![[Metroactive Features]](/features/gifs/feat468.gif)

[ Features Index | San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

Photograph by George Sakkestad Wheeeee! Hours: Ed Wank of radio station 104.9 FM's morning program, the Wank and O'Brien Show, goes into the office at 4am to prepare the 'morning drive' time, which has gotten earlier as commute times and distances have grown longer. The Night Shift As the roadways grow more crowded and the workday creeps ever longer, more and more people are living and working after dark By Dara Colwell I AM WALKING DOWN Santa Clara Street at 11:30pm, on a moonlit fall night. Two teenage couples grope publicly at a bus stop, pressed against a glossy Clamato Vampiro sign, while across the street, in front of Albertson's, a homeless man, groggy with the hour, barters for a menthol cigarette. The fluorescent lights of an open Laundromat hum, casting the gum-saturated sidewalk in grayish green light illuminating a small child whose parents have kept him up past his bedtime. The little boy, hand clasped in his mother's, parrots the blinking crosswalk signal as he walks. "Hello. Hello. Hello. Hello," he repeats with each tiny step. From a nearby curbside roost, two mentally ill stragglers clear their throats at operatic levels, shrieking like feral cats, their foreign cacophony lingering in the night air. The wind kicks leaves into the path of an oncoming bus, through shadowy alleys between buildings and, finally, against the wall supporting a motionless gas station attendant, who sleeps fitfully, his arms flattened against the office window.

Rescue 911: Paramedic Nikki Charvez says she's been a night owl for as long as she can remember and thrives on the unorthodox things that occur after dark.

ON THE OTHER SIDE OF TOWN, the Beastie Boys are bringing on the bass in Nikki Charvez's ambulance. Charvez, a wickedly sharp paramedic with purple hair, asks her driver, Josh Padron, to lower the volume. The patient, a frail 74-year-old Chinese woman, broke her hip and was dragged in from the front lawn by her husband. The pain dances across her elegant, stoic features, but she doesn't speak English. Her daughter, confused and worried, translates as Charvez takes notes on the hand of her plastic glove. The siren goes on with its urgent, repetitive cry. Charvez operates on adrenaline, wit, hot chocolate and insatiable curiosity. She has always been a child of the night, struggling through mornings, intrigued by the morbid, the alternative and the camaraderie that dusk invites. "Night people, we're odd ducks--definitely a different breed," she says. "Humans are not nocturnal creatures; we have to train our bodies against the nature of things." Like any paramedic, she has dealt with dozens of human maladies: cancer, HIV, heroin overdoses, suicides--both successful and unsuccessful. The job is physically and emotionally demanding. "Terrible things happen to really good people. As morbid as it is, we say, 'At 3 or 4 in the morning, people wake up dead,'" she says. "There has to be someone out there to take care of them." The next call of the night is a little closer to death. A 78-year-old man, the right side of his face drooping and paralyzed by a mild stroke, lies face up in his neighbor's home. Surrounded by Indonesian paintings and plush cream-colored sofas, the firefighters and paramedic crew--six people--gingerly lift the man, who appears to the onlooker helplessly infantile. A calico cat looks on nonplussed from the top of the stairs. The siren roars again. "BP 130 over 80. Grips are equal, pupils pearl, slurred speech, occasional PVC. Patient has a history of TIAs [transient ischemic attacks--or mini stroke]," Charvez, scribbling on her glove, yells up to Padron. "What's the ETA?" "Three to five," he shouts back. "Sir, I know it looks like we're making a big fuss over you," Charvez jokes. There's silence as the man squeezes his hands into fists, checking to see if the paralysis has spread.

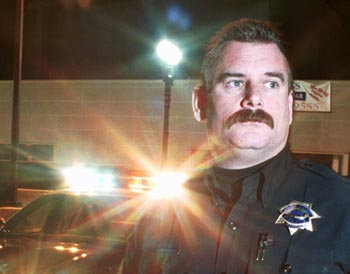

Dark Side: Sgt. Jim Overstreet has worked nights for 20 years and likes the fact that more serious calls often come in at night.

THE LATE NIGHT is a time for the unorthodox--when a car can cruise from the Alum Rock exit off 101 straight to Meridian in less than five minutes. In some places sound stops, the silence descends, and pigeons, raccoons and cats hold court in the middle of the road, undisturbed. In the mega-Safeway off Meridian, a handful of shoppers, some still in business suits, stroll through the empty aisles, casually thumbing boxes of macaroni and cheese. A young man, Post-It note stuck to his index finger and a cell phone cradled against his ear, OKs his 10-item shopping list with his girlfriend, while a strain of a Phil Collins song floats through the store. On Lincoln Avenue in Willow Glen, a police car is parked at the curb with an officer just starting his all-night shift. Sergeant Jim Overstreet, working nights for the last 20 years, is a vigilant observer of the goings-on after dark. Last October there were 5,320 crimes reported in San Jose. One murder, 29 strong-arm robberies, 100 sexual misdemeanors, 348 narcotics felonies, and 536 occasions of disturbing the peace. Most of these happened at night. Sgt. Overstreet swings energetically into Starbucks, past a collection of bored teens, for a single latte. He tells me he has always been a night owl. It suits his wife, who is a lawyer, and their three kids, who have been raised knowing that their dad is seldom, if ever, going to be around for bedtime stories. "The graveyard shift is the reason why I became a police officer," he says. "At 2am, people don't call you for petty things--they're sleeping. So when they call, they really need the police. At night, you have to be more alert." Sgt. Overstreet is a robust man whose bushy mustache seems to spike whenever his finely tuned eyes scan the night's muted landscape. He drives along the Monterey Highway, eyeing the city's remote motels and parking lots. He says that the isolated location offers a low-key alternative for making drug deals, staging occasional shootouts and hiding stolen vehicles. A couple of motel doors are propped open, revealing beds, bare feet, flickering televisions and disgruntled-looking women. Nothing stirs as Overstreet flashes his light and moves on. Circling back toward downtown, the Sergeant spots a homeless woman pushing her heaping shopping cart down the middle of the street. The woman, appearing to be in her 40s, half pushes and half sways as she walks, but pays no attention to the patrol car tailing behind her. Overstreet's voice roughens. "What the hell are you doing? Get that thing out of the street--you're going to get run over!" he barks. The woman, unfazed, eventually responds by slowing down her crooked pace. "OK, man," she slurs, looking over her shoulder. "All right," she trails off, shuffling with her load and moving toward the left-hand side of the road, into the oncoming traffic lane where, fortunately, no one is coming.

Nocturnal Admission: The human body does not digest food well in the night, even if lunch is at 3am. Hard Day's Nights: Under pressure to put in long hours, even day workers are short on sleep.

BURNOUT, FATIGUE, physiological stress, smoldering midnight oil, Three Mile Island, Exxon Valdez--accidents that happen at night. Truck and train drivers are 15 times more likely to crash at dawn than at dusk; fatigue-related accidents in the United States cost the economy as much as $1.5 billion a year, airplane crashes and plant explosions another $5 billion annually, and $6 billion bleeds into health care costs. Sixty-eight percent of night-shift workers report sleeping problems, 53 percent don't sleep regularly and 41 percent admit to dozing off at the wheel. At San Jose Medical Center, the emergency room's Meditech board tonight displays "ETOH" for ethanol alcohol, alongside other complaints: vomiting, chest pain, constipation and fever. Drinking accounts for a large percentage of each night's intake, says Eugene Dong, a good-humored nurse with yellow-tinged wire frame glasses. A few minutes later, almost like clockwork, a man is rushed in by the paramedics--a collision. The driver, wearing torn black jeans exposing his legs, had been drinking, and not wearing a seat belt. "And he was so close to getting home," Dong says, with that peculiar, refreshing medical humor. Within an hour, the driver is sober and walking, his X-rays and vitals checked out. "What kills you is what you don't see, what you might miss," Dong says, turning to speak with a colleague. In another room, a woman diabetic waits to be released. She'd been drinking at a bar when she suddenly collapsed. AT DENNY'S ON South First Street, the night shift is taking its "lunch break." Here, the Moon shines over MyHammy, eggs are slammed, potatoes scrammed, and meat, in its most generic sense, is covered 'n' smothered then smothered again, 24 hours a day, every day. Barbara Salazar, a perky waitress in her 40s, breezes over to a Hispanic couple and serves the lady, a dramatic-looking woman with a pronounced, sensual pout, a piece of Oreo cheesecake. As Salazar leaves, the woman leans in toward her companion. "Entonces, estoy feliz," she sighs. Nearby, a group of loud teens wrestle over the menu. "Dude, did we order yet, dude?" one guy asks, pounding the table. Salazar started working the night shift two months ago when her father was diagnosed with hypersensitivity numinitus, an inflammation of the lungs due to environmental allergies. Her sister guards him at night, when he sleeps with a breathing machine, and Salazar takes over during the day. She worked the normal 9 to 5 before but finds this new nighttime world intriguing. "I meet a lot of interesting people, especially the crowd from the nightclubs. They are always in a positive mood," she says. But she feels too old to continue fighting the internal clock. She wants to stick with the job until her father improves. "Once I lay down, it's hard to go to sleep, my mind is still going. I'm curious what other people are doing, so I get up," she says. "But everything's the opposite. When I walk in the door, [my family is] eating breakfast; when I wake up from a nap, they're eating again. I feel like I'm eating around the clock, 24 hours a day."

Nocturnal Animals: Gordon Biersch beermaker Peter Kruse likes working with yeast in the wee hours. 'You can never completely control yeast,' he says. 'You're dealing with an animal.'

PETER KRUSE, a lean brewer with his blue jeans tucked into black rubber boots, cooks silos of beer until dawn. Pilsner, Golden Export, Marzen, Blonde Bock--get brewed by Kruse in bulk at Gordon Biersch's bottling plant on Taylor and Ninth streets. "You can never completely control yeast," he says with visible appreciation. "It's an unknown element; you're dealing with an animal." Kruse looks like he's stradding one as he transfers the fresh brew from a three-story cylindrical kettle, clad in corrugated steel, into a storage tank. He clasps a thick hose, as heavy and unruly as a boa constrictor, between his legs and aims its mouth toward the floor. Eventually, beer gushes out and Kruse attaches its base to the new tank's inlet valve, and then the beer swoops up into the tank's stainless belly. It takes four brews, at seven hours cooking time each, to fill one mammoth tank. The brew sits there for 40 days lagering, or being stored--an alcoholic Noah's ark. It's 12:30am and Kruse is wide-awake, strolling past yeast propagators and kettles filled with wort--a warm, filtered water--and grist mash to check his concoction. The room is suffused with the earthy, comforting aroma of yeast. "What's the cell count, do we know?" he asks his colleague, Jeff Barboni. The two work alone in the 114,000-square-foot facility, which dwarfs everything in sight. Together, the company's brewers create 75,000 barrels of beer a year, which is sucked into bottles and kegs and distributed throughout California, Hawaii, Nevada and Arizona. Kruse never considered himself a night person, but the opportunity was there and he took it. "You don't know what it's like until you do it," he says of the night shift. "The effects are cumulative. It changes your life, your social life, drastically. I don't think I've had lunch with anyone for over a year; when I get out of work, nothing is open--there's a lot of alone time. We ask ourselves every day," he says looking over at Barboni, "how much longer can we do this? But if this is what you want to do, it doesn't matter when you do it. We're making beer, that's a good thing."

Photograph by George Sakkestad

AT HOUSE OF BAGELS in Campbell at 3am, 911 plain, 416 sesame, 413 raisin, 369 blueberry 215 wheat, 57 jalapeño and 24 sugar bagels sit, warm and doughy, ready to be bagged and dropped off for customers throughout Silicon Valley. Driver Steve Heilig, with a touch of sleepy hysteria, rubs his head. Today is eBay's weekly $1,000 order on top of his usual downtown run--making his total 21 drop-offs--and it's already raining hard. In 1988, Americans were eating an average of one bagel a month; in 1993, the average doubled to one bagel every two weeks, and within the past decade bagel consumption has increased 150 percent. The bagel's biggest demographic: adults between the ages of 25 and 64 with incomes of $40,000 or more. Heilig, who has the look of a scratchy, aged windsurfer, fine blond hair tied in a loose ponytail, got his first taste of California at a hair convention in the mid-1980s. He moved from Illinois to San Diego, then worked his way up the coast, clipping hair from Los Angeles to Santa Rosa. Clipping ladies' hair, that is, often in their homes. He still makes hair house calls. "My customers are mothers with children who can't get to the salon, or single women who like to be waited on," he says, smiling an obvious smile. "I've got some house call stories that would curl your hair!" Heilig starts loading his van, heavy metal music and rain drumming in time to his awkward shuffling. Once the van is loaded, he heads to his first drop-off, Home Sleep, a company that treats people who suffer from insomnia and other sleep disorders. The irony isn't lost on Heilig. "I should be home asleep!" he says. "I've always been a night owl, but getting up for 3 in the morning, I'm exhausted all the time. I can't remember the last time I had eight hours sleep. I have four different alarm clocks set to go off at one-minute intervals in each corner of my bedroom. They sound like ambulances. My roommates say it's like living with a fireman!" Heilig jolts through town, from the Elks Club to the Fairmont Hotel to San Jose State University's coffee store chain, Jazzland. It's just past 6am and traffic is beginning to build on the streets. "That's my biggest reward of the day," he says, motioning toward cars waiting for the light to turn green, "when I go home and everyone's sitting in traffic, driving like lemmings to the sea, and I'm done."

IT'S TRUE THAT the roads feel empty in the middle of the night, particularly by comparison to daylight hours. During the past 20 years, the number of cars on the road has increased at a steeper rate than any other demographic indicator--one and a half times that of the total population. A typical household traveled 4,000 miles more in 1995 than it did in 1990; 233,000 cars pass daily between the Mountain View and Shoreline Boulevard exits on Highway 101. For DJs Ed Wank and Dave O'Brien, that's reason enough to roll into work by 4am. Because people in Silicon Valley are rising earlier and earlier to beat traffic, Wank and O'Brien, who host the morning show on 104.9-FM, have got to be there, happy and alert, for them to listen to while they are driving. "The a.m. drive is from 5 to 10. In most places, it's 6 to 10," Wank says. Both have an easy 20-to-30-minute commute. Both DJs worked with each other in Indiana before coming to San Jose. O'Brien, who looks boyishly sporty, hailed from a commercial college radio station in Virginia, and Wank, who has the eclectic-looking, confident demeanor of a comic, got his start in Syracuse, N.Y., doing stand-up. Wank plugs in the morning's programming as his partner flips through a fresh stack of newspapers, searching for human-interest stories to pepper the morning news. When the show--which reaches 30,000 morning listeners and 225,000 at less ungodly hours--begins, both hosts are energetic, happy, morning people, the enthusiastic type that most insomniacs would shirk. As the music runs--an '80s array ranging from Fine Young Cannibals, Edie Brickell and the New Bohemians, and Prince to the Psychedelic Furs--both hosts pick up speed. They're awake. O'Brien lopes through a number of news items: computer glitches, airline traffic, game three of the World Series, the kidnapping of a female jogger in Los Altos. "David Hasselhoff is suing a man who said Baywatch was his idea. The man originally settled for $200,000," he says, later continuing, "I'm amazed someone could steal the idea for Baywatch." "I think any guy in America could say that," Wank interjects. "Like, 'Hey! I thought of that when I was 12!'" IT'S NOW 7AM--time for the traffic report. Another typical day: two big rigs and a pickup truck have overturned on Highway 101. "Avoid it if you can," the reporter says, her voice animated. It is no longer night, no longer the unorthodox hours, the wee hours, when darkness, sleep, drunkenness, fuzzy thinking, mystery and solitude hold sway. It is now time for breakfast, for things traditional and routine, time for school buses and scrambled eggs, email and morning presentations. Time for the offbeat--hopefully--to go to sleep. [ San Jose | Metroactive Central | Archives ]

|

From the November 16-22, 2000 issue of Metro, Silicon Valley's Weekly Newspaper.

Copyright © 2000 Metro Publishing Inc. Metroactive is affiliated with the Boulevards Network.

For more information about the San Jose/Silicon Valley area, visit sanjose.com.

![[line]](/gifs/line.gif)

The Night Kitchen: Steve Heilig works the night shift bagging and delivering bagels to House of Bagels' corporate clients in time for morning staff meetings.

The Night Kitchen: Steve Heilig works the night shift bagging and delivering bagels to House of Bagels' corporate clients in time for morning staff meetings.