Zapped Again

By Nigey Lennon

IF A BEETHOVEN had been born in World War II America and grown up in the McCarthy era; if a potential Stravinsky had lived and worked not in Paris or New York but in Southern California's desert wasteland--what sort of men would they have turned out to be, and more importantly, what sort of music would they have written? This thought rises to haunt the listener during the nearly three hours of Frank Zappa's newly released Läther.

From beginning to end, Läther conjures up horrifying images of the crass popular culture Zappa abhorred, shining a pitiless light on the artistic dilemma that provided him with grist for his creative mill but also nearly destroyed him. In many ways, socio-cultural frisson is the leitmotif in Läther (Rykodisc), a three-CD set that distills Zappa's sociological torments into something approaching a posthumous j'accuse.

And true to Zappa's dark vision of modern corruption, even the circumstances surrounding the long-delayed release of Läther point up the evils of corporate control of the media. Originally projected as a four-LP boxed set by Zappa, the project was rejected by Zappa's then-distributor, Warner Bros. Records, in 1977, ostensibly on account of its unwieldy size and stylistic inconsistency.

Zappa, in an understandable state of high dudgeon, took to the airwaves on KWST-FM in Los Angeles and played the entire four-record set, exhorting listeners to tape it off the air. Ironically, commercial bootleg releases of the material proliferated, effectively cutting Zappa out of the profit loop.

(Rykodisc, having exhaustively issued, reissued and, in some cases, re-reissued the entire Zappa catalog, appears to have run out of unreleased material. Despite the liner notes' fervid protestations that it was an article of faith with Zappa for Läther to be released as a four-record set, much of it was originally issued piecemeal in the period 197577, so this release doesn't really qualify as the debut of an entirely new Zappa project.)

Since much of the material on Läther is making at least a second appearance here, hardcore Zappaphiles will look in vain for lost masterworks, new arrangements or even fresh mixes (with the exception of a 1993 digital punch-up of the evocative instrumental fanfare "Re-gyptian Strut," which, as it turns out, is so similar to the original that it can only be viewed as filler). But what the diehard fan base--or indeed any stalwart listener--will find is a warts-and-all musical profile of the Italian-American autodidact whose slogan was a 1920s quote from composer Edgard Varèse, "The present-day composer refuses to die!"

Fittingly, Läther is a claustrophobic, sweaty sonic examination of manipulation, obsession and control, an auto-da-fé from which no fond peccadillo (or musical genre, for that matter) emerges unscathed.

Loosely linked from track to track by resonant, highly processed male voices painfully groaning out references to bondage, fetishism and other uncontrollable urges, Läther drives forward relentlessly and, in the process, provides a kind of musical biography of its composer (though it's a safe bet he didn't intend it that way).

Make no mistake--Läther's idée fixe is control, whether that control takes the form of the calendar people unquestioningly live by, the libido that is so easily coopted by canny advertising types or the artificial re-creation of the cosmos that an orchestral composer engages in (or thinks he engages in).

This is a private hell only a Catholic could imagine, although it helps that the Catholic in question also composed "serious" music while making a living playing rock guitar.

Even more than usual, on Läther, Zappa uses a plethora of musical archetypes, from doo-wop to dissonant counterpoint. While much has been made of Zappa's audacious originality as a genre-jumping composer, and while it is true that he was formidably capable of integrating modern orchestral forms, jazz scoring, rock clichés and movie soundtrack effects into a technically dazzling pastiche, it is imperative to keep in mind that Zappa was self-taught, and the attendant evils of autodidacticism were sometimes distressingly obvious in his output.

"Serious" music cannot be practiced in a vacuum, and in a sense, the strongest impression left by Zappa's musical oeuvre is that it simultaneously reflects and comments on that sad fact.

At its worst--as in many of the quasi-orchestral Synclavier passages on his posthumous release Civilization: Phaze III--his music was dry-textured and mechanistic, redolent of the post-Schoenbergian canon lauded in academia during the late 1950s and early 1960s, when Zappa was teaching himself composition and harmony in the school library.

It is ironic, in fact, that long after musical academia had abandoned dissonant counterpoint and its allied forms, Zappa was still busily cranking out "serious" music that was almost nostalgically quaint. There are a few examples of this style on Läther, namely "Naval Aviation in Art?," spots in "Revised Music for Guitar & Low Budget Orchestra" and "Pedro's Dowry," as well as in passing on other cuts.

Zappa Wired:

An extensive list of links for Zappa web sites.

Rykodisc's full Zappa catalog.

Biography of Edgar Varese, a composer who

ZAPPA'S EXCURSIONS as a rock guitarist comprised the other, better-known pole of his musical persona. Essentially a modally oriented, blues-flavored soloist, Zappa was stronger at atmospheric texture than technical fluency. Some of that bluesy feeling comes through on "For the Young Sophisticate" on the present release. Elsewhere, the lengthy solo escapades over a one- or two-chord vamp can get rather tedious.

One can't help wondering if Zappa was slyly commenting on his own obsession with guitaristic domination of the time-space continuum. In his self-referential universe, mongoloid power chording and 20-minute exercises in feedback tolerance were equal to elaborately scored orchestral passages or to sneering commentaries on human foibles and frailties.

The solos only got longer as Zappa's career progressed, as the lyrics grew more sophomoric and the tone of the proceedings degenerated into schizophrenia. Perhaps the real value of Läther is that it serves as a fascinating document of the developing cynicism in Zappa's work.

In the end, Zappa, by calculatingly throwing Webern before swine and then reviling them for not understanding it, may have been both too intellectually disingenuous and too self-referential for his own good.

As brilliant as Läther is in making a virtue of a necessity, clumping together widely divergent musical inspirations while achieving a chilling singleness of purpose and statement, the uninitiated listener is left with a troubling question: What would an intelligent person, someone who could understand the intricacies of this music, derive from the postpubescent smirking of songs like "Broken Hearts Are for Assholes"? Why did Zappa spend nearly 30 years of hard labor underestimating and insulting the intelligence of his listeners?

The answer may be simply that Zappa was born in the wrong place and time. This keen intellect, who would have been right at home in the cafes of Montparnasse or the Manhattan of the Armory Show, came of age instead in the virulently anti-intellectual 1950s, in the Cold War milieu of Southern California's defense industry. Zappa was once quoted as saying that he created "a special art in an environment hostile to dreamers." Might that observation have indicated that he felt his outsider position as an intellectual did not allow him the luxury of dreaming?

Whatever the answer, it is evident from listening to Zappa's work in its entirety that although the modern-day composer refused to die, there was nonetheless a very cramped and emotionally closed-off feeling to much of his output. In his work we hear the struggles of a soul imprisoned in a private purgatory, unable to connect with the common ground of humanity, and humanism, that great art (or music) both nurtures and propagates.

The agonized soundscape of Läther reflects these struggles in a way that is as painful to listen to as it is saddening to contemplate.

[ Metro | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

This page was designed and created by the Boulevards team.

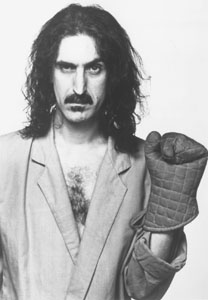

Too Hot to Handle: It took two decades for Frank Zappa's "Läther" to be released in its entirety.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

influenced Zappa.![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

Nigey Lennon, a composer/guitarist and writer, is the author of Being Frank: My Time With Frank Zappa (California Classics Books).

From the November 14-20, 1996 issue of Metro

Copyright © 1996 Metro Publishing, Inc.

![[Metroactive Music]](/music/gifs/music468.gif)