tell her whether she should continue to paint. She pushes her first few works before him. Intrigued by the odd strength of her beauty and her canvases, he encourages and eventually seduces her. Certainly, once Diego and Frida married, they became the first-name rock stars of the Depression-to-Cold War era. Like Scott and Zelda, like John and Yoko--seeking fame, courting it and absolutely milking it, Diego and Frida knew how to work both the press and the populace and did so constantly. When Leon Trotsky was exiled from Russia, after bouncing through countries inhospitable to Communist leaders, he found himself allowed entrance into Mexico thanks to Rivera's influence. He took refuge in Kahlo's home, no less, where the windows were specially bricked to ensure Trotsky's safety. When Kahlo was in Paris, Picasso was at her side. (As a small side note to Kahlo's uncanny genius for attracting fame, the first paintings she ever sold were to the actor Edward G. Robinson, then at the height of his own celebrity.) Taymor's film centers mostly on the Communist politics of the era and on the marriage and strays very little into the particulars of Kahlo's health, which is probably a wise choice. While there's a horrible fascination to reading about it, one doesn't want to spend two hours and 10 minutes watching endless back surgeries and recuperations. It's much nicer to watch the lovely Salma Hayek tango Ashley Judd into a velvet-gowned swoon on the floor of a Bohemian flat or knocking back half a bottle of tequila in one swig. "The thing about radicals," Frida is confidentially told in the film, "is that they're dangerous, but they throw the best parties." Visually splendid, with just-fine performances, Frida remains a chick flick with few bumps on its gorgeously photographed road. Its main triumph is in Hayek's ability to bring the young Frida--a girl who was educated within a circle of a cultural elite who went on to run, or, depending on one's perspective, ruin Mexico--to rambunctious life. To keep Diego, she had to be outrageous. To keep herself from going mad, she continued to be outrageous, becoming as cavalier as he in taking lovers and aiming to squeeze every last bit of juice out of what she called "this Judas of a body." "I don't see her as a victim," Braverman says. "She had a true art form, and she was brilliant. The challenge [in writing Incantation] was to find a language that was as dynamic and alien and mysterious as her paintings. That's the voice that I found for her. She is just transcendent in her revolutionary behavior. To make such bold statements--to be an artist, a bisexual and a morphine addict--she was a jet-setter before that term existed. This is how I could understand their marriage; I had to find a way to make them equals." Few lives end well, and Kahlo's was no exception. With relentless pain, with marital betrayals, with so much juice-squeezing and so many dangerous radical parties eventually came a debilitating prescription-drug problem and the need to keep plenty of brandy on hand. Thousands attended her funeral, but only a dozen or so close friends and family were in the crematorium as her body was loaded into the fire. Briefly uplifted by the back blast from the heat, Kahlo's body reportedly rose almost to sitting position, her long hair streaming freely around her, her lips appearing to the shocked eyes of observers to be formed in a small half-smile. Her last diary entry, dated 11 days before her death, confided, "I hope the exit is joyful--and I hope never to come back." Dear, good Frida, it appears that you won't get that wish.

Send a letter to the editor about this story to letters@metronews.com. [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

|

From the November 14-20, 2002 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)