![[Metroactive Books]](/books/gifs/books468.gif)

[ Books Index | Silicon Valley | Metroactive Home | Archives ]

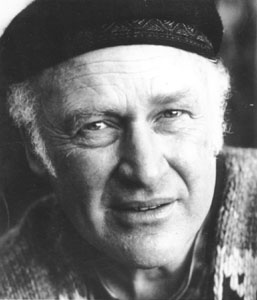

Ken Kesey, 1935-2001.

Ken Kesey, 1935-2001.

Nest Stop Ken Kesey's wild ride took many twists and turns in and around the valley Ken Kesey lived on a dairy farm in Oregon, but the Santa Clara Valley and its environs was his stage for four decades. He drew inspiration from Stanford University, Menlo Park Veterans Hospital, Santa Cruz's Hip Pocket bookstore, and visits to the valley homes of friends Neal Cassady and Candace Lambrecht. In 1993 he left an impression on the staff of Metro when he pulled up in the 1990s version of the "Further" bus, etched his name on a wood column and yelled loud enough to be heard across the entire first floor of the building, "Okay, everybody on the bus! You are either on the bus, or you're off the bus." Staffers piled out of all departments and scrambled onto the squeaky old school bus, up the ladder onto the roof above. The vehicle was wired for sound, and Kesey provided commentary through a microphone on a headset. As he headed up San Jose's South First Street, the reactions to the psychedelic bus ambling up the heart of San Jose's squeaky-clean redeveloped downtown were a sight to behold. Lawyers, dealmakers and homeless crazies stopped dead in their tracks and stared in disbelief. Kesey turned left at Santa Clara Street and circled the arena, calling it "the largest Airstream trailer in the world." On the box office side, Kesey spotted a militarylike formation of palm trees, a signature of the tightly wound redevelopment look of the 1990s and said, "Watch this." With a flourish, he thrust the his open hand out the bus window toward the columns of palms and yelled, "Stay!" It was a classic Kesey non sequitur in the theater of the absurd, and one that made perfect sense amid architecture every bit as repressed and artificially controlled as the social world he attacked in the 1960s through his novels, performance art and pioneering multimedia experiments. While they are sometimes taken for granted today as quaint and iconoclastic, America's popular culture owes a debt to Kesey and his prank mates, who introduced a distinctly Northern California cocktail of improvisational music, psychedelic drugs, road culture, recording technology and nonlinear narrative to the public consciousness. This week, in commemoration of Kesey's life and local adventures, we asked two San Joseans to share some recollections. John Cassady, whose father Neal drove the original Further bus cross-country and who himself joined Kesey for a bus tour of England in 1999, penned this personal reflection. And San Jose State University English professor Alan Soldofsky, who directs the university's new Graduate Creative Writing program, remembers Kesey's infamous 1993 visit to the halls of local academia. --Dan Pulcrano Farewell to the Chief The long, strange trip came to an end for Ken Elton Kesey at 3:45am, Saturday, Nov. 10, 2001, after 66 years and a few hundred lifetimes on this planet. Ken was a great friend to my father, Neal Cassady, and almost a second father to me after Neal died in 1968, when I was 16 years old. Kesey was one of the kindest and wisest men I've ever known, and he was one of my biggest heroes and mentors starting soon after he met Neal in the early '60s, a feeling which continues in me to this day. Neal always wanted to be a provider to his family, and little did he know that much of that provision would be accomplished posthumously through doors that were opened to me because of his famous friends like Kesey and the Grateful Dead. Much to the worry of my mother, Kesey and Neal would come collect my sister and me at Saratoga High School, giving the authorities some song and dance about dentist appointments or whatever, and they'd whisk us away to see the Dead play at a Mountain View high school's prom dance, just after they changed their name from the Warlocks. After Neal's death, Kesey would go out of his way to look us up when he was in the Bay Area, and he showed up unannounced at my wedding in November of 1975 on his way back from Egypt, while writing a piece for Rolling Stone. That was one heck of a party. I still have pictures of him holding my then-3-month-old son and beaming like a proud godfather. Another warm memory was backstage at a Dead show in Eugene, Ore., when Kesey's fellow prankster Zonker ceremoniously presented me with one of two railroad spikes that the Dead's roadie Ramrod, while on a sacred pilgrimage, had extracted from the tracks where Neal died in Mexico. And again when Kesey and Ken Babbs bequeathed Neal's black-and-white striped shirt to me that he had worn on the bus trip in 1964, this time during a show we did at the Fillmore in 1997 before bringing the bus to Cleveland, where it was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame. Ken called and asked if I would drive "Further" into Ohio "because Neal can't make it this trip." Although veteran Prankster driver and mechanic George Walker wound up at the wheel, Kesey's heart was in the right place. That road trip was surpassed only by the four-week tour of the U.K. the next year, sponsored by London's Channel Four studios. Traveling with Ken in close quarters for that long really made for a lasting bond between us, and he was at his peak as a performer. I last saw him as we said our good-byes at SFO after that incredible journey, and I was sad to have not been able to do so again before last Saturday. Ken Kesey was a great teacher and a beautiful soul. He will be missed by all that were touched by his magic. --John Allen Cassady Sometimes a Great Spectacle After Ken Kesey's performance at San Jose State University on Sept. 23, 1993, I thought I might be fired from my job directing SJSU's Center for Literary Arts. Kesey had been invited to read as part of the university's Major Authors Series. He was touring on behalf of his long awaited novel Sailor's Song, his first novel in 25 years. With much fanfare, Kesey's publicist at Viking Press told me that Kesey, accompanied by a few veteran "Pranksters," would drive the reincarnated version of their psychedelic school bus to San Jose if we could park the bus on the campus. Far out, I thought. When Kesey finally steered the new edition of his bus "Further" onto the plaza behind Tower Hall, it was clear he was planning to do more than read. I repeatedly told the esteemed author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest that I was concerned about the reaction from the university's officialdom, but he told me not to worry. And he would not be swayed. Kesey had always been a showman, but I knew at heart he was a serious writer. He left Oregon in 1959 with a fellowship to the prestigious Stanford Graduate Writing Program. In 1962, while living on Palo Alto's Perry Lane and taking classes at Stanford, Kesey published Cuckoo's Nest and soon thereafter sold the movie rights. He finished Sometimes a Great Notion in 1964 at the cabin in La Honda he purchased with Cuckoo's Nest funds. After having been busted for marijuana in 1966, he seemed to have settled down. He had been living quietly on his farm in Spring Hill, Oregon, raising his four children. (He sold his legendary log house in the redwoods in the summer of 1997.) Kesey had become a pillar of the community, teaching an occasional fiction-writing seminar at the University of Oregon, coaching wrestling at the local high school, serving on the PTA. But I feared that university officials had an entirely different picture of him. They would be worried about the side of his personality that perpetually challenged authority, that instigated the notorious parties and pranks that Tom Wolfe committed to legend in The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. Knowing not what to expect, I sat nervously that September night in 1993 in the front row of Morris Dailey, next to the Dean of Humanities and the Arts, waiting for Ken Kesey and his band of Merry Pranksters to take the stage. As soon as the house lights came down, a streaker rushed to the edge of the stage and into the arms of waiting university police. Oh, no, I thought, here we go. Kesey came on in a top hat, a combination Wizard of Oz and ringmaster cum Mel Brooks. The audience roared. The production was supposed to be a rock musical, a metaphysical update of the Frank Baum classic, replete with magic tricks and special effects. But it was the last special effect that left me most tense, a mock-sword fight with acetylene torches, the flames uncomfortably close to the old velvet draperies hanging above the sides of the stage. As the smoke in the front of the auditorium cleared, I glanced at the dean. He did not look pleased. When I came in the next morning, the dean made it clear that he wanted Kesey to be "under control" when the author next spoke to students in the afternoon. I met Kesey for coffee before he came to campus for his appearance, explaining to him as tactfully as I could that the previous night's performance had not gone over well. He said he would make it up to me. At 12:30pm I introduced Kesey to an overflow audience in the refurbished auditorium in Washington Square Hall. There were no special effects, other than Kesey's own text. He read excerpts from Sailor's Song, and answered questions politely and thoughtfully. How strangely comforting it is to recall Kesey's words in these new, scarier times. He understood that art could achieve startling effects if it was raised to the level of spectacle. His great, early novels were about raising complacent, pre-1960s American life to just such a level the same way he raised to the level of spectacle his own public persona. His writings changed our cultural narrative. His work demanded that we be participants in our lives not spectators, as he demanded of himself. How astonishing it is that we had a Ken Kesey amongst us, and that we can reinhabit his words, even if we are unsure what to do once we've consulted them. --Alan Soldofsky [ Silicon Valley | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 15-21, 2001 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2001 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.